“Which English translation of Gargantua and Pantagruel should I read?”

An episodic, picaresque masterpiece written in French by Renaissance humanist François Rabelais, Gargantua and Pantagruel was originally published as a series of five volumes:

- 1532 – Pantagruel

- 1534 – Gargantua

- 1546 – Le Tiers Livre (“The Third Book”)

- 1552 – Le Quart Livre (“The Fourth Book”)

- 1564 – Le Cinquième Livre (“The Fifth Book”)

The true authorship of the fifth book, published after the death of Rabelais in 1553, is uncertain.

Gargantua now appears first in some reprintings, as the events in it concern Pantagruel’s father and come chronologically before the events in all four other volumes.

Sometimes published under a title like “The Works of Rabelais,” the story itself may be called something like “The Five Books of the Lives, Heroic Deeds and Sayings of Gargantua and His Son Pantagruel.”

Gargantua and Pantagruel: Translations in English

- 1653/1694 – Thomas Urquhart and Peter Anthony Motteux (public domain)

- 1893 – William Francis Smith (mostly complete)

- 1929 – Samuel Putnam

- 1936 – Jacques Leclercq

- 1955 – J. M. Cohen

- 1990 – Burton Raffel (Norton)

- 1991 – Donald M. Frame (University of California)

- 2003/2018 – Andrew Brown (Alma, first two volumes only)

- 2006 – Michael Andrew Screech (Penguin)

Gargantua and Pantagruel: What’s the oldest English translation?

The works of François Rabelais, 1897 edition, introduction and revision by Alfred Wallis

The first known English translation appeared 100 years after the original. There may have been an earlier translation, but if so, it’s lost: “It is not easy to determine the precise date of the first translation of Rabelais into English. Certain entries in the Registers of the Stationers’ Company indicate a period between 1592 and 1594; but not even the fragment of a sixteenth century edition has survived to our own day. It is certain that Shakespeare and Ben Jonson, amongst the Elizabethan dramatists, were cognizant of the name and attributes of the famous giant Gargantua; but whether from actual knowledge or merely from hearsay cannot now be determined.”

Gargantua and Pantagruel: High on the Scale of Untranslatability

Oxford Guide to Literature in English Translation: “Renaissance Prose: Rabelais and Montaigne” by Peter France

The “carnivalesque variety of language, where many voices and speech types jostle in a polyphony which may or may not offer a serious ‘message’, offers a notable challenge to the translator.”

From the translator’s introduction by Floyd Gray to Selections from Gargantua and Pantagruel:

“A translator is faced with so many problems—especially a translator of Rabelais. So much that is characteristic of his genius depends upon verbal creation and semantic confusion that a translation can be little more than an approximation.”

From the note on the translation by M.A. Screech:

“Rabelais deliberately employs many rare words, words which would have baffled most of his contemporaries. That is a conscious stylistic device. His vocabulary is vast…. Some of his words should fox readers and others challenge them. Their very rarity is their appeal…. Rabelais uses more different words than any other French author…. Rabelais enjoys punning and elaborately playing with words…. Plays on words rarely pass easily from one tongue to another, yet they must be rendered.”

Timothy Hampton: “Phrasebook: Thinking About Translation in Rabelais”

This page compares the translations offered by Urquhart, Raffel, Cohen, and Screech of a famously crude scene where one character attempts to engage in wordplay with another. The example highlights the difficulties in translating word-based humor.

Gargantua and Pantagruel: Translation Comparison

Extracts have been included in plain text so that you can easily compare how the different translators sound.

Gargantua and Pantagruel: TL;DR

If you just want a quick and dirty recommendation, jump to the conclusion.

Publication history of the Urquhart and Motteux translation of Gargantua and Pantagruel

1653 – Urquhart published Books 1 and 2

1660 – Urquhart died, leaving behind an unpublished translation of Book 3

1693 – Motteux published his version of Urquhart’s Book 3

1694 – Motteux published his version of Urquhart’s Books 1, 2 and 3 with his own new translations of Books 4 and 5, in five separate volumes

1708 – Motteux published his version in two volumes, with a preface

1737 – John Ozell published an edited complete version of the Urquhart/Motteux translation; some text removed by Motteux was restored, copious notes were added (translations of notes from Jacob Duchat’s 1711 critical edition in French)

1897 – Alfred Wallis published another edited version, with the same text but fewer notes

1929 – Albert Jay Nock and Catherine R. Wilson produced a modernized edition

Who was Thomas Urquhart?

Sir Thomas Urquhart of Cromartie, Knight, was a Scottish writer and translator best known for his translation of Rabelais. He had a verbose and elaborate writing style and liked to make up new words.

The Scotsman: The curious case of Thomas Urquhart

“He published a book in 1645 called Trissotetras, Or A Most Exquisite Table For Resolving Triangles, which boasted that a student could learn a year’s worth of mathematical formulae in seven weeks by using his method. It is such a cryptic and strange book its significance in his story has been overlooked. Mathematicians tend to read it for the mathematics, and have concurred that ‘it is not absolute nonsense, but it is written in a most unintelligible way’.”

Who was Peter Anthony Motteux?

Peter Anthony Motteux, born Pierre Antoine Le Motteux in France, was an English author, editor, playwright, and translator. His name is sometimes printed as Motteaux. He produced an important and long-lived but much maligned translation of Don Quixote from Spanish to English. He died in obscure circumstances.

Who was John Ozell?

John Ozell was an accountant and a reputedly mediocre translator. He learned French, Italian, Spanish, Latin and Greek and translated a lot of plays. According to translator W.F. Smith, he was a friend of Motteux. He also revised Motteux’s translation of Don Quixote.

Dictionary of National Biography: John Ozell by Thomas Seccombe

“Chalmers significantly says, ‘it was his misfortune to undertake works of humour and fancy, which were qualities he seemed not to possess himself, and therefore could not do justice to in others.’ “

The lives of the poets of Great Britain and Ireland: John Ozell

“Mr. Ozell, who, if he did not possess any genius, has not yet lived in vain, for he has rendered into English some very useful pieces, and if his translations are not elegant; they are generally pretty just, and true to their original…. He possibly possessed a large share of good nature, which, when joined with but a tolerable understanding, will render the person, who is blessed with it, more amiable, than the most flashy wit, and the highest genius without it.”

About the Urquhart and Motteux translation of Gargantua and Pantagruel

Virginia Quarterly Review: “Rabelais in English” by Francis H. Abbott

“The English-speaking peoples have long been fortunate in possessing a translation of Rabelais that is itself a classic of English prose. Urquhart’s “fidelity” consists not in a literal rendering, but in making an impression upon the English reader corresponding to that the original makes upon a French one. In this respect, only the King James version of the Bible is equal to it and these two translations remain unapproached in our language.”

