“Which English translation of Notes from Underground should I read?”

In his introduction to the Ginsburg translation published by Bantam, Donald Fanger says, “Notes from Underground has attracted many labels. Some have seen it as its author’s defense of individualism, others as a case history of neurosis, a work of high comedy, or a specimen of modern tragedy. Dostoyevsky’s text makes each of these interpretations plausible, but finally escapes them all. The best approach may be to put aside the question of what it means in order to consider what it is and how it conveys meaning. These ‘notes’ are a performance, part tirade, part memoir, by a nameless personage who claims to be writing for himself alone but who consistently manipulates the reader—of whom he is morbidly aware—to the point where there seems to be no judgment the reader can make which the writer has not already made himself…. Abrasive, unlovely, brilliant, insinuating, he commands our attention as a contemporary, posing problems as absorbing, elusive and endless as his Notes.”

This novella was serialized in Russian in 1864. It’s often published with one or more other short works by Dostoevsky in a single volume. (Publishing multiple complete works together is, like, the extreme opposite of serialization, where only one part of a single work is published at a time!)

So which translation should you read? There are over a dozen to choose from…

“Notes from Underground In English by Ira Nadel”

This 52-page PDF compares a few passages, outlines the history of the translation of this novel, and describes all the translations, focusing on the content of the supplementary materials in each edition.

Notes from Underground: Translations in English

There have been 17 English translations, and almost all of them are in print:

-

- 1913 – C. J. Hogarth

- 1918 – Constance Garnett

- 1955 – David Magarshack

- 1960 – Constance Garnett revised by Ralph E. Matlaw

- 1961 – Andrew R. MacAndrew (Signet)

- 1969 – Serge Shishkoff

- 1972 – Jessie Coulson (Penguin)

- 1974 – Mirra Ginsburg (Bantam)

- 1989 – Michael R. Katz (Norton)

- 1991 – Jane Kentish (Oxford)

- 1993 – Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky (Everyman, Vintage)

- 2006 – Hugh Aplin (Alma)

- 2009 – Ronald Wilks (Penguin)

- 2009 – Boris Jakim

- 2010 – Kyril Zinovieff and Jenny Hughes (Alma)

- 2012 – Natasha Randall

- 2014 – Kirsten Lodge

Notes from Underground: Why are there slightly different titles?

Some editions are called “Notes from Underground” and others are called “Notes from the Underground.” Russian doesn’t use articles like a/an/the.

In addition, the intended connotation is apparently difficult to convey in English.

From the Afterward by Andrew R. MacAndrew:

“[The] Russian title would be more accurately if less dramatically translated as Notes from a Hole in the Floor, i.e., from a mousehole.”

From the Translator’s note by Mirra Ginsburg:

“In addition to its metaphorical sense, which coincides with the English ‘underground,’ podpol’ye means, literally, the space ‘under the floor.’ Notes from Underground then, does not convey the full connotations of the Russian title—impossible to reproduce in English.”

“Notes from Underground In English” by Ira Nadel

“[In their introduction, Zinovieff and Hughes] state that the title of Notes is difficult to translate and has been mistranslated in English for over ninety years since Constance Garnett called it Notes from the Underground in 1918. The Russian means something else: literally, ‘Notes from Under the Floorboards.’ Nevertheless, the translators decide to keep the old title because of convention and recognition ‘but it is wrong’ (xi). But does an exact translation of the title matter they ask? Yes, because the connotations of ‘underground’ suggest something criminal, conspiratorial, revolutionary, not the space under the floorboards where rodents live and, according to folk legend, the space of devils and demons. The narrator of Notes is in fact ‘a little mouse ensconced under the floorboards of his St. Petersburg flat’ (xi)…. The ‘Translators’ Note’ begins again with the question of the title, citing Nabokov who suggested ‘Under the Floor.’ Others have suggested ‘Notes from the Cellar’ but such spaces are habitable by humans. Dostoevsky implies something less appealing to suggest space only for mice or demons.”

Notes from Underground: Why it’s high on the scale of untranslatability

From the Translator’s note by Mirra Ginsburg:

“Of all Russian writers, Dostoyevsky is probably one of the most resistant to translation into English. The difficulty stems not only from the character of Russian as compared with English, but from the manner in which Dostoyevsky used language, from the essential tenor of his writing, and the area of human experience he was concerned with.”

I don’t think anybody considers any of Dostoevsky’s work easy to translate, but for what it’s worth, Katz says this story was particularly difficult:

From “A Note on the Translation” by Michael R. Katz:

“[Notes from Underground]” remains one of the most challenging texts to translate in all of Russian literature, beginning with the first three lines of the work…. The style of the work makes it very difficult to translate. Its unusual syntax, its broken speech, its irony and sarcasm, and its passionate polemic with an implied interlocutor test the translator’s skills and patience.”

Notes from Underground: Translation comparison

Extracts have been included wherever possible so that you can compare how the different translations sound.

Best translation of Notes from Underground: TL;DR

If you just want a quick-and-dirty recommendation, jump to the conclusion.

“How is the author’s name supposed to be spelled?”

Well, he was Russian, and Russians use the Cyrillic alphabet, not the Latin/Roman alphabet. The author’s name looks like this in Cyrillic:

![]()

There are multiple “English” transliterations:

- Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky

- Fyodor Mikhaylovich Dostoyevsky

- Fyódor Mikháylovich Dostoyévskiy

- etc.

Who was C.J. Hogarth?

Charles James Hogarth was a British translator. He translated works by Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Gogol, Turgenev, and other Russian authors.

“Notes from Underground In English by Ira Nadel”

“Charles James Hogarth (1869 –1945) educated at Charterhouse, was a translator who made an early career publishing editions of Gogol’s Dead Souls, Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons, Gorky’s Through Russia and Goncharov’s Oblomov, plus Dostoevsky’s The Gambler, Poor Folk and Notes. He was sometimes criticized for his incomplete knowledge of Russian but rich imagination, although one critic claimed that he had provided Gogol with such an elaborate style as to make him unrecognizable.”

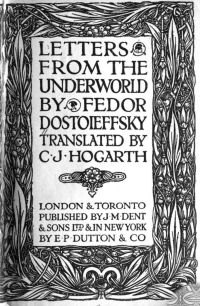

About the Hogarth translation of Notes from Underground

Title of book: Letters from the Underworld

Contains: “Letters from the Underworld”, “The Gentle Maiden”, and “The Landlady”

This was the first translation of all three stories into English.

Original publication: London & New York: J. M. Dent / E. P. Dutton. Author’s name spelled as Fedor Dostoieffsky.

Also includes a brief introduction by C.J. Hogarth

This translation uses British spelling.

This translation is in the public domain and there are scans of multiple Everyman’s Library reprint editions available online at Hathi Trust as well as Google Books (see below). I don’t know of a good transcription.

“Notes from Underground In English by Ira Nadel”

“In this late Victorian, moralistic introduction to Dostoevsky that omits any biographical or linguistic detail, the focus is on exposure to immoral behavior teaching

the reader right choices.”

Get the Hogarth translation of Notes from Underground

This edition is out of print. You may be able to find a second-hand copy.

The book is in the public domain, and scans are available online free (see below).

Extract from the Hogarth translation of Notes from Underground

First ~500 words of Chapter 1 (from Archive.org):

I am ill; I am full of spleen and repellent. I conceive there to be something wrong with my liver, for I cannot even think for the aching of my head. Yet what my complaint is I do not know. Medicine I cannot, I never could, take, although for medicine and doctors I have much reverence. Also, I am extremely superstitious: which, it may be, is why I cherish such a respect for the medical profession. I am well-educated, and therefore might have risen superior to such fancies, yet of them I am full to the core.

Also, I have no real desire to be cured of my ill-humour. I suppose you cannot understand this? No, I thought not; but I can understand it, although it would puzzle me to tell you exactly whom I am vexed with. I only know that I do not choose to offend the doctors by telling them that I am unable to accept their treatment. Also, I know — better than any one else can do — that I alone am my worst enemy, and that I am my own worst enemy far more than I am anyone else’s. However, if I am not to be cured, so much the worse for me and my evil passions. If my liver is out of order, so much the worse for my liver.

