“Which English translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame should I read?”

So, you want to read Victor Hugo’s wildly popular novel. Originally published in 1831, it’s been translated more than a dozen times and adapted for comics, children’s books, plays, tv shows, and movies—including, of course, a Disney animated feature film.

You might think it’s a dramatic story about a deformed bell-ringer, a priest, a captain, and a dancing girl with a goat, but it was actually written with the primary objective of arousing public interest in preserving threatened Gothic architecture in France.

Hugo succeeded. Maybe video killed the radio star, but the printing press still hasn’t killed architecture. The internet—modern-day heir to the printing press—in April 2019 helped raise millions of dollars, literally overnight, to salvage the cathedral Hugo loved.

TLDR?

I found so much information on translations of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame that I had to split this post into two. If you just want a quick-and-dirty recommendation on which translation to choose, jump to the conclusion of Part 2.

The Hunchback of Notre-Dame: Translations in English

Many of the old translations are still out there today! Translators not getting their names on stuff was common practice in the 1800s; reprinting old public domain translations is common practice now; and if I’m not mistaken, some translators whose names were on their translations aren’t getting credit for today’s reprints. Wherever I’ve had to try, by looking at extracts, to identify the translation in a newer edition, I’ve added a note to say so.

Described Below (on this page)

- 1833 – William Hazlitt

- 1833 – Frederic Shoberl

- 1839 – Anonymous (Foster and Hextall)

- 1862 – Henry L. Williams

- 1882 – A. Langdon Alger

- 1888 – Isabel F. Hapgood

- 1888 – Anonymous (Little, Brown, & Co.)

- 1892 – J. Carroll Beckwith

Described in Part 2 (separate page)

- 1902 – Jessie Haynes

- 1941 – Anonymous (Modern Library)

- 1956 – Lowell Bair (ABRIDGED, Bantam)

- 1964 – Walter J. Cobb (Signet)

- 1978 – John Sturrock (Penguin)

- 1993 – Alban J. Krailsheimer (Oxford)

- 2002 – Anonymous (Modern Library) edited by Catherine Liu (Modern Library)

The Hunchback of Notre-Dame: Translation Comparison

Extracts have been included below so that you can see how the different translations sound.

Why was the title changed from Notre-Dame de Paris to The Hunchback of Notre-Dame?

The original French title, Notre-Dame de Paris, means “Our Lady of Paris” and refers to the cathedral of the same name.

The foreword to the Tor edition says, “First translated into English in 1833 by William Hazlitt the Younger as Notre Dame of Paris, the novel was released only a few months later in a second translation [by Shoberl] as The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and has been known to English speakers by this title ever since.”

Articulating Bodies by Kylee-Anne Hlingston

“Shoberl’s [1833] translation gave the story its standard English name—The Hunchback of Notre-Dame—recentering the multi-plot novel on the deformity of a single character rather than on the cathedral’s looming presence. Kenneth Ward Hooker argues that this change in title reflects publisher Richard Bentley’s ‘knowledge of English taste’ as well as his wisdom in broadening the novel’s audience: ‘For the antiquaries [attracted to Hazlitt’s subtitle, A Tale of the ‘Ancien Regime’] were outnumbered perhaps a hundred to one by the readers who were just looking for a good story.'”

Were chapters of Notre-Dame de Paris lost?

Three chapters were added in 1832 that were not included in the original Hazlitt, Shoberl, or Foster and Hextall translations:

- Impopularité (Unpopularity)

- Abbas Beati Martini

- Ceci Tuera Cela (This Will Kill That)

In an 1832 note by the author (included in this 1899 edition), Hugo explains that “new” chapters had been added which were in fact not new but lost and recovered.

[T]hese added chapters were not written expressly for this reprint. If they have never been published in former editions of the book, it is for a very simple reason. When ” Notre-Dame ” was printed for the first time, the bundle of papers among which were these chapters was missing. It was necessary to rewrite or to omit them. The author reflected that the only chapters that might have been important in their scope were the two on art and history, whose loss would in no way affect the drama or the romance itself; that the public would be none the wiser concerning this disappearance, while only the author himself would be aware of the secret gap. He concluded to continue without them. And besides, if all must be told, his indolence recoiled from the task of rewriting the lost chapters. He would have found it less work to write a new romance.

But now the chapters are recovered, and he seizes the first opportunity to insert them where they belong.

Here, then, is his work in its entirety, — the thing he dreamed, the thing he has accomplished; good or bad, lasting or frail, it is as he wished it.

Scholars say it’s true the chapters are original and that including them was “as he wished it”. What isn’t true is that the chapters were omitted from early editions by mistake.