The Scotsman: “The Curious Case of Thomas Urquhart”

“There are very few books where the translator is as important as the author – books like Pope’s Iliad, Dryden’s Aeneid or Fitzgerald’s Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. Scots have produced a staggering amount – Muir’s Kafka, Scott-Montcrieff’s Proust – but towering above them all is Urquhart’s Rabelais. For a book all about exaggeration, it is the best tribute to write an over-the-top translation. For one thing, it’s 70,000 words longer than the original.”

From the introduction by Alfred Wallis to The Works of François Rabelais, 1897

“There is happily no necessity, at the close of this century of progress and enlightenment, to preface a new edition of the Works of Doctor Francois Rabelais (calling himself anagrammatically Monsieur Alcofribas Nasier) with an apology for printing it. If such an apology were needed, the statement that the translation used in these volumes has been, in one form or another, before the English-reading public for upwards of two centuries would be deemed by most people (it is known to have influenced the decision of one of our most eminent judges in favor of Rabelais considered as an English classic) a sufficient defence against possible attacks from the professional puritan.”

Gargantua and Pantagruel, Introduction by Charles Whibley, 1900

From the introduction to volume 1 (volume 24 of The Tudor Translations): “

“[Urquhart’s translation] can scarcely be called a translation at all; rather it is the English Rabelais. That Urquhart made mistakes is obvious: now he did not understand his author’s meaning; now an obstinate love of elaboration caused him to annotate his author rather than to translate him…. By knowledge as by temperament, he was perfectly fitted for his task. French and English were both foreign tongues to him, and he knew them equally well…. [H]e was, in a sense, Rabelais reincarnate: yet Rabelais with his humour obscured by pedantry and his trick of ridicule turned to seriousness…. [Y]ou read Urquhart with no thought of translation. Surely it is an original that you hold in your hand, with its perfect sense of narrative and its accurate echo of a complicated phrase!”

Gargantua and Pantagruel, Introduction by Charles Whibley, 1900

From the introduction to volume 3 (volume 26 of the Tudor Translations, Fourth and Fifth Books of the novel): “To turn from Urquhart to Motteux is to travel at a page from the old world to the new…. The sense of Rabelais is followed yet more closely in the books of Motteux’s translating, but the full humour of the original is attenuated to the taste of a feebler epoch…. [Motteux] rattles on with little enough respect for the author he translates, or for the language which he has adopted. But his very faults of style and taste give him an interest of curiosity; and, foreigner though he was, he also played his part in the development of our tongue…. He was, in fact, nothing better (nor worse) than an adroit and busy hack. He wrote plays, he composed poems, he translated Rabelais and Cervantes…. Dryden and Steele cherished a constant affection for him, praising him with the indiscreet eloquence of friendship, and setting him on a pinnacle of eminence where he could not long expect to keep a foothold. Pope, on the other hand, denounced him with all the vigour and venom which he reserved for the second-rate, and honoured him after his death with a place in the Dunciad…. [T]hough he pilfers Urquhart’s vocabulary, he cannot emulate his style…. None the less, his version has very solid merits of its own. Though it lacks dignity, it is always near the original, and when there is no chance of embroidery you may find passages which are no unworthy echo of the original prose…. [H]is is the version of the Fourth and Fifth Books which will represent Rabelais in English for all time. It may be edited: it is not likely to be superseded. For it is nearer to the French than even Urquhart’s masterpiece in all save spirit; and, while it fills us with a profound regret that Urquhart never finished the task appropriated to him by his genius, we may still thank this amiable, familiar Frenchman for doing after his guise what none else has done better.”

Rabelais in English Literature by Huntington Brown, 1933

“[Urquhart’s] translation was, in spite of its departures from the letter, which the critics have faithfully noted, an ideal one. In it Rabelais lives again, for it represents the wedding of the genius of the Master to a technique no whit inferior to his own…. Urquhart frequently retains French expressions in his text. Sometimes, as in the case of puns, he has no other course…. There is no consistency in his practice, for he sometimes translates words which one might expect he would have retained…. There is a slight taint of Gallicism in his proverbs, which he sometimes translates literally rather than logically…. It must be allowed, however, that such ‘transliterated’ proverbs have a flavor all their own, which may have been nicely calculated.”

Rabelais in English Literature by Huntington Brown, 1933

“The best known accounts of Motteux’s translation are probably those of Charles Whibley. Whibley is very hard on him…. Whibley’s view is incontrovertible as far as it goes, but I believe that it overemphasizes the shortcomings and understates the merits of a translation which at best is the equal, and as a whole but little the inferior of that of Urquhart.”

Oxford Guide to Literature in English Translation: “Renaissance Prose: Rabelais and Montaigne” by Peter France

“Urquhart’s rendering is rich, inaccurate, at times barely comprehensible. It is oddly literal, sometimes virtually transcribing the definitions in Cotgrave’s 1611 French-English dictionary…. Motteux makes fewer mistakes than Urquhart over Rabelais’s meaning. At the same time, he is freer and less respectful…. Nevertheless his version has life and has acquired a firm place as the continuation of the greater Urquhart.”

From the translator’s introduction by Samuel Putnam:

“As for the reader who is acquainted with Rabelais only through the medium of an English translation, he in the past has been in a peculiar position, which has led to his forming a picture of the author that is often almost wholly false, or in any event, nearly always, a distorted one…. That Sir Thomas [Urquhart] was a creative genius in his own right, no one, probably, would deny. He deserves a place in any history of our literature, and especially in any account of our prose. If this place is not commonly accorded him, it is doubtless for the reason that he is looked upon as a translator rather than a creator, whereas the truth of the matter is that he is too much the creator to be able to subordinate himself in a manner that is entirely satisfactory always to the task of carrying over the thought and expression of another. There is in him much, very much, of Rabelais’ own lust for life and language, of the Rabelaisian atmosphere and effect; yet when all is said, the resulting product is Urquhart rather than Rabelais…. Sir Thomas himself was unfamiliar with many of the allusions in his author which have only been cleared up by late-nineteenth- and twentieth-century scholars…. As a consequence, in order to cover up his ignorance of the real-life context or his uncertainty as to the meaning involved, Urquhart very often improvises, expands, and embroiders upon the text, dumping into it upon occasion all the synonyms for French word that he has found in his Cotgrave [French-English Dictionary].”

From the translator’s preface by W.F. Smith:

“The excellence of Urquhart and Motteux’ translation is generally acknowledged, and a new one would have been unnecessary had the rendering been even. Urquhart’s work in the first two Books is much the best, and occasionally Motteux in the later Books reaches that level, but not unfrequently these translators betray an inclination to amplify unnecessarily…. Speaking generally, Motteux is much more diffuse than Urquhart, and seems to shew a pride in parading his knowledge of the strong proverbial English expressions of which he had so wonderful a mastery.”

From the translator’s introduction by J.M. Cohen in the Penguin edition:

“[Urquhart’s] version, completed by Motteux, is far from literal. In fact it often seems more like a brilliant recasting and expansion than a translation. This applies only to Sir Thomas Urquhart’s own work. Motteux’s version of the Fourth and Fifth Books is no better than competent hackwork. Like Urquhart, he frequently departs from his original. But where Urquhart often enriches, he invariably impoverishes.