I have been living like this for a long while now — for fully twenty years. I am forty years old, and, in my day, have been a civil servant. But I am a civil servant no longer. Moreover, I was a bad civil servant at that. I used to offend every one, and to take pleasure in doing so. Yet never once did I accept a bribe, though it would have been easy enough for me to have feathered my nest in that way. This may seem to you a poor sort of a witticism, yet I will not erase it. I had written it down in the belief that it would wear rather a clever air when indited, yet I will not — no, not even now, when I see that I was but playing the buffoon — alter the mot by a single iota.

Whenever people approached my office table to ask for information, or what not, I used to grind my teeth at them, and invariably to feel pleased when I had offended their dignity. I seldom failed in my aim. Men, for the most part, are timid creatures — and we all of us know the sort of men favour-seekers are. Of such dolts there was one in particular — an officer — whom I could not bear, for he refused to defer to me at all, and always kicked up a most disgusting clatter with his sword. For a year and a half we joined battle over that sword; but it was I who won the victory, I who caused him to cease clattering his precious weapon. All this happened during my early manhood.

Get the Everyman's Library Hogarth translation of Letters from the Underworld

Also contains "The Gentle Maiden" and "The Landlady".

Available as an ebook.

Who was Constance Garnett?

Constance Garnett was a groundbreaking Edwardian translator of many works from Russian into English, including Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, Brothers Karamazov, The Idiot, and The Possessed (Demons), and Tolstoy’s War and Peace and Anna Karenina.

Some critics, favoring, notably, Pevear and Volokhonsky, believe Garnett’s translations are out of date, inaccurate, and obsolete, while others revere them as classics. Your mileage may vary.

“Notes from Underground In English by Ira Nadel”

“One must also consider the status of the translator when evaluating the English editions. Garnett, for example, between 1892 and the mid-1920s, translated over seventy volumes of Russian literature. She was also the wife of the well-known critic and editor Edward Garnett. Conrad, Woolf and others praised her work.”

About the Garnett translation of Notes from Underground

Title of book: White Nights and Other Stories by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Contains: “White Nights”, “Notes from Underground”, “A Faint Heart”, “A Christmas Tree and a Wedding”, “Polzunkov”, “A Little Hero”, and “Mr. Prohartchin”

Garnett’s translation of Notes from Underground is in the public domain, and there are many reprints. (Depending on the publisher, Garnett may or may not be explicitly credited; other stories may or may not be included; Garnett’s British spelling may or may not be Americanized.)

Moreover, there are updated versions that seek to remedy some of the original translation’s most obvious shortcomings. In particular, see below for information about the 1960 Garnett and Matlaw edition.

“Notes from Underground In English by Ira Nadel”

“[L]ater readers, notably Nabokov and Brodsky, criticized her work complaining that her translations were too demure and Victorian. When she did not understand

a word or phase, she omitted it.”

Extract from the Garnett translation of Notes from Underground

First ~500 words of Chapter 1 (from Standard Ebooks):

I am a sick man. … I am a spiteful man. I am an unattractive man. I believe my liver is diseased. However, I know nothing at all about my disease, and do not know for certain what ails me. I don’t consult a doctor for it, and never have, though I have a respect for medicine and doctors. Besides, I am extremely superstitious, sufficiently so to respect medicine, anyway (I am well-educated enough not to be superstitious, but I am superstitious). No, I refuse to consult a doctor from spite. That you probably will not understand. Well, I understand it, though. Of course, I can’t explain who it is precisely that I am mortifying in this case by my spite: I am perfectly well aware that I cannot “pay out” the doctors by not consulting them; I know better than anyone that by all this I am only injuring myself and no one else. But still, if I don’t consult a doctor it is from spite. My liver is bad, well—let it get worse!

I have been going on like that for a long time—twenty years. Now I am forty. I used to be in the government service, but am no longer. I was a spiteful official. I was rude and took pleasure in being so. I did not take bribes, you see, so I was bound to find a recompense in that, at least. (A poor jest, but I will not scratch it out. I wrote it thinking it would sound very witty; but now that I have seen myself that I only wanted to show off in a despicable way, I will not scratch it out on purpose!)

When petitioners used to come for information to the table at which I sat, I used to grind my teeth at them, and felt intense enjoyment when I succeeded in making anybody unhappy. I almost did succeed. For the most part they were all timid people—of course, they were petitioners. But of the uppish ones there was one officer in particular I could not endure. He simply would not be humble, and clanked his sword in a disgusting way. I carried on a feud with him for eighteen months over that sword. At last I got the better of him. He left off clanking it. That happened in my youth, though.

But do you know, gentlemen, what was the chief point about my spite? Why, the whole point, the real sting of it lay in the fact that continually, even in the moment of the acutest spleen, I was inwardly conscious with shame that I was not only not a spiteful but not even an embittered man, that I was simply scaring sparrows at random and amusing myself by it. I might foam at the mouth, but bring me a doll to play with, give me a cup of tea with sugar in it, and maybe I should be appeased. I might even be genuinely touched, though probably I should grind my teeth at myself afterwards and lie awake at night with shame for months after. That was my way.

Get the Standard Ebooks Garnett translation of Notes from the Underground

44,336 words (2 hours 42 minutes). This is an improved version of Project Gutenberg 600.

Available as an ebook.

Get the Garnett translation of Notes from the Underground

Contains: “White Nights”, “Notes from Underground”, “A Faint Heart”, “A Christmas Tree and a Wedding”, “Polzunkov”, “A Little Hero”, and “Mr. Prohartchin”

Available as an ebook.

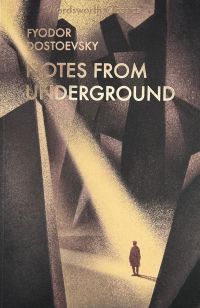

Get the Wordsworth Classics Garnett translation of Notes from the Underground

Introduction and Notes by David Rampton, Department of English, University of Ottowa. Also includes: A Christmas Tree and a Wedding, Bobok, and A Gentle Spirit.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9781840225778, 720 pages).

Get the Dover Thrift Editions Garnett translation of Notes from the Underground

Reprinted from White Nights and Other Stories, The Macmillan Company, New York, 1918. Ebook version also available.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780486270531, 96 pages).

Get the AmazonClassics Garnett translation of Notes from the Underground

Includes editorial revisions. Paperback also available.

Available as an ebook (ISBN 9781542099585).

Get the Hackett Classics Garnett translation of Notes from the Underground

Includes an introduction by Kevin Aho and Charles Guignon and a selected bibliography. According to "Notes from Underground In English by Ira Nadel": “[T]he text is a light revision of the Garnett translation replacing archaic terms or British idioms with contemporary American English.”

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780872209053, 144 pages).

Get the Hackett Classics Garnett translation of Notes from the Underground

Includes an introduction by Kevin Aho and Charles Guignon and a selected bibliography. According to "Notes from Underground In English by Ira Nadel": “[T]he text is a light revision of the Garnett translation replacing archaic terms or British idioms with contemporary American English.”

Available as an ebook (ISBN 9781603842525).

Who was David Magarshack?

David Magarshack was a British fiction writer and who translated works by Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Goncharov, Gogol, and Chekhov and wrote biographies of several Russian authors, including Dostoyevsky. He was born in Riga, Russia (a city in present-day Latvia), and moved to England in his 20s, eventually becoming a naturalized citizen.

In addition to Notes from Underground, Magarshack translated Crime and Punishment, The Devils (Demons), The Idiot, The Brothers Karamazov and a volume entitled “Dostoevsky’s Occasional Writings”.

“Notes from Underground In English by Ira Nadel”

“[E]arly twentieth century translators… tended to be émigrés, such as David Magarshack who arrived in England from Riga in 1920 and, after an unsuccessful attempt at journalism and then crime writing, turned to translations. For the Penguin Russian Classics series, he produced a number of Russian translations, notably Crime and Punishment and Notes from Underground. Magarshack’s translations were expressed in relaxed language but responsive to the textual complexities of Dostoevsky, matters of repetition, the intonation of obsession and what Nabokov called Dostoevsky’s “vulgar soapbox eloquence” [Nabokov 1981: 118]. One important aspect of Magarshack’s work is that it was for him a way of earning a living: for his first translation, he received an advance of £200 plus royalties of seven and a half percent.”