French Forum: “Inscribing his Ideal Reader(ship)” by Isabel K. Roche

“While it is well known that these chapters were never in fact lost, but rather were held back by Hugo so as to ensure the commercial success of his novel, what is most interesting here is that Hugo deliberately draws attention in this notice to two possible readings (and readers) of Notre-Dame de Paris: one typical and ordinary and the other informed and enlightened.”

And still today, the book can be enjoyed simply as a drama—or as a philosophical argument about architecture.

Who was William Hazlitt the Younger?

Son of the critic William Hazlitt, William Hazlitt the Younger was an English lawyer, writer, and translator. His son and his grandfather were also named William Hazlitt.

About the Hazlitt translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

The title of this translation was originally Notre-Dame: A Tale of the Ancien Regime.

The Oxford Guide to Literature in English Translation edited by Peter France on page 278 says that Hazlitt’s translation was “unfortunately based on the first edition” and uses “antiquated English.”

Articulating Bodies by Kylee-Anne Hlingston

Hazlitt’s translation was “less popular” than Shoberl’s, which was cheaper, illustrated, and “aimed at a wider audience than Hazlitt’s expensive and essentially unillustrated one.” (pages 22–23).

From Hazlitt’s “Prefatory Notice”:

“We have called this a tale of the ‘ancient regime.’ We use this term in the most comprehensive sense, as expressing the violent internal state of things in France…. The new regime… however short of perfection in its details… is in its principle a regime of right” (xx-xi).

“In rendering from one language into another a work of fiction consisting almost wholly of dialogue and incident, in which there is little or no occasion to make the author appear in propria persona, it is clear that the mode most convenient for embodying those scattered words and sentences of illustration, which, in such a case, are always found necessary, is that the translator should speak in his own person. This course the editor of these volumes has adopted, finding it convenient to himself, conceiving it to be advantageous to the reader, and confident that it implies no disrespect for the author, seeing that such passages as the translator is wholly responsible for, will, by their own internal evidence, betray themselves to the reader” (xxviii).

The current hardcover Everyman’s Library edition says: “This edition reprints the anonymous nineteenth-century translation used by the first Everyman edition in 1910.” However, the text seems to match the Hazlitt translation, and Peter France acknowledges that it’s a reprint in The Oxford Guide to Literature in English Translation. The original Hazlitt translation, however, does not have the three “missing” chapters, and the Everyman edition does. So Hazlitt later translated the added chapters, or someone built on his translation subsequently (by copying most of it word for word).

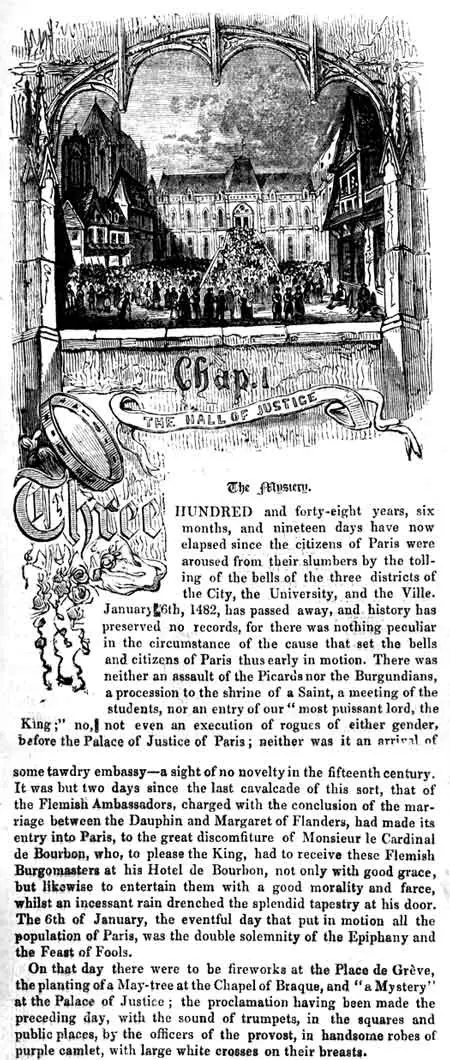

What’s interesting about the Hazlitt translation is how the beginning of the first chapter got so much longer than the first chapter in the original French. There is quite a lot of material that appears to have been inserted regarding the Feast of Fools. See extracts below.