From the translator’s preface by John Cowper Powys:

“Sir Thomas Urquhart is not a fellow-spirit with Rabelais; and the fact that he was so vigorous and headstrong a genius on his own account is precisely what did the mischief. Like other egotistical admirers of a thing to which they lack the essential clue the Laird of Cromarty not unfrequently gets in the way; comes to stand, in fact, between us and the master. And he has a special tendency to do this when the master begins to speak in that subtle, airy tone so peculiar to the French language.”

From the translator’s note by Donald M. Frame:

“I found Sir Thomas Urquhart… savory and picturesque but too much Urquhart and at times too little R; too often the reader must guess whom he is reading, author or translator. I have borrowed some succulent phrases (especially oaths and insults) gratefully but been wary of the sense in the Urquhart.”

Extract from the Urquhart and Motteux version of Gargantua and Pantagruel

I must refer you to the great chronicle of Pantagruel for the knowledge of that genealogy and antiquity of race by which Gargantua is come unto us. In it you may understand more at large how the giants were born in this world, and how from them by a direct line issued Gargantua, the father of Pantagruel: and do not take it ill, if for this time I pass by it, although the subject be such, that the oftener it were remembered, the more it would please your worshipful Seniorias; according to which you have the authority of Plato in Philebo and Gorgias: and of Flaccus, who says that there are some kinds of purposes (such as these are without doubt), which, the frequentlier they be repeated, still prove the more delectable.

Would to God everyone had as certain knowledge of his genealogy since the time of the ark of Noah until this age. I think many are at this day emperors, kings, dukes, princes, and popes on the earth, whose extraction is from some porters and pardon-pedlars; as, on the contrary, many are now poor wandering beggars, wretched and miserable, who are descended of the blood and lineage of great kings and emperors, occasioned, as I conceive it, by the transport and revolution of kingdoms and empires, from the Assyrians to the Medes, from the Medes to the Persians, from the Persians to the Macedonians, from the Macedonians to the Romans, from the Romans to the Greeks, from the Greeks to the French.

And to give you some hint concerning myself, who speaks unto you, I cannot think but I am come of the race of some rich king or prince in former times: for never yet saw you any man that had a greater desire to be a king, and to be rich, than I have, and that only that I may make good cheer, do nothing, nor care for anything, and plentifully enrich my friends, and all honest and learned men. But herein do I comfort myself, that in the other world I shall be so, yea and greater too than at this present I dare wish. As for you, with the same or a better conceit consolate yourselves in your distresses, and drink fresh if you can come by it.

Get the Everyman's Library Urquhart and Motteux translation of The Works of Rabelais

Title: Gargantua and Pantagruel. Includes an introduction by Terence Cave.

Available as a hardcover (ISBN 9780679431374, 872 pages).

Get the Dover Urquhart and Motteux translation of The Works of Rabelais

Title: Gargantua and Pantagruel. Starts with Gargantua.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780486808338, 816 pages).

Get the Dover Urquhart and Motteux translation of The Works of Rabelais

Title: Gargantua and Pantagruel. Starts with Gargantua.

Available as an ebook (ISBN 9780486820798, 816 pages).

Get the CGR Publishing Restoration Workshop Urquhart and Motteux translation of The Works of Rabelais

Title: The Works of Rabelais: Gustave Doré Restored Special Edition. Starts with Gargantua. 7"x10" pages, 50 illustrations by Gustave Dore, facsimile typeset pages.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9781592181599, 708 pages).

Get the Delphi Classics Urquhart and Motteux translation of The Works of Rabelais

Title: Francois Rabelais: Complete Works. Contains some of Gustave Dore's illustrations and a handful of critical essays.

Available as an ebook.

Get the Gutenberg Urquhart and Motteux translation of The Works of Rabelais

Title: Gargantua and Pantagruel. Also, "Five books of the lives, heroic deeds and sayings of Gargantua and his son Pantagruel". Illustrations by Gustave Dore. “The text of the first Two Books of Rabelais has been reprinted from the first edition (1653) of Urquhart’s translation… Urquhart’s translation of Book III appeared posthumously in 1693, with a new edition of Books I and II, under Motteux’s editorship. Motteux’s rendering of Books IV and V followed in 1708. Occasionally (as the footnotes indicate) passages omitted by Motteux have been restored from the 1738 copy edited by Ozell.” Starts with Gargantua.

Available as a FREE ebook.

About the Smith translation of Gargantua and Pantagruel

The full title is: Rabelais: The Five Books and Minor Writings together with Letters and Documents Illustrating His Life.

Oxford Guide to Literature in English Translation: “Renaissance Prose: Rabelais and Montaigne” by Peter France

Regarding W.F. Smith’s translation: It is “an example of what has been called the Victorian Tudor style” and is “highly literal, archaizing” and “well-annotated” and “leaves some ‘offensive’ chapters (e.g. Gargantua, 13) in the original French.”

François Rabelais by Arthur Tilley, 1907

“The translation, which is far more faithful than Urquhart’s, is excellent, and the notes are helpful and judicious.”

From the extensive translator’s preface by W.F. Smith:

“This edition incorporates the notes of Duchat, some from Motteux, De Marsy and others, besides giving original notes on antiquarian, linguistic and other subjects, as well as a voluminous historical commentary…. As to the translation itself, although it has been made independently, it has been made with Urquhart lying open and compared paragraph by paragraph. Without hesitation a happy turn or rare word has been adopted from the old rendering. Often it was curious to note how the translations of a paragraph would prove almost identical word for word, till a closer examination of the text shewed that there could hardly be any variation in a faithful version…. With regard to a plan which has been adopted in this translation, of leaving some five chapters in the original French, exception may be taken. In a book which must contain the whole in some form, it is a question whether a very small portion may not well be left untranslated when the matter is too offensive, especially when the romance is in no wise helped forward by these chapters. An obvious objection is that, by leaving them in the French, special attention is drawn to what is desirable should pass without notice…. This objection would be of weight if the present translation were likely to fall into the hands of schoolboys. As it is intended for readers who would neither be scandalized nor allured by such a quasi-omission, it may well be that the notes appended to these chapters will be all they will care to see of them…. As it is, much had to be written from which one’s feelings and pen recoiled, and it is hoped that a repugnance to put into English certain most undesirable matter may not be judged hardly.”

From the translator’s introduction by J.M. Cohen in the Penguin edition:

“Smith’s version of 1893 is a painfully exact exercise in the Victorian Tudor style, valuable, however for its excellent battery of notes…. Smith’s Rabelais deserves to stand on the shelf beside H. E. Watts’s Don Quixote as a monument of excellent scholarship devoted to a faulty theory of translation.”