About the Magarshack translation of Notes from Underground

Title of book: The Best Short Stories of Fyodor Dostoevsky

Contains: “White Nights”, “The Honest Thief”, “The Christmas Tree and a Wedding”, “The Peasant Marey”, “Notes from the Underground”, “A Gentle Creature”, and “The Dream of a Ridiculous Man”

Also includes: A biographical note, an introduction, commentary, and a reading group guide.

This translation uses British spelling.

Previously printed in collections titled Great Short Works of Fyodor Dostoevsky and Best Stories of Fyodor Dostoevsky.

Extract from the Magarshack translation of Notes from Underground

First ~500 words of Chapter 1 (from photos on Reddit):

I am a sick man . . . . I am a spiteful man. No, I am not a pleasant man at all. I believe there is something wrong with my liver. however, I don’t know a damn thing about my liver; neither do I know whether there is anything really wrong with me. I am not under medical treatment, and never have been, though I do respect medicine and doctors. In addition, I am extremely superstitious, at least sufficiently so to respect medicine. (I am well educated enough not to be superstitious, but I am superstitious for all that.) The truth is, I refuse medical treatment out of spite. I don’t suppose you will understand that. Well, I do. I don’t expect I shall be able to explain to you who it is I am actually trying to annoy in this case by my spite; I realize full well that I can’t “hurt” the doctors by refusing to be treated by them; I realise better than any one that by all this I am only hurting myself and no one else. Still, the fact remains that if I refuse to be medically treated, it is only out of spite. My liver hurts me—well, let it damn well hurt—the more it hurts the better.

I have been living like this a long time—about twenty years, I should think. I am forty now. I used t be in the Civil Service, but I am no longer there now. I was a spiteful civil servant. I was rude and took pleasure in being rude. Mind you, I never accepted any bribes, so that I had at least to find something to compensate myself for that. (A silly joke, but I shan’t cross it out. I wrote it thinking it would sound very witty, but now that I have seen myself that I merely wanted to indulge in a bit of contemptible bragging, I shall let it stand on purpose!)

Whenever people used to come to my office on some business, I snarled at them and felt as pleased as Punch when I succeeded in making one of them really unhappy. I nearly always did succeed. They were mostly a timid lot: what else can you expect people who come to a government office to be? But among the fine gentlemen who used to come to me to make inquiries there was one officer in particular whom I could not bear. He would not submit with a good grace and he had a disgusting habit of rattling his sword. For sixteen months I waged a regular war with him over that sword. In the end, I got the better of him. He stopped rattling. However, all this happened a long time ago when I was still a young man.

Get the Modern Library Magarshack translation of Notes from the Underground

The Best Short Stories of Fyodor Dostoevsky. Contains: White Nights, The Honest Thief, The Christmas Tree and a Wedding, The Peasant Marey, Notes from the Underground, A Gentle Creature, and the Dream of a Ridiculous Man. Includes a biographical note, introduction by David Magarshack, commentary by Stefan Zweig and Andre Gide, and reading group guide.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780375756887, 320 pages).

Get the Modern Library Magarshack translation of Notes from the Underground

The Best Short Stories of Fyodor Dostoevsky. Contains: White Nights, The Honest Thief, The Christmas Tree and a Wedding, The Peasant Marey, Notes from the Underground, A Gentle Creature, and the Dream of a Ridiculous Man. Includes a biographical note, introduction by David Magarshack, commentary by Stefan Zweig and Andre Gide, and reading group guide.

Available as an ebook (ISBN 9780307824080).

Get the The Folio Society Magarshack translation of Notes from the Underground

Illustrated by Harry Brockway. Introduced By Joyce Carol Oates.

Available as a slipcased hardcover.

Who were Constance Garnett and Ralph E. Matlaw?

See above for information on Constance Garnett.

Ralph E. Matlaw was a professor at Harvard, Princeton, and the University of Chicago and the editor or translator of multiple works in Russian.

» New York Times: Obituary of Ralph Matlaw

About the Garnett and Matlaw translation of Notes from Underground

Title of book: Notes from Underground, the Grand Inquisitor

Contains: “Notes from Underground” and “The Grand Inquisitor”

Also includes: an introduction and 4 appendixes (Chernyshevsky: Excerpts from What Is to Be Done?, Dostoevsky: Excerpts from Winter Notes on Summer Impressions and Excerpts from Dostoevsky’s Letters, Shchedrin: The Swallows, and Dostoevsky: Mr. Shchedrin, or, Schism among the Nihilists)

From the Translator’s Note by Ralph E. Matlaw:

“The Constance Garnett versions of Notes from Underground and “The Grand Inquisitor” have been thoroughly revised. Some changes were made for accuracy and consistency; others so that the text might approximate Dostoevsky’s idiosyncratic style.”

Extract from the Garnett and Matlaw translation of Notes from Underground

First ~500 words of Chapter 1 (from photos on Reddit):

I am a sick man . . . I am a spiteful man. I am an unpleasant man. I think my liver is diseased. However, I don’t know beans about my disease, and I am not sure what is bothering me. I don’t treat it and never have, though I respect medicine and doctors. Besides, I am extremely superstitious, let’s say sufficiently so to respect medicine. (I am educated enough not to be superstitious, but I am.) No, I refuse to treat it out of spite. You probably will not understand that. Well, but I understand it. Of course, I can’t explain to you just whom I am annoying in this case by my spite. I am perfectly well aware that I cannot “get even” with the doctors by not consulting them. I know better than anyone that I thereby injure only myself and no one else. But still, if I don’t treat it, it is out of spite. My liver is bad, well then—let it get even worse!

I have been living like that for a long time now—twenty years. I am forty now. I used to be in the civil service, but no longer am. I was a spiteful official. I was rude and took pleasure in being so. After all, I did not accept bribes, so I was bound to find a compensation in that, at least. (A bad joke but I will not cross it out. I wrote it thinking it would sound very witty; but now that I see myself that I only wanted to show off in a despicable way, I will purposely not cross it out!) When petitioners would come to my desk for information I would gnash my teeth at them, and feel intense enjoyment when I succeeded in distressing some one. I was almost always successful. For the most part they were all timid people—of course, they were petitioners. but among the fops there was one officer in particular I could not endure. He simply would not be humble, and clanked his sword in a disgusting way. I carried on a war with him for eighteen months over that sword. At last I got the better of him. He left off clanking it. However, that happened when I was still young. But do you know, gentlemen, what the real point of my spite was? Why, the whole trick, the real vileness of it lay in the fact that continually, even in moments of the worst spleen, I was inwardly conscious with shame that I was not only spiteful but not even an embittered man, that I was simply frightening sparrows at random and amusing myself by it. I might foam at the mouth, but bring me some kind of toy, give me a cup of tea with sugar, and I would be appeased. My heart might even be touched, though probably I would gnash my teeth at myself afterward and lie awake at night with shame for months after. That is the way I am.

Get the Plume Matlaw translation of Notes from Underground

Notes from Underground, the Grand Inquisitor. Introduction by Ralph E. Matlaw. Includes "relevant works by Chernyshevsky, Shchedrin and Dostoevsky".

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780452285583, 272 pages).

Get the Plume Matlaw translation of Notes from Underground

Notes from Underground, the Grand Inquisitor. Introduction by Ralph E. Matlaw.

Available as an ebook (ISBN 9781101666234).

Who was Andrew R. MacAndrew?

Andrew R. MacAndrew was a professor at the University of Virginia and translator of plays and novels in Russian, including The Brothers Karamazov and The Devils (Demons).

About the MacAndrew translation of Notes from Underground

Title of book: Notes from Underground

Contains: “Notes from Underground”, “White Nights”, “The Dream of a Ridiculous Man” and selections from “The House of the Dead”. (Selections from “The House of the Dead”: Baklushkin’s Story, Akulka’s Husband, In the Hospital.)

Also includes: an afterword by Andrew R. MacAndrew, an introduction by Ben Marcus, and a selected bibliography.

This translation uses American spelling.

“Notes from Underground In English by Ira Nadel”

“Among all the introductions or afterwords in these English translations, only MacAndrew engages with the Soviet response to Dostoevsky’s writing.”