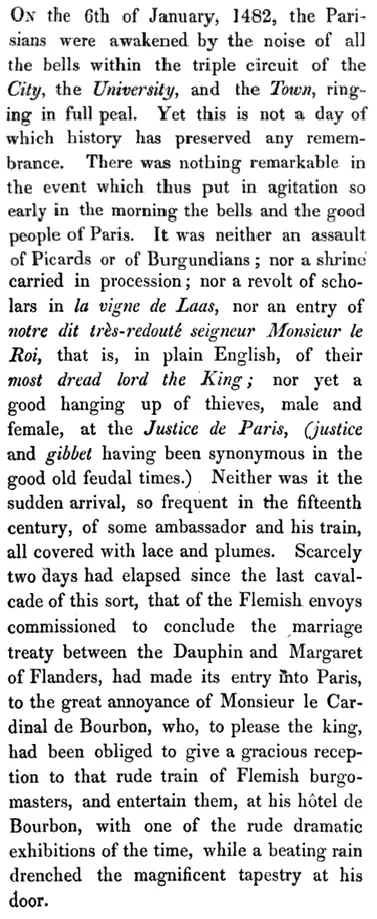

Extract from the Hazlitt translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

From the original Hazlitt translation:

Read the corresponding extract from the “anonymous” Everyman edition.

Get the Hazlitt translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

This translation is in the public domain. There are digital scans of the three volumes available free at Google Books:

Notre-Dame: A Tale of the Ancien Regime (Vol I)

Get the Everyman's Library Hazlitt translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

Includes an introduction by Jean-Marc Hovasse. "This edition reprints the anonymous nineteenth-century translation used by the first Everyman edition in 1910." I checked several scattered passages; looks like Hazlitt to me.

Available as a hardcover (ISBN 9780307957818, 504 pages).

Who was Frederic Shoberl?

Frederic Shoberl was an English writer, translator, and illustrator.

About the Shoberl translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

Articulating Bodies by Kylee-Anne Hlingston

“Shoberl’s translation slightly bowdlerized Hugo’s original, cutting a few blasphemies… and overtly sexual references ‘which, though not startling to our continental neighbours, would offend the severer taste of the English reader’ (Shoberl xiii-xiv).” Hazlitt’s was “less popular”; Shoberl’s was cheaper, illustrated, and “aimed at a wider audience than Hazlitt’s expensive and essentially unillustrated one…. The [Shoberl] edition’s affordability, popular retitling, and minor censorship to accommodate English prudery, as well as its positive reviews and reprintings, lead me to believe that Shoberl’s translation was the most influential edition in popularizing Hugo’s novel in England” (pages 22–23).

In Encyclopedia of Literary Translation into English edited by Olive Classe, (Volume 1, page 673), John R. Whittaker says, “[Shoberl’s] translation is sound and clear, and there is no doubt that his example influenced subsequent versions. Shoberl attempts, from time to time, to allude to the medieval setting by inserting archaisms.”

From Shoberl’s “Sketch of the Life and Writings of Victor Hugo”, which prefaces his translation:

“[I]t would be useless to accumulate opinions upon a work now before the British public, which can of course form its own judgment upon it. The translator will therefore merely add, that this version has been made with care; that it has been his aim in the task to preserve as much as possible the peculiarities of the author’s style and manner; and that he has taken no further liberty with the original than here and there pruning away certain luxuriances, or softening down expressions, which, though not startling to our continental neighbours, would offend the severer taste of the English reader” (page xi).

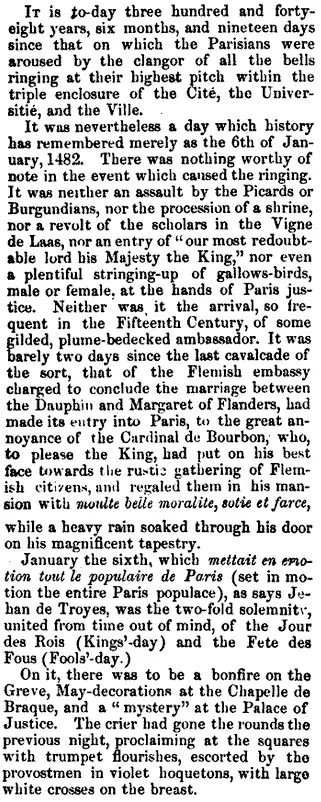

Extract from the Shoberl translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

Get the Shoberl translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

This translation is in the public domain. Scans are freely available online at Archive.org, Google Books, and Hathi Trust:

Get the Tor Shoberl translation of The Hunchback of Notre Dame

"This edition of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame includes a Foreword, Biographical Note, and Afterword by Elizabeth Massie." Complete and unabridged. There's no translator credited but the text seems to match the Shoberl translation. This book is out of print, but you may be able to find a second-hand copy using the links below.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780812563122, 480 pages).