From the translator’s preface by John Cowper Powys:

“I do not think any imaginative person could read very far in either of these versions [Smith and Putnam] without feeling that what he was reading represented long and devoted labour.… But even though both these versions display the same unwearied devotion, the same intensive research, the same unqualified personal relish, they reveal these qualities in opposite ways, the former [Smith] following scrupulously our orthodox English traditions, the latter [Putnam] boldly launching forth into a challenging and exciting experiment in translation…. In the case of W. F. Smith’s two noble volumes my chief complaint is the absurdly superficial one that I find his old-time use of capital letters a little trying. But I do feel seriously indignant with him for denying [us] practically the whole of the significant last chapter of the Fourth Book, which in my view is the author’s final word to posterity…. [T]here is something in this excellent translation a little too… stately, courtly, and refined, something that errs… by a too cautious conservatism.”

From the translator’s note by Donald M. Frame:

“W.F. Smith… was an excellent scholar; but he shuns R’s obscenities and lacks his raciness.”

Extract from the Smith version of Gargantua and Pantagruel

I refer you to the Grand Pantagrueline Chronicle1 for the Knowledge of the Genealogy and Antiquity whence Gargantua is descended unto us. Therein you will understand more at length how the Giants were born in this World, and how from them by direct Line issued Gargantua, Father of Pantagruel, and it shall not misplease you if for the present I pass it over, although the Matter be such, that the more it should be remembered the more it would please your Lordships; for which you have the authority of * Plato in Philebo et Gorgia, and also of b Flaccus, who says that there are certain Subjects (without doubt such as this) which are the more delectable the oftener they are repeated.

Would to God that every one had as certain Knowledge of his Genealogy from Noah’s Ark up to the present Age. I think there be many this day who are Emperors, Kings, Dukes, Princes and Popes on the Earth who are descended from some Carriers of Indulgences and Faggots; 2 as on the contrary many are Beggars from Door to Door, suffering poor Wretches, who are descended from the Blood and Lineage of great Kings and Emperors,3 when we consider the wonderful Transference of Kingdoms and Empires:

From the Assyrians to the Medes,

From the Medes to the Persians,

From the Persians to the Macedonians,

From the Macedonians to the Romans,

From the Romans to the Greeks,

From the Greeks to the French.

And to give you to understand concerning myself, who am speaking to you, I fully believe that I am descended from some rich King or Prince in times of yore; for never did you see a man who had a greater Desire to be a King and to be rich than I, to the end that I may make good Cheer, do no Work, trouble myself not a whit, and plentifully enrich my Friends and people of Worth and of Knowledge: but herein do I comfort myself that in the other c World I shall be all this, nay greater than at present I dare to wish. Do you then in such, or a better, Belief take Comfort in your Misfortunes and drink lustily, if it can be done.

Get the Hathi Trust Smith translation of Rabelais

Title: Rabelais: The Five Books and Minor Writings togehter with Letters & Documents Illustrating His Life. Includes a translator’s preface, some pages on the English translators of Rabelais, a summary of the life and writings of Rabelais, a chronological summary of events in the form of a chart, a bibliography of the first three books, and a map of Chinonais. Text contains footnotes. Starts with Gargantua.

Available as a FREE ebook.

Who was Samuel Putnam?

Samuel Putnam was an American scholar and translator. He is best known for his translation of Don Quixote.

About the Putnam version of Gargantua and Pantagruel

The commonly available 1946 “Portable Rabelais” is not a complete translation, but a selection of passages. However, a complete translation was made and published as well.

“All the Extant Works of Francois Rabelais: An American Translation With a Critical Text Variant Readings” was a limited edition of 1,300 copies in three volumes, illustrated by Jean de Bosschere and printed privately for subscribers by Covici Friede Publishers in 1929. It contains the unabridged translation of Samuel Putnam. Several second-hand copies are available:

The abridged “Portable Rabelais” is out of print but available second-hand:

From the translator’s introduction by Samuel Putnam:

“In the selection of the passages contained in this volume, the primary purpose has been to present a coherent picture of Rabelais the writer and Rabelais the thinker—in other words, a picture of the author’s mind as revealed in his creative work. All the best known portions of the Gargantua and Pantagruel, those commonly regarded as being most characteristically “Rabelaisian,” will be found here, along with others which are ordinarily looked but which are important for the light they have to throw on Maitre Francois’ intellectual attitudes and development. The posthumous Fifth Book is not represented.”

From the translator’s introduction by Samuel Putnam:

“In this version the endeavor of the editor-translator will be to let the man and his mind speak for themselves through as faithful as possible a presentation of Rabelais’ writings, based upon a critical study of the various texts as revised by the author and with such, and only so much, commentary as may be needed to render the text comprehensible to the present-day reader…. As for the translation itself, there has been no attempt at an unduly modernized version; but rather, an effort has been made to preserve a judicious balance between the old and the new in language, by avoiding on the one hand unnecessary archaisms employed merely for the sake of effect, and on the other hand, contemporary English or American expressions that would be out of place and would jar upon the reader. It is, as may be imagined, not an easy balance to maintain….In any event, there would seem to be no point in undertaking to rewrite Urquhart…. What is one to do where there are so many allusions that call for an explanation? Write the notes into the text? That seems hardly fair to the author, since it not only puts into his mouth things that he did not say and possibly never would have said, but also spoils the rhythm of the original. There appeared to be nothing for it but to hold the notes down to a minimum and place them at the end of each chapter.”

From the translator’s preface by John Cowper Powys:

“I do not think any imaginative person could read very far in either of these versions [Smith and Putnam] without feeling that what he was reading represented long and devoted labour.… But even though both these versions display the same unwearied devotion, the same intensive research, the same unqualified personal relish, they reveal these qualities in opposite ways, the former [Smith] following scrupulously our orthodox English traditions, the latter [Putnam] boldly launching forth into a challenging and exciting experiment in translation…. Mr. Putnam has had the audacity to treat Rabelais’ work as a living rather than a dead thing… adaptable to any age…. Mr. Putnam has certainly not forgotten that such centuries-old mother-wit as we get in Rabelais, such leisurely countryside bawdiness, such grotesque and gargoylish fantasies of farmyard grossness have their own intrinsic value, but he feels that they must be brought, as it were up to date and up to scratch.”

From the translator’s note by Donald M. Frame:

Putnam’s translation is “arguably the best we have”.

Extract from the Putnam version of Gargantua and Pantagruel

I send you back to the Great Pantagrueline Chronicle, if you would form an idea of the genealogy of Gargantua and of the antiquity from which he has come down to us. From it you will learn in full how the Giants were born into this world, and how from them, in direct line, sprang Gargantua, father of Pantagruel; and so, do not be put out with me if for the present I pass on, although the subject is such a one that the oftener it is recalled, the more pleasing it is to your Lordships, for which you have the authority of Plato in his Philebo and his Gorgias, as well as of Flaccus, who says that there are certain subjects such as these very ones, no doubt, that are the more delectable the more often they are discussed.