Extract from the MacAndrew translation of Notes from Underground

First ~500 words of Chapter 1:

I’m a sick man . . . a mean man. There’s nothing attractive about me. I think there’s something wrong with my liver. But, actually, I don’t understand a damn thing about my sickness; I’m not even too sure what it is that’s ailing me. I’m not under treatment and never have been, although I have great respect for medicine and doctors. moreover, I’m morbidly superstitious—enough, at least, to respect medicine. with my education I shouldn’t be superstitious, but I am just the same. No, I’d say I refuse medical help simply out of contrariness. I don’t expect you to understand that, but it’s so. Of course, I can’t explain whom I’m trying to fool this way. I’m fully aware that I can’t spite the doctors by refusing their help. I know very well that I’m harming myself and no one else. But still, it’s out of spite that I refuse to ask for the doctors’ help. So my liver hurts? Good, let it hurt even more!

I’ve been living like this for a long time, twenty years or so. I’m forty now. I used to be in government service, but I’m not any more. I was a nasty official. I was rude and enjoyed being rude. Why, since I took no bribes, I had to make up for it somehow. (That’s a poor attempt at wit, but I won’t delete it now. I wrote it thinking it’d sound very sharp. But now I realize that it’s nothing but vulgar showing off, so I’ll let it stand if only for that reason.)

When petitioners came up to my desk for information, I snarled at them and felt indescribably happy whenever I managed to make one of them feel miserable. Being petitioners, they were a meek lot. One, however, wasn’t. He was an officer, and I had a special loathing for him. He just wouldn’t be subdued. He had a special way of letting his saber rattle. Disgusting. For eighteen months I waged war with him about that saber. I won out in the end, and he stopped the thing from rattling. All this, however, happened when I was still young. But shall I tell you what it was really all about? Well, the real snag, the most repulsive aspect of my nastiness, was that, even when I was at my liverish worst, I was constantly aware that I was not really wicked nor even embittered, that I was simply chasing pigeons, you might say, and thus passing the time. And so I might be frothing at the mouth, but if you had brought me a doll to play with or had offered me a nice cup of tea with sugar, chances are I would have calmed down. I’d even have been deeply touched, although, angry at myself, I would be certain to gnash my teeth later and be unable to sleep for several months. But that’s the way it was.

Get the Signet Classics MacAndrew translation of Notes from Underground

Includes White Nights, The Dream of a Ridiculous Man and slelections from The House of the Dead. Afterword by Andrew R. MacAndrew. Introduction by Ben Marcus.

Available as a mass-market paperback (ISBN 9780451529558, 256 pages).

Who was/is Serge Shishkoff?

As far as I can tell, Serge Shishkoff was a Russian language lecturer at the University of Michigan.

About the Shishkoff translation of Notes from Underground

Title of book: Notes from Underground

Contains: Notes from Underground and related materials (no other stories)

Contains an introduction by editor Robert G. Durgy, Pennsylvania State University, a translator’s note by Serge Shishkoff, 6 essays of criticism and commentary, and a bibliography.

Essays: Notes from Underground by Konstantin Mochulsky; Nihilism and Notes from Underground by Joseph Frank; Structure and Integration in Notes from Underground by Ralph E. Matlaw; Monologue Speech of the Hero, and Narrative discourse in the Stories of Dostoevsky—Notes from Underground by M.M. Bakhtin; Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground by Isadore Traschen; and Dostoevsky’s Metaphor of the “Underground” by Monroe C. Beardsley.

This translation uses American spelling.

From the Introduction by Robert G. Durgy:

“The critical articles on Notes from Underground collected in this edition, though they represent various areas of twentieth-century Dostoevsky scholarship and criticism, largely follow a consistent point of view. That is, I have attempted to present here not only that type of Dostoevsky criticism which is concerned with the peculiar ideological meaning of the work and its relationship to the author’s ideological development, but which also responds to two popular misconceptions that have long preoccupied Dostoevsky’s critics: the first, that Dostoevsky’s characters are ‘merely’ mouthpieces for his own, personal ideas; the second—an outgrowth of the first—that Dostoevsky was a ‘careless’ writer, pouring forth his ideas with a ‘shocking’ lack of artistic form.”

From the Translator’s note by Serge Shishkoff:

“The chief problem of any literary translation lies not in transposing the meaning of what is said from one language to another, but in duplicating the style in which it is said…. The narrator of Notes is supposed to be an educated man who is speaking, or rather writing, informally. For this reason Dostoevsky endowed him with very colorful speech that contains, along with the sophisticated vocabulary needed to convey the complex ideas found in Notes, a great number of colloquial expressions, and even some slang. Furthermore, the narrator’s speech changes as his mood changes…. In attempting to make my translation as accurate as possible, I have avoided omitting, changing, or adding anything at all. I have even tried to duplicate the few grammatical and syntactical errors that Dostoevsky made his narrator commit…. Dostoevsky’s paragraphing appears capricious, and some translators have felt compelled to alter it. The basic principle of breaking a text into paragraphs, however, is the same in Russian and in English, and Dostoevsky’s ‘capriciousness’ in paragraphing is intentional—he uses it as a device to achieve certain effects in the same way as he uses the division into chapters. I have, therefore, kept Dostoevsky’s paragraphing throughout.”

“Notes from Underground In English by Ira Nadel”

“This substantial edition offers an extensive introduction, a useful note by the translator and six important essays…. The ‘Translator’s Note’ is the clearest presentation among English translators of the challenges and pitfalls of translating Dostoevsky and Notes from Underground.”

Get the Shishkoff translation of Notes from Underground

Originally published in 1969 in New York by Thomas Y. Crowell Company as part of The Crowell Critical Library series. ISBN: 0690588216, 262 pages.

This edition is out of print. You may be able to find a second-hand copy.

Reissued in 1982 by University Press of America. ISBN 081912415X, 262 pages.

This edition is out of print. You may be able to find a second-hand copy.

Extract from the Shishkoff translation of Notes from Underground

First ~500 words of Chapter 1:

I am a sick man . . . I am a nasty man. A truly unattractive man. I think there’s something wrong with my liver. But then again, I don’t understand a damn thing about my sickness, and I don’t know for sure what’s wrong with me. I’m not seeing a doctor about it and never have, even though I do have respect for medicine and doctors. What’s more, I am superstitious to the extreme; well, at least to the extent of respecting medicine. (I am sufficiently educated not to be superstitious, but I am.) No sir, it’s out of nastiness that I don’t want to see a doctor. you, my dear sir, probably don’t understand that. Well, I do. Of course, I can’t explain exactly who’ll be put in a pickle in this case by my nastiness; I know full well that I can in no way “foul up” even the doctors by not going to them for treatment; I know better than anyone that all this will harm just me alone and no one else. But, nonetheless, if I don’t get treatment, it’s from nastiness. My liver hurts, all right then—let it hurt even worse!

I have been living this way for a long time—twenty years or so. I’m forty now. I used to have a post in the civil service, but I don’t any more. I was a nasty official. I was rude and took pleasure in it. After all, I never took a bribe, so that was the least I could do to compensate myself for it. (A poor joke, but I am not going to cross it out. I wrote it thinking that it would be very clever, but now that I myself see that I only wanted to show off abominably, I purposely won’t cross it out!) When petitioners looking for information happened to come to the desk where I sat, I gnashed my teeth at them, and I felt an insatiable delight when I succeeded in upsetting someone. I almost always succeeded. For the most part they were timid people—you know, petitioners. But of the swaggerers I particularly despised a certain officer. He just wouldn’t submit and clanged his saber in an obnoxious way. For a year and a half I carried on a war with him over that saber. In the end I prevailed. He stopped clanging. But then, that was back in my youth. But do you know, gentlemen, what the main point of my nastiness was? Well, what the whole thing consisted of, what made it such a vile mess, was that every moment, even at the moment of greatest rancor, I shamefully recognized inwardly that I was not only not a nasty man but not even a disgruntled one, that I was only needlessly frightening sparrows and satisfying my whims that way. I might be frothing at the mouth, but bring me some little trinket, give me a bit of tea with sugar, and I’d probably calm right down. I might even be touched to the heart, even though afterwards I’d surely gnash my teeth at myself, and suffer from insomnia, out of shame, for several months. That’s the way I am.

Who was Jessie Coulson?

Jessie Coulson was a British lexicographer who worked on the Oxford English Dictionary and complied a Russian-English dictionary and a translator of Russian works by Dostoevsky, Turgenev, Gorky, and Chekhov.