Would to God that every one were as certain of his genealogy from Noah’s ark down to the present day! It is my opinion that a number are today emperors, kings, dukes, princes, and popes of the earth who are descended from certain porters and pardon-peddlers, just as, on the other hand, a number are almshouse beggars, needy and miserable, who are of the blood and lineage of great kings and emperors, as a result of the marvelous passing of realms and empires:

From the Assyrians to the Medes;

From the Medes to the Persians;

From the Persians to the Macedonians;

From the Macedonians to the Romans;

From the Romans to the Greeks;

From the Greeks to the French.

And in order to give you an idea of who it is that is speaking to you, I will say that I believe that I am descended from some rich king or prince of former times, for you never saw a chap who had a greater longing to be a king, and a wealthy one, than I, so that I might be able to dispense good cheer, not have to work, not have to worry about anything at all, but be able to enrich my friends and all others who are good and wise. But in this, I comfort myself that in the other world I shall be greater than at present I should dare to hope. And with a like or a better thought, comfort your own misfortune, and drink hearty, if it can be done.

Get the Covici Friede Publishers Putnam translation of All the Extant Works of Francois Rabelais

Title: All the Extant Works of Francois Rabelais. An American Translation With a Critical Text Variant Readings, Variorum Notes & Drawings Attributed to Rabelais. With Illustrations by Jean de Bosschere. Illustrated with full-page color plates and more than 100 full-page black and white illustrations. Privately Printed for Subscribers Only. Limited to 1300 numbered copies. Top edge gilt. Published by Covici Friede Publishers, New York, 1929. Starts with Gargantua.

Available as a set of 3 hardcovers.

Who was Jacques Leclercq?

Jacques Leclercq was a Belgian who scholar and priest who studied law, philosophy, and theology.

About the Leclercq translation of Gargantua and Pantagruel

The Leclercq translation is out of print but likely available second-hand.

Oxford Guide to Literature in English Translation: “Renaissance Prose: Rabelais and Montaigne” by Peter France

Le Clercq’s translation is characterized as “incorporating explanatory material into the text and remodeling Rabelais’s sentences.”

The Ambiguities: “Translating Ancient, Humanist, and Contemporary Literature” by an unnamed librarian

“The emphasis here is on enjoyment of the work, with an introduction (by the translator, Jacques LeClercq) that devotes all of four brief paragraphs to the problems of translation and is chiefly concerned with explaining Rabelais’ life and times. LeClercq seeks ‘interest and readability.’ Astonishingly, he has done so by inserting material that would be presented as footnotes in most editions directly into the text — so that, for instance, explanations of complicated idioms and phrases in languages other than French in the original are put into the mouths of the narrator and other characters.”

From the translator’s introduction by Jacques Leclercq:

“There is the standard edition of Urquhart and LeMotteux…. I have had it… constantly open before me as I worked…. Magnificent as the Urquhart-LeMotteux is, it too, like its original, has in places become obsolete, for all the vigor of its style. It requires annotation, explanation. And it also seemed to me, perhaps rashly, that an idiom closer to modern English and closer to the critical edition of Rabelais, might be employed. In attempting this, I have not consulted either the Smith or Putnam version. Perhaps rashly, too, I have boldly incorporated into the text, explanations from the footnotes of the Critical French Edition published by Champion, as well as explanations I myself supplied…. I have striven especially for interest and readability, trusting that through these the thought and humor of Rabelais might best be communicated.”

From the translator’s preface by Burton Raffel:

“[Jacques LeClerc’s] translation is in many ways an encyclopedia in disguise.”

From the translator’s note by Donald M. Frame:

“The version of Jacques Leclercq… is brilliant but rather independent of R; Leclercq encumbers R’s text with his own notes, and often, like Urquhart, leaves the reader uncertain whom he is reading.”

Extract from the Leclercq version of Gargantua and Pantagruel

If you would learn the genealogy and antiquity which produced Gargantua, then I refer you to the lofty Chronicle of Pantagruel. Here you will learn in greater detail how giants were born in this world and how Gargantua, father to Pantagruel, descended directly from them. Do not take it amiss if, for the moment, I omit the account here, though the oftener I told the tale, the better it would please your lordships. 1 make this statement on the authority of Plato, in his Philebus and Gorgias, and of Flaccus, who declares there that certain topics (ours is undoubtedly among them) improve by repetition.

Would to God every one could be as certain of his pedigree from the days of Noah’s celebrated ark down to the present. To my way of thinking, many a man sprung from a race of sham relic-peddlers and journeymen-carriers walks the earth to-day an emperor, king, duke, prince or pope. Similarly, not a few of our sorriest, most miserable tramps are sprung from the blood and lineage of proud kings and emperors. This is due to the unbroken descent of universal monarchy from the Assyrians to the Medes, from the Medes to the Persians, from the Persians to the Macedonians, from the Macedonians to the Romans, from the Romans to the Byzantine Greeks and, finally, from the Greeks to the French.

What is more, to give you some notion of myself who now address you, I believe I derive my origin from some opulent monarch of olden days. For you never yet clapped eyes upon a man who craved kingship or wealth more passionately than I or longed more fervidly to live sumptuously, to do nothing, to avoid worry, to enrich abundantly both his friends and all other gentlemen of learning and worth. Yet I am consoled as I reflect that I shall be all this in the next world, to a vaster extent even than I dare wish to-day. For your part, if you nourish these or loftier hopes, take comfort in your distress and drink of the best, if you can manage it.

Get the Modern Library Leclercq translation of The Complete Works of Rabelais

Title: The Complete Works of Rabelais: The Five Books of Gargantua and Pantagruel. Out of print but available secondhand. Starts with Gargantua.

Available as a hardcover.

Who was J. M. Cohen?

John Michael Cohen was a British translator of works in Russian, Spanish, and French into English. He translated Don Quixote.

About the Cohen translation of Gargantua and Pantagruel

Out of print but available second-hand. Published by Penguin. Also published in a collector’s edition (either The Oxford Library of the World’s Great Books or The Franklin Library) in a leather binding with illustrations by Gustave Dore.

Oxford Guide to Literature in English Translation: “Renaissance Prose: Rabelais and Montaigne” by Peter France

J.M. Cohen “recasts the text in acceptable modern English, avoiding archaism (except for comic effect) and shortening Rabelais’s sometimes sprawling sentences. He is unembarrassed in his rendering of obscenities, and his text reads cheerfully.”

From the translator’s note by Donald M. Frame:

Cohen’s translation “although in the main sound, is marred by his ignorance of sixteenth-century French…. For much of R’s text, however, the everyday part, his resourceful experience as a translator makes him our best guide.”

From the translator’s introduction by J.M. Cohen in the Penguin edition:

“[I] have often followed the guidance of Rabelais’ scholarly Victorian translator, W.F. Smith. As for earlier translations, I am often in debt to Urquhart for a phrase.”

Extract from the Cohen version of Gargantua and Pantagruel

For knowledge of Gargantua’s genealogy and of the antiquity of his descent, I refer you to the great Pantagrueline Chronicle, from which you will learn at greater length how the giants were born into this world, and how from them by a direct line issued Gargantua, the father of Pantagruel. Do not take it amiss, therefore, if for the moment I pass this over, though it is such an attractive subject that the more often it were gone over the better it would please your lordships For which fact you have the authority of Plato in his Philebus and his Gorgias, and of Horace, who says that there are some things—and these are no doubt of that kind—that become more delightful with each repetition.

Would to God that everyone had as certain knowledge of his genealogy, from Noah’s Ark to the present age! I think there are many today among the emperors, kings, dukes, princes, and popes of this world whose ancestors were mere peddlers of pardons and firewood; as, on the contrary, there are many almshouse beggars — poor, suffering wretches—who are descended from the blood and lineage of great kings and emperors; which seems likely enough when we consider the amazing transferences of crowns and empires:

From the Assyrians to the Medes,

From the Medes to the Persians,

From the Persians to the Macedonians,

From the Macedonians to the Romans,

From the Romans to the Greeks,

From the Greeks to the French.

And to give you some information about myself, who address you believe that I am descended from some wealthy king or prince of the olden days. For you have never met a man with a greater desire to be a king or to be rich than I have, so that I may entertain liberally, do no work, have no worries, and plentifully reward my friends, as well as all worthy and learned men. But I comfort myself with one thought, that in the other world I shall be all this, and greater still than at present I dare even wish. So console yourselves in your misfortunes too, with as good thoughts or better, and drink lustily if you can get the liquor.

Get the Penguin Classics Cohen translation of The Histories of Gargantua and Pantagruel

Title: Gargantua and Pantagruel. Contains all 5 parts. This is the most recent out-of-print paperback. Probably starts with Gargantua.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780140440478, 720 pages).

Get the Penguin Classics Cohen translation of The Histories of Gargantua and Pantagruel

Title: Gargantua and Pantagruel. Contains all 5 parts. This will do a search for any out-of-print Cohen/Penguin edition going back to 1955. Probably starts with Gargantua.

Available as a paperback.

Get the Franklin Library Cohen translation of The Histories of Gargantua and Pantagruel

Title: The Histories of Gargantua and Pantagruel. Contains all 5 parts. Out-of-print edition by Franklin Library, or The Oxford Library of the World's Great Books. Dark brown faux leather covers, gilt-stamped on front, spine, rear. Two raised cords on spine. All page edges gilt. Illustrations by Frank E. Papé. Starts with Gargantua.

Available as a hardcover.

Who was Burton Raffel?

Burton Raffel was an American writer, translator, and scholar known for his translation of Beowulf. He also translated Don Quixote and Dante’s Divine Comedy.

About the Raffel translation of Gargantua and Pantagruel

Oxford Guide to Literature in English Translation: “Renaissance Prose: Rabelais and Montaigne” by Peter France

Burton Raffel’s translation “is less accurate in details; there are quite frequent misreadings, potentially obscure allusions are dropped, and explanatory or decorative phrases are added. It is, however, written in a lively and frequently inventive modern idiom, and of the modern translations [up to the year 2000] comes nearest to equaling the verve of Urquhart-Motteux.”

From the translator’s preface by Burton Raffel:

“I have tried to devise a flexible and responsive contemporary English prose equivalent, while trying at the same time to capture as much as I possibly could of the sweep and slash of Rabelais’ writing. I have worked hard to keep his long, gorgeously piled-up sentences—not always easy to follow, even in the original Middle French. Chopping him into neatly logical short sentences makes Rabelais superficially more comprehensible, but infinitely less interesting. Similarly, I have sometimes briefly and I hope unobtrusively cued the curious reader to the books, personages, and events behind Rabelais’ many erudite references, but… I have not sought to explain in detail each and every such reference. Nor have I relied on footnotes, which seem to me out of place in a work meant to be read as literature, and, as its author intended, for enjoyment as well as enlightenment. Neither, of course, have I suppressed or consciously altered anything, re-assigned speeches, or taken the other liberties so freely exercised by earlier translators.”

Extract from the Raffel version of Gargantua and Pantagruel

Let me remind you how the great chronicle of Pantagruel told all about Gargantua’s genealogy and the antiquity of his family. There you can find, set out at much greater length, how the giants were born into this world, and how Gargantua, Pantagruel’s father, is their descendant in a direct line. So don’t be angry if, at least for now, I don’t repeat it all, though it’s a story that couldn’t help pleasing Your Lordships even more, every time it was told. Don’t we have the authority of Plato, in his Philebus and his Gorgias, and that of Horace, too, who says there are some things—and these among them, without the slightest doubt—that become more delightful the more they’re retold?

Would to God everyone could know as much about his genealogy, from Noah’s ark down to today! I think there are lots of emperors walking the earth, these days, and kings and dukes and princes and popes, too, who are descended from peddlers of indulgences and grape baskets, just as, the other way around, there are lots of people down at the heel, suffering and miserable, who are descended by blood in a direct line from the greatest kings and emperors. Just consider the wonderful succession of kingdoms and empires:

from the Assyrians to the Medes,

from the Medes to the Persians,

from the Persians to the Macedonians,

from the Macedonians to the Romans,

from the Romans to the Greeks,

from the, Greeks to the French

And to tell you about the man who’s speaking to you, I suspect I might be descended from some rich king or prince of olden times—because you’ll never see anyone who’d rather be a king, and rich, than me, so I could spread good cheer everywhere, and never work, and never worry about anything, and pour down gold on my friends and all good and learned men. But I console myself that in the next world I’ll be grander than in this one—grander than I dare dream. Drown your own bad luck in such a thought, or a better one, and drink as much as you can, if you can.

Get the Norton Raffel translation of Gargantua and Pantagruel

Title: Gargantua and Pantagruel. Contains all 5 parts. Includes a translator's preface. Starts with Gargantua.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780393308068, 636 pages).

Who was Donald M. Frame?

Donald Murdoch Frame was an American professor of French at Columbia University. He specialized in French Renaissance literature.

» NYT Obituary of Donald M. Frame

About the Frame version of Gargantua and Pantagruel

It was published posthumously.

A sample extract from the introduction is available online at UCPress. There’s also a preview on Google Books.

Contains a list of abbreviations, a foreword, a translator’s note, an introduction, endnotes, and a glossary.

Oxford Guide to Literature in English Translation: “Renaissance Prose: Rabelais and Montaigne” by Peter France

Donald M. Frame made a fully annotated translation which is “recommended for its accuracy.”

From the translator’s note by Donald M. Frame:

“My aim in this version, as always, is fidelity (which is not always literalness): to put into standard American English what I think R would (or at least might) have written if he were using that English today.… Because R needs ample annotation, which threatens to swamp the text, to restrict the length and number of notes we offer a Selected Glossary.”

From the acknowledgments by M.A. Screech:

“Had [Donald Frame] lived he would have eliminated from his translation, as posthumously published, the gaps, errors and misreadings of his manuscript. He was a meticulous workman, a warm friend and a great scholar.”