About the Coulson translation of Notes from Underground

Title of book: Notes from Underground and The Double

Contains: “Notes from Underground” and “The Double”

Depending on the edition, this translation may also contain a brief biography of Dostoevsky, an introduction by Jessie Coulson, and a chronology by David McDuff (added in 2003).

This translation uses British spelling.

Extract from the Coulson translation of Notes from Underground

First ~500 words of Chapter 1 (from Amazon):

I am a sick man…. I am an angry man. I am an unattractive man. I think there is something wrong with my liver. But I don’t understand the least thing about my illness, and I don’t know for certain what part of me is affected. I am not having any treatment for it, and never have had, although I have a great respect for medicine and for doctors. I am besides extremely superstitious, if only in having such respect for medicine. (I am well educated enough not to be superstitious, but superstitious I am.) No, I refuse treatment out of spite. That is something you will probably not understand. Well, I understand it. I can’t of course explain who my spite is directed against in this matter; I know perfectly well that I can’t ‘score off’ the doctors in any way by not consulting them; I know better than anybody that I am harming nobody but myself. All the same, if I don’t have treatment, it is out of spite. Is my liver out of order? — let it get worse!

I have been living like this for a long time now—about twenty years. I am forty. I once used to work in the government service but I don’t now. I was a bad civil servant. I was rude, and I enjoyed being rude. After all, I didn’t take bribes, so I had to have some compensation. (A poor witticism; but I won’t cross it out. When I wrote it down, I thought it would seem very pointed: now, when I see that I was simply trying to be clever and cynical, I shall leave it in on purpose.) When people used to come to the desk where I sat, asking for information, I snarled at them, and was hugely delighted when I succeeded in hurting somebody’s feelings. I almost always did succeed. They were mostly timid people—you know what people looking for favours are like. But among the swaggerers there was one officer I simply couldn’t stand. He absolutely refused to be intimidated, and he made a disgusting clatter with his sword. I carried on a campaign against him for eighteen months over that sword. I won in the end. He stopped making a clatter with it. This, however, was when I was still young. But do you know what was the real point of my bad temper? The main point, and the supreme nastiness, lay in the fact that even at my moments of greatest spleen, I was constantly and shamefully aware that not only was I not seething with fury, I was not even angry; I was simply scaring sparrows for my own amusement. I might be foaming at the mouth, but bring me some sort of toy to play with, or a nice sweet cup of tea, and I would calm down and even be stirred to the depths, although I would probably turn on myself afterwards, and suffer from insomnia for months. That was always my way.

Get the Penguin Classics Coulson translation of Notes from Underground

Notes from Underground and the Double. Introduction by Jessie Coulson. 1972.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780140442526, 288 pages).

Get the Penguin Classics Coulson translation of Notes from Underground

Notes from Underground and the Double. Introduction by Jessie Coulson. 1972.

Available as an ebook.

Who was Mirra Ginsburg?

Mirra Ginsburg was a Russian-American writer and translator. Among her translations are Bulgakov’s Fatal Eggs, Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We, and Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita.

» Mirra Ginsburg (Jewish Women’s Archive)

» Mirra Ginsburg (Encyclopedia of Science Fiction)

The Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Columbia University in the City of New York has a collection of Mirra Ginsburg’s papers.

About the Ginsburg translation of Notes from Underground

Title of book: Notes from Underground

Contains: Notes from Underground

Also includes an introduction by Donald Fanger, a note on the translation, and a total of 23 endnotes.

The decorative subtitle on an early printing says, “The Impassioned Confessions of a Solitary Man”.

This translation uses American spelling.

From the Translator’s note by Mirra Ginsburg:

“In style, Notes from Underground, despite its title, is a spoken, not a written book. The breath is therefore all the more important. I broke up the extremely long paragraphs, which often obscure the complexity of meanings, into shorter ones wherever I felt that clarity demanded it, wherever I felt the speaker would have to pause.”

“Notes from Underground In English” by Ira Nadel

“Fanger’s introduction is one of the most critically insightful among the current set of English translations.”

Extract from the Ginsburg translation of Notes from Underground

First ~500 words of Chapter 1 (from Penguin Random House):

I am a sick man. . . . I am a spiteful man. An unattractive man. I think that my liver hurts. But actually, I don’t know a damn thing about my illness. I am not even sure what it is that hurts. I am not in treatment and never have been, although I respect both medicine and doctors. Besides, I am superstitious in the extreme; well, at least to the extent of respecting medicine. (I am sufficiently educated not to be superstitious, but I am.) No, sir, I refuse to see a doctor simply out of spite. Now, that is something that you probably will fail to understand. Well, I understand it. Naturally, I will not be able to explain to you precisely whom I will injure in this instance by my spite. I know perfectly well that I am certainly not giving the doctors a “dirty deal” by not seeking treatment. I know better than anyone that I will only harm myself by this, and no one else. And yet, if I don’t seek a cure, it is out of spite. My liver hurts? Good, let it hurt still more!

I have been living like this for a long time-about twenty years. Now I am forty. I used to be in the civil service; today I am not. I was a mean official. I was rude, and found pleasure in it. After all, I took no bribes, and so I had to recompense myself at least by this. (A poor joke, but I will not cross it out. I wrote it, thinking it would be extremely witty; but now I see that it was only a vile little attempt at showing off, and just for that I’ll let it stand!)

When petitioners came to my desk seeking information, I gnashed my teeth at them, and gloated insatiably whenever I succeeded in distressing them. I almost always succeeded. Most of them were timid folk: naturally-petitioners. But there were also some fops, and among these I particularly detested a certain officer. He absolutely refused to submit and clattered revoltingly with his sword. I battled him over that sword for a year and a half. And finally I got the best of him. He stopped clattering. This, however, happened long ago, when I was still a young man. But do you know, gentlemen, what was the main thing about my spite? Why, the whole point, the vilest part of it, was that I was constantly and shamefully aware, even at moments of the most violent spleen, that I was not at all a spiteful, no, not even an embittered, man. That I was merely frightening sparrows to no purpose, diverting myself. I might be foaming at the mouth, but bring me a doll, give me some tea, with a bit of sugar, and I’d most likely calm down. Indeed, I would be deeply touched, my very heart would melt, though later I’d surely gnash my teeth at myself and suffer from insomnia for months. That’s how it is with me.

Get the Bantam Classics Ginsburg translation of Notes from Underground

Introduction by Donald Fanger.

Available as a mass-market paperback (ISBN 9780553211443, 176 pages).

Who is Michael R. Katz?

Michael Katz is an Emeritus Professor of Russian and East European Studies and the translator of over a dozen Russian novels, including Crime and Punishment, The Brothers Karamazov, and Devils (Demons).

About the Katz translation of Notes from Underground

Title of book: Notes from Underground

Contains: Notes from Underground

Norton has published a version (in The Norton Library series) with just the novella, and another version (in the Norton Critical Editions series) with critical essays. The first Norton Critical Edition was published in 1989, and the second Norton Critical Edition was published in 2000.

From “A Note on the Translation” by Michael R. Katz in the Norton Library edition:

“Notes from Underground… remains one of the most challenging texts to translate in all of Russian literature, beginning with the first three lines of the work. I have previously translated these lines as: ‘I am a sick man…. I am a spiteful man. I am an unattractive man.’ A former student at Middlebury College [(Jesse Bennett)], after hearing my lament about the complexity of that opening, suggested the following smart, succinct alternative: ‘I’m a sick man. A spiteful man. Repulsive.’ I have adopted his version for this Norton Library edition.”

Dostoevsky Studies, New Series: “A Brief Note on the Translation of the Opening Lines of Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground” by Michael R. Katz

“His elegant solution abandoned the repetition of pronoun and noun, and instead aimed to replicate the foregrounding of the adjective in English. He also chose a stronger synonym for the third epithet. His version is as follows: I’m a sick man. A spiteful man. Repulsive. His name is Jesse Bennett; he hails from Kailua Kona, Hawaii and he graduated from Middlebury College in 2011. This experience demonstrates, yet again, the collaborative nature of translation.”

This translation uses American spelling.

Extract from the Katz translation of Notes from Underground

First ~500 words of Chapter 1 (from first Norton Critical Edition edition):

I am a sick man. . . . I am a spiteful man. I am a most unpleasant man. I think my liver is diseased. Then again, I don’t know a thing about my illness; I’m not even sure what hurts. I’m not being treated and never have been, though I respect both medicine and doctors. Besides, I’m extremely superstitious—well at least enough to respect medicine. (I’m sufficiently educated not to be superstitious; but I am, anyway.) No, gentlemen, it’s out of spite that I don’t wish to be treated. Now then, that’s something you probably won’t understand. Well, I do. Of course, I won’t really be able to explain to you precisely who will be hurt by my spite in this case; I know perfectly well that I can’t possibly “get even” with doctors by refusing their treatment; I know better than anyone that all this is going to hurt me alone, and no one else. Even so, if I refuse to be treated, it’s out of spite. My liver hurts? Good, let it hurt even more!

I’ve been living this way for some time—about twenty years. I’m forty now. I used to be in the civil service. But no more. I was a nasty official. I was rude and took pleasure in it. After all, since I didn’t accept bribes, at least I had to reward myself in some way. (That’s a poor joke, but I won’t cross it out. I wrote it thinking that it would be very witty; but now, having realized that I merely wanted to show off disgracefully, I’ll make a point of not crossing it out!) When petitioners used to approach my desk for information, I’d gnash my teeth and feel unending pleasure if I succeeded in causing someone distress. I almost always succeeded. For the most pert they were all timid people: naturally since they were petitioners. But among the dandies there was a certain officer whom I particularly couldn’t bear. He simply refused to be humble, and he clanged his saber in a loathsome manner. I waged war with him over that saber for about a year and a half. At last I prevailed. He stopped clanging. All this, however, happened a long time ago, during my youth. But do you know, gentlemen, what the main component of my spite really was? Why, the whole point, the most disgusting thing, was the fact that I was shamefully aware at every moment, even at the moment of my greatest bitterness, that not only was I not a spiteful man, I was not even an embittered one, and that I was merely scaring sparrows to no effect and consoling myself by doing so. I was foaming at the mouth—but just bring me some trinket to play with, just serve me a nice cup of tea with sugar, and I’d probably have calmed down. My heart might even have been touched, although I’d probably have gnashed my teeth out of shame and then suffered from insomnia for several months afterward. That’s just my usual way.

Get the Norton Critical Editions Katz translation of Notes from Underground

2nd Edition. Includes the novella, 6 backgrounds and sources, 8 responses, 11 critical essays, a chronology, and selected bibliography.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780393976120, 272 pages).

Get the The Norton Library Katz translation of Notes from Underground

Includes an introduction, note on the translation, chronology.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780393870862, 176 pages).

Get the The Norton Library Katz translation of Notes from Underground

Includes an introduction, note on the translation, chronology.

Available as an ebook (ISBN 9780393870664).

Who is Jane Kentish?

Oxford University Press says: “Jane Kentish works as a lecturer in Byzantine art and as a translator. She has translated Netochka Nezvanova by Dostoevsky and Tolstoy’s A Confession and Other Religious Writings.” She has also lectured in early Russian history and art at the University of Sussex.

About the Kentish translation of Notes from Underground

Title of book: Notes from the Underground and The Gambler

Contains: “Notes from the Underground” and “The Gambler”

Also includes a brief bio of Dostoevsky, an introduction by Malcolm Jones, a (one-sentence) note on the translation, a select bibliography, a chronology, and explanatory endnotes by Malcolm Jones.

This translation uses British spelling.

Extract from the Kentish translation of Notes from Underground

First ~500 words of Chapter 1 (from Amazon):

I am a sick man … I’m a spiteful man. I’m an unattractive man. I think there is something wrong with my liver. But I cannot make head or tail of my illness and I’m not absolutely certain which part of me is sick. I’m not receiving any treatment, nor have I ever done, although I do respect medicine and doctors. Besides, I’m still extremely superstitious, if only in that I respect medicine. (I’m sufficiently well educated not to be superstitious, but I am.) No, it’s out of spite that I don’t want to be cured. You’ll probably not see fit to understand this. But I do understand it. Of course, I won’t be able to explain to you precisely whom I will harm in this instance by my spite; I know perfectly well that I cannot in any way ‘sully’ the doctors by not consulting them. I know better than anyone that in doing this I shall harm no one but myself. Anyway, if I’m not receiving medical treatment it’s out of spite. If my liver is hurting, then let it hurt all the more!

I’ve been living like this for a long time—for about twenty years. I’m now forty. I used to work for the government but I no longer work. I was a spiteful civil servant. I was rude and I enjoyed being rude. you see, I didn’t accept bribes so I had to reward myself in this way. (That’s a lousy joke, but I won’t delete it. I wrote it thinking that it would come across very wittily; but now that I can see that I only wanted to show off in a vulgar way, I’m deliberately not going to cross it out.) When people used to come with their enquiries to the desk where I sat I would bare my teeth at them and I used to feel an overwhelming sense of pleasure whenever I succeeded in upsetting someone. It nearly always worked. The majority of them were timid folk—we all know what petitioners are like. But amidst the fops there was one particular officer whom I couldn’t stand. He simply would not give in and used to rattle his sword loathsomely. He and I waged war over this sword for a year and a half. Finally I won. He stopped the rattling. This, however, took place in my youth. Gentlemen, do you know what lay at the heart of my malice? The main point, and indeed the most sordid thing about it, was that, even during moments of extreme biliousness, I was constantly and shamefully aware that not only was I not spiteful, I was not even embittered. I was simply comforting myself by scaring sparrows in vain. I might be foaming at the mouth, but bring me some kind of toy, give me a cup of sugary tea, and it’s more than likely I’d calm down. I might even be spiritually moved, but I’d be certain to snarl at myself afterwards and suffer insomnia for several months out of shame. I’ve always been like this.

Get the Oxford Kentish translation of Notes from the Underground

Notes from the Underground, and The Gambler. Introduction by Malcolm Jones.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780199536382, 320 pages).

Get the Oxford Kentish translation of Notes from the Underground

Notes from the Underground, and The Gambler. Introduction by Malcolm Jones.

Available as an ebook (ISBN 9780191505805).

Who are Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky?

Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky are the American/Russian husband-and-wife team who have produced bestselling but divisive translations of many Russian classics, including Crime and Punishment, The Brothers Karamazov, The Idiot, Demons, The Master and Margarita, Anna Karenina, and War and Peace. Separately, Pevear has also translated works in French, Italian, Spanish, and Greek, including The Three Musketeers.

About the Pevear and Volokhonsky translation of Notes from Underground

Title of book: Notes from Underground

Contains: Notes from Underground

Also includes an introduction by Richard Pevear, a select bibliography, a chronology, and endnotes.

This translation uses American spelling.

From the Introduction by Richard Pevear:

“There is… one tradition of mistranslation attached to Notes from Underground that rasises something more than a question of ‘mere tone.’ The second sentence of the book, Ya zloy chelovek, has most often been rendered as ‘I am a spiteful man.’ Zloy is indeed at the root of the Russian word for ‘spiteful’ (zlobynyi), but it is a much broader and deeper word, meaning ‘wicked,’ ‘bad,’ ‘evil.’ The wicked witch in Russian folktales is zlaya ved’ma (zlaya being the faminine of zloy). The opposite of zloy is dobryi, ‘good,’ as in ‘good fairy’ (dobraya feya). This opposition is of great importance for Notes from Underground; indeed it frames the book, from ‘I am a wicked man’ at the start to the outburst close to the end: ‘The won’t let me… I can’t be … good!” We can talk forever about the inevitable loss of nuances in translating from Russian into English (or from any language into any other), but the translation of zloy as ‘spiteful’ instead of ‘wicked’ is not inevitable, nor is it a matter of nuance.”

“Notes from Underground In English” by Ira Nadel

“With its introduction, ‘Chronology,’ and notes, this useful translation by two distinguished translators, who also did The Brothers Karamazov, Crime and Punishment, Demons, and The Idiot, remains a valuable version, although it is almost thirty years old…. A three-page section ends the introduction focusing on the style,

language and natural challenges of translating Notes. The editors examine in detail Dostoevsky’s reliance on blunt and even crude terms, maintained in the translation by Pevear and Volokhonsky to sustain the tone of the original.”