The Washington Post: “On the Shoulders of Giants” By Michael Dirda

“The great virtue of Donald Frame’s translation lies in its fidelity to the French, extensive annotations (crucial, I think, in reading a writer as topical and allusive as Rabelais), and an exceptionally large glossary of proper names. All of these come backed by the authority of Frame, for years the leading American scholar of French Renaissance prose. Still, where Frame’s earlier translation of Montaigne seemed an uncannily exact recreation, here the Columbia professor — who died before he was fully satisfied with his work — sometimes sounds insufficiently musical and a tad low-keyed for his often florid, manic original…. Frame’s version of the Complete Works, beautifully produced by the University of California press, is certainly the one to acquire… but any version will convey some of the earthy, sourdough flavor.”

Extract from the Frame version of Gargantua and Pantagruel

I refer you to the Pantagrueline chronicle to renew your knowledge of the genealogy and antiquity from which Gargantua came to us. In this you will hear at greater length how the giants were born into this world, and how from them, in a direct line, sprang Gargantua, father of Pantagruel; and you will not be angry if for the present I forbear, although the matter is such that the more it was recalled, the more your lordships would like it; for which you have the authority of Plato, in his Philebus and Gorgias, and of Flaccus, who says that some accounts, no doubt such as these, are all the more delightful the more they are repeated,

Would God that everyone knew his own genealogy as certainly, from Noah’s Ark down to this day! I think that many today are emperors, kings, dukes, princes, and popes on earth, who are descended from relic-peddlers and firewood-haulers; just as, conversely, many are poorhouse beggars, wretched and suffering, who are descended from the blood and lineage of great kings and emperors, considering the prodigious transfer of reigns and empires: from the Assyrians to the Medes, from the Medes to the Persians, from the Persians to the Macedonians, from the Macedonians to the Romans, from the Romans to the Greeks, from the Greeks to the French.’

And, to give you knowledge of myself who am speaking, I think I am descended from some rich king or prince of the olden times; for you never saw a man who had more desire than I do to be a king and rich, so as to live luxuriously, do no work, not worry, and enrich my friends and all men of worth and learning. But in this I take comfort, that in the other world I shall in fact be greater than at present I would even dare to wish. Do you comfort your unhappiness in such a thought, or a better one, and drink cool, if that can be done.

Get the University of California Press Frame translation of The Complete Works of François Rabelais

Title: The Complete Works of Francois Rabelais. Contains a list of abbreviations, a foreword by Raymond C. La Charité, a translator’s note, and an introduction. Endnotes and glossary at the back. Starts with Gargantua.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780520064010, 1114 pages).

Who is Andrew Brown?

Andrew Brown taught French at the University of Cambridge. According to this list, he has translated French, Italian, and German writings by Stendhal, Dumas, Voltaire, Cyrano de Bergerac, Marquis de Sade, Zola, Flaubert, Proust, Machiavelli, Maupassant, Stendhal, Jules Verne, Baudelaire, and Kafka.

About the Brown translation of Gargantua and Pantagruel (Pantagruel and Gargantua)

This translation contains only the first two volumes of the work.

This translation was first published by Hesperus Press Ltd in 2003. The revised version was first published by Alma Classics in 2018. It contains an introduction by the translator, a note on the text, and notes that Brown says are “discreetly placed at the end of the book, where the reader can safely ignore them.” Interestingly, it places Pantagruel before Gargantua in the title.

Times Literary Supplement blurb:

“Andrew Brown… creates a wholly credible, modern, reinvigorated Rabelais who still jumps off the page after more than 450 years.”

Extract from the Brown version of Gargantua and Pantagruel (Pantagruel and Gargantua)

This extract is different from the others, except for Screech, because it comes from Pantagruel, not Gargantua.

IT WON’T BE A TOTAL WASTE OF TIME or space, seeing that we have I nothing else to do, if I remind you of the earliest source and origin from which the good Pantagruel came to be born among us. I see that all good history writers have set out their chronicles in this way — not only the Arabs, Barbarians and Latins, but also the Greeks, those pagan folk who never stopped drinking.

So you should note that in the beginning of the world (I’m talking of a good long while ago now, more than forty times forty nights as the ancient Druids used to reckon it), shortly after Abel was slain by his brother Cain, the earth, drenched with the just man’s blood, in one particular year brought forth in such abundance all the kinds of fruit that its fertile womb produces for us, in particular medlars, that it has gone down as the Year of the Great Medlars: there were three to a bushel.

That year, the calends were calculated according to the breviaries of the Greeks,* no part of Lent fell in March and mid-August was in May. In the month of October, I think it was, or maybe September (if I’m not mistaken: I really want to get this right), there occurred the week, so renowned in the annals, known as the Week of the Three Thursdays:* there were three of them because of the irregular leap year days, as the Sun wobbled and trespassed somewhat from its path to the left, and the Moon wandered more than thirty feet off course, and it was easy to make out the oscillation in the firmament known as Aplanes;* the tremor became so intense that the middle Pleiad, leaving its companions, declined towards the equinoctial line, and the star called Spica left its constellation Virgo and withdrew in the direction of Libra. It was all perfectly dreadful, and these phenomena were so hard and difficult to understand that astrologers just couldn’t get their teeth into them. And pretty long teeth they’d have needed to reach that far!

Get the Alma Brown translation of Pantagruel and Gargantua

Title: Pantagruel and Gargantua: Contains Books 1 and 2 only (Pantagruel and Gargantua). Includes an introduction and a note on the text. Starts with Pantagruel.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9781847497406, 256 pages).

Who was M. A. Screech?

Michael Andrew Screech was a prominent British Renaissance scholar. Burton Raffel called him “the greatest of living Rabelaisians.”

About the Screech translation of Gargantua and Pantagruel

It contains a chronology (of the life of Rabelais and the publication of Gargantua and Pantagruel), an introduction by the translator, and a note on the translation. It includes footnotes “devoted mainly to variant readings.” The texts included are:

- Pantagruel

- Pantagrueline Prognostication for 1535

- Prefaces to Almanacs for 1533 and 1535

- Gargantua

- Almanac for 1536

- The Third Book of Pantagruel

- Preface to the Fourth Book of Pantagruel (1548)

- The Fourth Book of Pantagruel (1552)

- The Fifth Book of Pantagruel

Translation and Literature: “Review of Gargantua and Pantagruel” by Barbara Bowen

Bowen heartily approves of Screech’s translation. That being said, it is impossible to adequately excerpt or summarize her articulate review. Just read the whole thing.

From the note on the translation by M.A. Screech:

“My aim here for Rabelais… is to turn him loyally into readable and enjoyable English. Here too I have not found that meaning is more loyally conveyed by clinging to French syntax and constructions. French and English often achieve similar effects by different means; they very often fall naturally into different word-orders. [However,] names are mainly kept in French. That reminds readers that these are French books anchored in French Renaissance culture.”

Extract from the Screech version of Gargantua and Pantagruel

This extract is different from the others, except for Brown, because it comes from Pantagruel, not Gargantua.

It will be neither fruitless nor idle [, seeing we are at leisure,] to recall for you the primary source and origin of our good giant Pantagruel, for I note that all fine historiographers have done likewise in their chronicles, not only those of the Greeks, Arabs and Ethnics but also the authors of Holy Writ, as Monsignor Saint Luke particularly, and Saint Matthew.4

You should note therefore that, at the beginning of this world of ours — [I am talking of long ago: more than twice-score twice-score nights to count like the ancient Druids —] it befell, one particular year soon after Abel was slain by Cain his brother, that the earth, steeped in the blood of the righteous, was so prolific in all the fruits which are produced from her loins but above all in medlars, that from time immemorial it has been called the Year of the Fat Medlars, for it took but three to make a bushel.

[In that year Kalends were found in the Greek missals; March failed to fall within Lent, and mid-August fell within May.]

It was in the month of October it seems to me or else in the month of September — so as not to fall into error: [I want scrupulously to guard against that] — that there occurred the week so celebrated in the annals which is called the Week of the Three Thursdays. There were indeed three Thursdays when the moon wandered more than ten yards from her course because of the irregular bissextile days.5

Get the Penguin Classics Screech translation of Gargantua and Pantagruel

Title: Gargantua and Pantagruel. Contains all 5 parts. Includes an introduction and footnotes by the translator. Includes a chronology and note on the translation. Starts with Pantagruel.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780140445503, 1104 pages).

Get the Penguin Classics Screech translation of Gargantua and Pantagruel

Title: Gargantua and Pantagruel. Contains all 5 parts. Includes an introduction and footnotes by the translator. Includes a chronology and note on the translation. Starts with Pantagruel.

Available as an ebook.

Gargantua and Pantagruel: Original French text

Various editions are available for each volume.

» Works of Rabelais in French at Wikisource

Get Gargantua and Pantagruel by Rabelais

Dramatised by Lavinia Murray. Starring David Troughton as Rabelais with a full cast. 2 episodes, 1 hour and 53 minutes total.

Available as audiobook (ISBN 9781471345135).

Get Gargantua and Pantagruel by Urquhart, Motteux, and Wallis

This is an old version of the Urquhart translation edited by Wallis.

Available as a FREE ebook.

Get Selections from Gargantua and Pantagruel by Edited and Translated by Floyd Gray

Out of print. Contains a 5-page introduction, a list of principal dates in the life of Rabelais, and extracts translated by Floyd Gray from the first four books (especially Gargantua), and a selected bibliography. "In making my own translation, I have been concerned first and foremost with providing an accurate, literal, readable version in modern American English.... I have made every effort to preserve some kind of narrative continuity... It is hoped that the present translation---in spite of the fact that it is only a partial one---will provide the reader with some idea of the magnificent depth and extraordinary sweep of the complete work."

Available as a paperback (ISBN 0882950681, 144 pages).

Get Rabelais and His World by Mikhail Bakhtin, translated by Helene Iswolsky

Out of print. "This classic work by the Russian philosopher and literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin (1895–1975) examines popular humor and folk culture in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. One of the essential texts of a theorist who is rapidly becoming a major reference in contemporary thought, Rabelais and His World is essential reading for anyone interested in problems of language and text and in cultural interpretation."

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780253203410, 512 pages).

Get Rabelais by John Cowper Powys

Out of print. "Rabelais: His life and the story he told, selections therefrom here newly translated, and an interpretation of his genius and his religion." About 150 pages are translated excerpts. Published in 1948.

Available as a hardcover.

Get A Companion to François Rabelais by Bernd Renner, editor

"Two sections of this volume situate Rabelais’s work in the larger social, political, and literary context of his time. A third section gives concise interpretations of each of the five books of the Pantagrueline Chronicles.The contributors are eminent scholars of early modern literature."

Available as a hardcover (ebook also available) (ISBN 9789004360037, 623 pages).

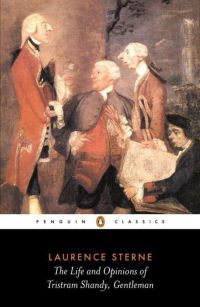

Get The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman by Laurence Sterne

A novel heavily influenced by Gargantua and Pantagruel. "Laurence Sterne's great masterpiece of bawdy humour and rich satire defies any attempt to categorize it, with a rich metafictional narrative that might classify it as the first 'postmodern' novel. Part novel, part digression, its gloriously disordered narrative interweaves the birth and life of the unfortunate 'hero' Tristram Shandy, the eccentric philosophy of his father Walter, the amours and military obsessions of Uncle Toby, and a host of other characters, including Dr Slop, Corporal Trim and the parson Yorick."

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780141439778, 735 pages).

Oh, it’s tough to pick one! As usual, you’ll need to choose according to your purpose and your personal taste.

Five older translations:

From the translator’s introduction by Floyd Gray to Selections from Gargantua and Pantagruel:

“Sir Thomas Urquhart and Peter Motteux, Rabelais’s seventeenth-century translators, were eminently successful in capturing the tone and texture of the original; but their version is a veritable re-creation, a brilliant recasting and expansion rather than a faithful translation. More recent translators [Putnam, Leclerc, and Cohen—all out of print now]… adhere more closely to the text, but Leclerc interlards it with parenthetical explanations and Putnam and Cohen are frequently archaic in language as well as in syntax.”

Urquhart sounds like a fascinating person, and his translation, considered a classic in its own right, is available today in hardcover, paperback, and free ebook versions. Definitely worth considering.

The 1893 Smith translation, which omitted or toned down bawdy content, according to Wikipedia was criticized for “trying to match Rabelais’ sentence forms exactly, which renders the English obscure in places.” There’s nothing particularly to recommend this version now that there are several others to choose from, and anyway, it’s out of print.

Three complete in-print modern translations:

To choose between these (Norton/Raffel, UCP/Frame, Penguin/Screech), preview the text and see what it sounds like, see which you prefer. Also ask yourself how much extra academic apparatus you’re interested in (Raffel – none, Screech – a lot, Frame – the most).

Raffel says in his intro: “I have tried to devise a flexible and responsive contemporary English prose equivalent, while trying at the same time to capture as much as I possibly could of the sweep and slash of Rabelais’ writing.” This is the version to choose if you just want a lively story and don’t want to be bothered with footnotes, endnotes, or even an introduction.

Frame says in his intro: “My aim in this version, as always, is fidelity (which is not always literalness): to put into standard American English what I think R would (or at least might) have written if he were using that English today.” This is the version to choose for serious scholarship. There are some brackets in the text, but the notes are endnotes, so they don’t get in the way.

Screech says in his intro: “My aim here for Rabelais… is to turn him loyally into readable and enjoyable English.” This is the Penguin Classics edition. Make sure you’re okay not just with lots of footnotes but also with all the square brackets in the text (see extract above).