Extract from the Pevear and Volokhonsky translation of Notes from Underground

First ~500 words of Chapter 1 (from Amazon):

I am a sick man . . . I am a wicked man. An unattractive man. I think my liver hurts. However, I don’t know a fig about my sickness, and am not sure what it is that hurts me. I am not being treated and never have been, though I respect medicine and doctors. What’s more, I am also superstitious I the extreme; well, at least enough to respect medicine. (I’m sufficiently educated not to be superstitious, but I am.) No, sir, I refuse to be treated out of wickedness. Now, you will certainly not be so good as to understand this. Well, sir, but I understand it. I will not, of course, be able to explain to you precisely who is going to suffer in this case from my wickedness; I know perfectly well that I will in no way “muck things up” for the doctors by not taking their treatment; I know better than anyone that by all this I am harming only myself and no one else. But still, if I don’t get treated, it is out of wickedness. My liver hurts; well, then let it hurt even worse!

I’ve been living like this for a long time — about twenty years. I’m forty now. I used to be in the civil service; I no longer am. I was a wicked official. I was rude, and took pleasure in it. After all, I didn’t accept bribes, so I had to reward myself at least with that. (A bad witticism, but I won’t cross it out. I wrote it thinking it would come out very witty; but now, seeing for myself that I simply had a vile wish to swagger — I purposely won’t cross it out!) When petitioners would come for information to the desk where I sat — I’d gnash my teeth at them, and felt an inexhaustible delight when I managed to upset someone. I almost always managed. They were timid people for the most part: petitioners, you know. But among the fops there was one officer I especially could not stand. He simply refused to submit and kept rattling his sabre disgustingly. I was at war with him over that sabre for a year and a half. In the end, I prevailed. He stopped rattling. However, that was still in my youth. But do you know, gentlemen, what was the main point about my wickedness? The whole thing precisely was, the greatest nastiness precisely lay in my being shamefully conscious every moment, even in moments of the greatest bile, that I was not only a wicked but was not even an embittered man, that I was simply frightening sparrows in vain, and pleasing myself with it. I’m foaming at the mouth, but bring me some little doll, give me some tea with a bit of sugar, and maybe I’ll calm down. I’ll even wax tenderhearted, though afterwards I’ll certainly gnash my teeth at myself and suffer from insomnia for a few months out of shame. Such is my custom.

Get the Everyman's Library Pevear and Volokhonsky translation of Notes from Underground

Introduction by Richard Pevear.

Available as a hardcover (ISBN 9781400041916, 160 pages).

Get the Vintage Classics Pevear and Volokhonsky translation of Notes from Underground

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780679734529, 176 pages).

Get the Vintage Classics Pevear and Volokhonsky translation of Notes from Underground

Available as an ebook (ISBN 9780307784643).

Who is Hugh Aplin?

Alma Books says: “Hugh Aplin worked at the Universities of Leeds and St Andrews before taking up his current post as Head of Russian at Westminster School, London. His previous translations are too many to mention, but include books by Chekhov, Gogol, Dostoevsky, Turgenev, Zamyatin, Bulgakov, Tolstoy, Bunin and, more recently, Gorky.”

About the Aplin translation of Notes from Underground

Title: Notes from the Underground.

Contains: Notes from the Underground.

Includes a foreword by Will Self.

This translation presumably uses British spelling.

Get the Aplin translation of Notes from Underground

Published by UK publisher Hesperus Press. ISBN 9781843911265, 150 pages.

This edition is out of print. You may be able to find a second-hand copy.

Extract from the Aplin translation of Notes from Underground

First ~200 words of Chapter 1 (from Reddit):

I’m a sick man… I’m a malicious man. An unattractive man, I am. I think I’ve got something wrong with my liver. Still, I know damn an about my sickness and don’t know for sure what it is I’ve got something wrong with. I’m not having treatment and never have had treatment, though I do respect medical science and doctors. What’s more, I’m superstitious in the extreme too; well, enough at least to respect medical science. (I’m sufficiently educated not to be superstitious, but superstitious I am.) No, sirs, it’s out of malice I don’t want to have treatment. Now you probably won’t deign to understand that. Well, sirs, but I do understand. It stands to reason, won’t be able to explain to you precisely who it is I’ll be spiting with my malice in this instance; I know perfectly well that by riot having their treatment I won’t be able to ‘do the dirty’ in any way even on the doctors; I know better than anyone that I’ll harm just myself alone by all this and no one else. But all the same, if I’m not having treatment, then it’s out of malice. I’ve got something wrong with my liver, so let there go and be something even worse wrong with it!

Who is Ronald Wilks?

Penguin Random House says, “Ronald Wilks studied Russian language and literature at Trinity College, Cambridge, after training as a Naval interpreter, and later Russian literature at London University, where he received his PhD in 1972.”

Among his translations from Russian to English are works by Gorky, Saltykov-Shchedrin, Tolstoy, and many works by Chekhov.

About the Wilks translation of Notes from Underground

Title of book: Notes from Underground and The Double

Contains: “Notes from Underground” and “The Double”

Also includes a brief bio of Dostoevsky, a 39-page introduction by Robert Louis Jackson titled “Vision in Darkness”, a (one-sentence) note on the text, a table of ranks, endnotes, a chronology, and a list for further reading.

This translation uses British spelling.

Extract from the Wilks translation of Notes from Underground

First ~500 words of Chapter 1:

I’m a sick man . . . I’m a spiteful man. I’m an unattractive man. I think there’s something wrong with my liver. But I understand damn all about my illness and I can’t say for certain which part of me is affected. I’m not receiving treatment for it and never have, although I do respect medicine and doctors. What’s more, l’m still extremely superstitious — well, sufficiently to respect medicine. (I’m educated enough not to be superstitious, but I am superstitious.) Oh no, I’m refusing treatment out of spite. That’s something you probably can’t bring yourselves to understand. Well, I understand it. Of course, in this case I can’t explain exactly to you whom I’m trying to harm by my spite. I realize perfectly well that I cannot ‘besmirch’ the doctors by not consulting them. I know better than anyone that by all this I’m harming no one but myself. All the same, if I refuse to have treatment it’s out of spite. So, if my liver hurts, let it hurt even more!

I’ve been living like this for a long time — about twenty years. I’m forty now. I used to work in a government department, but I don’t work there any more. I was a spiteful civil servant. I was rude and enjoyed being rude. You see, I never took bribes, so I had to compensate myself in some way. (That’s a rotten joke, but I don’t intend striking it out. I wrote it down thinking it would come across very witty, but now that I’ve seen that I only wanted to do a spot of vulgar bragging I shall let it stand on purpose!) Whenever people came with their petitions to the desk where I sat I would snarl at them and I felt inexhaustible pleasure whenever I succeeded in upsetting someone. And I was nearly always successful. For the most part they were a timid bunch — we all know what people asking for favours are like. but among those fops there was one particular officer whom I just couldn’t stand. He simply wouldn’t be brought to heel and had a nasty way of rattling his sabre. For eighteen months he and I waged war over that sabre. In the end I triumphed. He stopped the rattling. However, this happened when I was still young. And do you know, gentlemen, what was the main point of my malice? Well, the main point, indeed the crowning nastiness, was that even during my most splenetic moments I was constantly, shamefully, aware that not only was I not seething with spite but that I wasn’t even embittered, and was merely scaring sparrows in vain, for my own amusement. I might foam at the mouth, but just bring me some kind of toy, give me a cup of tea with sugar and most likely I’d calm down or even be deeply touched, although I’d be so ashamed. I would most certainly grumble at myself afterwards and suffer from insomnia for several months. I’ve always been like that.

Get the Penguin Classics Wilks translation of Notes from Underground

Notes from Underground and the Double. Introduction by Robert Louis Jackson.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780140455120, 352 pages).

Get the Penguin Classics Wilks translation of Notes from Underground

Notes from Underground and the Double. Introduction by Robert Louis Jackson.

Available as an ebook (ISBN 9780141904092).

Who was Boris Jakim?

The publisher says: “Boris Jakim (1949–2024) was renowned for his translations of Russian religious thought into English. His published translations include works by Fyodor Dostoevsky, Sergius Bulgakov, Pavel Florensky, and Vladimir Solovyov.”

About the Jakim translation of Notes from Underground

Title of book: Notes from Underground

Contains: Notes from Underground

Includes a 17-page introduction by Robert Bird with suggestions for further reading, explanatory footnotes, and a translator’s preface.

Probably uses American spelling.

From the translator’s preface:

“Let me caution the reader: This translation uses coarser language than any previous one. In fact, I use a well-known four-letter word which I hope does not offend readers…. When [Notes from Underground] was first published (in 1864), the book as — philosophically and even terminologically — shocking, and my use of a four-letter word is an effort to regain some of the book’s original shock value, thus producing a fresh translation for our ruder times.”

Extract from the Jakim translation of Notes from Underground

First ~500 words of Chapter 1 (from Amazon):

I’m a sick man. . . . I’m an evil man. I’m an unattractive man. I think my liver is sick; it hurts. But I really don’t understand squat about my sickness, and I’m not sure what hurts inside me. I’m not being treated, and have never been treated, even though I have respect for medicine and doctors. I’m also extremely superstitions—in fact, so superstitious that I even have respect for medicine. (I’m sufficiently educated not to be superstitious, but I am superstitious.) No, gentlemen, it’s because I’m evil that I don’t want to receive treatment. You, on your part, probably can’t understand this. Well, sir, I understand it. Of course, I wouldn’t be able to explain to you who exactly I’m trying to annoy by being evil; I know perfectly well that the doctors don’t give a shit if I’m refusing their treatment; I know better than anyone that all this is hurting only me, nobody else. Nevertheless, if I’m not seeking treatment, it’s because I’m evil and angry. My liver is sick and it hurts—well, let it hurt even more!

I’ve been living this way for a long time—for about twenty years. I’m forty years old now I used to work in the civil service, but I no longer do. I was an evil and angry official. I was rude, and found pleasure in rudeness. After all, since I didn’t take bribes, I had to reward myself in some other way. (A lame joke; but I won’t cross it out. When I wrote it, I thought it would be very witty; but now when I see that I wrote it because I wanted to engage in a kind of vile swagger—I won’t cross it out on purpose!) When petitioners would approach my desk for information I’d gnash my teeth at them, and feel an insatiable pleasure if I succeeded in disappointing someone. And I almost always succeeded. For the most part these were timid people—petitioners, after all. But among the dandies there was a certain officer I particularly couldn’t stand. He absolutely didn’t want to submit to me, but instead would bang his saber in the most repulsive way. For a year and a half, he and I fought a war over this saber. And I finally prevailed. He stopped banging it. However, all this happened when I was still young. But do you know, gentlemen, what constituted the crux of my anger? The whole point of it, the really vile thing was that, every moment, even at those moments when I could taste the bitterest bile rising up in me, I was shamefully conscious that not only was I not angry on this occasion, but that I’m not even a fundamentally angry man, that I was only uselessly scaring sparrows and finding consolation in that. I could be foaming at the mouth, but if you were to bring me some little doll, or some tea with sugar, I might calm down and my heart might even be touched, although later I would probably gnash my teeth at myself and, out of shame, suffer from sleeplessness for a few months. Such is my custom.

Get the Eerdmans Jakim translation of Notes from Underground

Includes an introduction by Robert Bird and a translator's preface.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780802845702, 152 pages).

Get the Eerdmans Jakim translation of Notes from Underground

Includes an introduction by Robert Bird and a translator's preface.

Available as an ebook (ISBN 9781467438308).

Who are Kyril Zinovieff and Jenny Hughes?

» Bio of Kyril Zinovieff at Alma Books

» Bio of Jenny Hughes at Alma Books

About the Zinovieff and Hughes translation of Notes from Underground

Title of book: Notes from Underground

Contains: Notes from Underground

Also contains an introduction, a translators’ note, a note on the text, endnotes, extra material on Dostoevsky’s life and works, and a select bibliography.

Probably uses British spelling.

“Notes from Underground In English” by Ira Nadel

“The annotations which follow the text proper (116 –120) are helpful but not extensive…. The so-called ‘Extra Material‘ at the end of the edition includes a detailed and extensive twelve-page biography, and a separate eleven-page commentary on Dostoevsky’s works…. After these critical comments is a one-page selected bibliography with ten titles and then the opening of Notes reprinted in Russian (149 –151). ”

Extract from the Zinovieff and Hughes translation of Notes from Underground

First ~500 words of Chapter 1 (from Alma):

I ’m a sick man… a spiteful man… an unattractive man, that’s what I am. I suspect there’s something wrong with my liver. But I don’t understand a damn thing about my illness, nor do I know for sure what’s wrong with me. I’m not being treated for anything and never have been, though I respect doctors and medical science. Besides, I’m extremely superstitious, at least enough to have respect for medicine. (I’m sufficiently educated not to be superstitious, but I am superstitious.) It’s because I’m spiteful that I don’t want to have any treatment. Now that’s something you’re probably not inclined to understand. Alright, but I do understand it. I couldn’t of course explain to you who it is that I will actually hurt by my spite; I know perfectly well that I would be quite unable to foul things up for the doctors by not being treated by them; I’m aware, no one more so, that all this will harm only myself and nobody else. All the same, if I’m not being treated, it’s entirely out of spite. There’s something wrong with my liver – well, let it get worse!

I’ve been living like this for a long time – about twenty years. I’m forty now. I used to work in the Civil Service, but I don’t any more. I was a spiteful civil servant. I was rude and took pleasure in being rude. I never accepted bribes, you know, so I had to find some other reward even if it was only that. (A bad joke. But I won’t cross it out. I wrote it because I thought it would be very witty. Now that I see I wanted to show off horribly, I deliberately won’t cross it out.) When, occasionally, people came up to my table to ask for information, I used to snarl at them and was delighted every time I succeeded in upsetting them. I almost invariably succeeded. For the most part they were timid people. Of course – they were petitioners. Among the swankier lot, there was one army officer I particularly detested. He simply refused to do what he was told and rattled his sword in a disgusting way. I waged war on him about that sword for a year and a half and got the better of him in the end. He stopped rattling.

Anyway, that happened when I was young. But do you know, gentlemen, the real point about my spite – that is, the essence of it, the most revolting aspect of it? It was that I was shamefully aware, even at my most bilious, that I was not only not a spiteful, or even an embittered man, but was merely frightening sparrows to no purpose and doing it just for fun. I might be foaming at the mouth – but you bring me some little toy, give me a cup of tea with a touch of sugar in it, and I’ll calm down, even be deeply touched – though later I’ll probably be snarling at myself and, out of shame, suffering insomnia for months. That’s the way I behave, after all.

Get the Alma Classics Zinovieff and Hughes translation of Notes from Underground

Includes an introduction, translators' note, note on the text, endnotes, extra material about Dostoevsky's life and works, and a select bibliography.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9781847493743, 160 pages).

Who is Natasha Randall?

“Natasha Randall is a writer and literary translator. Her translations include We by Yevgeny Zamyatin and A Hero of Our Time by Mikhail Lermontov. Her writing has appeared in the Times Literary Supplement, New York Times, Los Angeles Book Review and more.”

About the Randall translation of Notes from Underground

Title of book: Notes from Underground

Contains: Notes from Underground

Includes an introduction by DBC Pierre.

This translation probably uses British spelling.

Extract from the Randall translation of Notes from Underground

First ~500 words of Chapter 1 (from Amazon):

I am a sick person . . . A spiteful one. An unattractive person, too. I think my liver is diseased. But I don’t give a damn about my disease and in fact I don’t even know what’s wrong with me. I do not seek treatment and have never sought treatment, though I respect medicine and doctors. Furthermore, I am superstitious to an extreme — well, only enough to respect medicine. (I am sufficiently educated that I shouldn’t be superstitious, but I am superstitious.) No, sir, I won’t seek treatment out of spite. And this, I supposed, you won’t deign to understand. Well, sir, I do understand it. Of course, in this case, I won’t be able to explain it to you, whom I season with my spite. I know perfectly well that I cannot ‘befoul’ the doctors with the fact that I’m not being treated by them; I know better than anyone that I am only harming myself with all this, and no one else. But nonetheless, if I do not seek treatment, it is out of spite. My little old liver is diseased — and may it be even more severely diseased!