Get the Tor Shoberl translation of The Hunchback of Notre Dame

"This edition of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame includes a Foreword, Biographical Note, and Afterword by Elizabeth Massie." Complete and unabridged. There's no translator credited but the text seems to match the Shoberl translation. If Amazon doesn't have the ebook, try Macmillan.

Available as an ebook (ISBN 9781466804814).

About the Anonymous Foster and Hextall translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

Articulating Bodies by Kylee-Anne Hlingston

“This unsigned translation was published in six parts in Foster and Hextall’s The Novelist: A Collection of the Standard Novels.”

Volume 1 of The Novelist is 494 pages and contains: The last of the Mohicans; Lionel Lincoln; Clarence; The pilot; and La Esmeralda, or, The hunchback of Notre Dame (pages 401 to 494). On the page where La Esmeralda begins, it says “Translated expressly for ‘The Novelist,’ from the original French.” The text is miserably tiny, and in two columns, but I don’t think it’s abridged.

I gather that the book is a reprint of what was basically a bunch of issues of a cheap magazine, where people would buy each issue for a small price. After all the issues had been published, then the same publishers (Foster and Hextall) and at least one other (Peirce) put out a version of the same text that readers could buy as a whole volume rather than as separate issues.

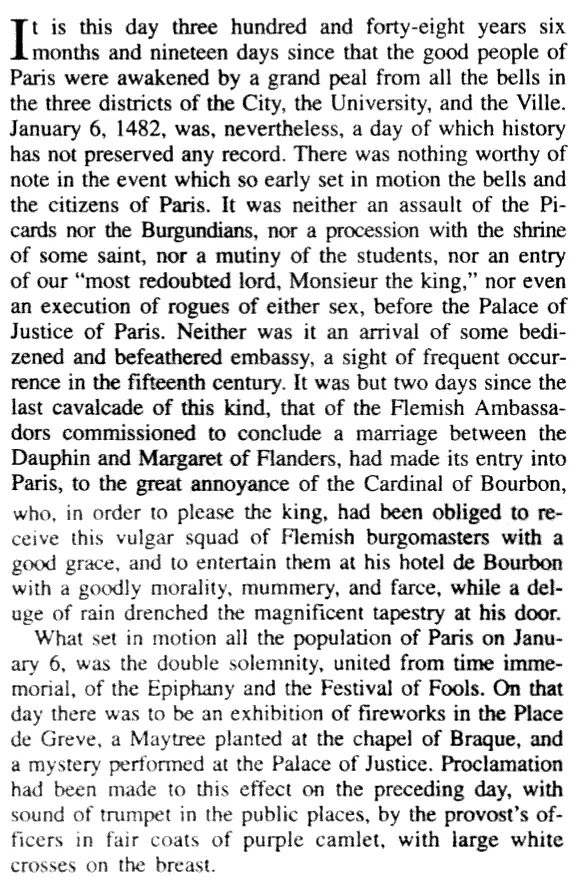

Extract from the Anonymous Foster and Hextall translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

Extract from the Peirce reprint:

Get the Anonymous Foster and Hextall translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

The Novelist Vol 1, 1839

London/G. Peirce reprint, 1844

“This work will contain three chapters never before published in England, having but just appeared in the eighth edition, now in course of publication in Paris.”

Who was Henry L. Williams?

Henry Llewellyn Williams, Jr. was an American writer and translator.

John Adcock: “Henry Llewellyn Williams (Sr.): A Literary Pirate”

According to an 1883 article quoted in a blog post by John Adcock, the work that H.L. Williams did with his father, also a writer, may not have been completely legitimate.

The Alexandre Dumas père Web Site: “Henry Llewellyn Williams Jr.” by CadyTech

“Translated many works of Alexandre Dumas into English for lesser-known American publishers, often with unusual or variant titles.”

Among his translations of works by Dumas is The Three Musketeers.

About the Williams translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

In Encyclopedia of Literary Translation into English edited by Olive Classe, (Volume 1, page 673), John R. Whittaker says, “Williams’s The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (1862) reads quite well, though in an attempt to make the language as accessible as possible, the lexical range of the original may have been diminished.”

Extract from the Williams translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

Get the Williams translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

This translation is in the public domain. Scans are freely available online at Hathi Trust and Google Books.

Who was A. Langdon Alger?

Abby Langdon Alger was an American writer, ethnologist, and translator.

About the Alger translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

The title of this translation was originally Notre-Dame de Paris.

In Encyclopedia of Literary Translation into English edited by Olive Classe, (Volume 1, page 673), John R. Whittaker says, “Alger’s Notre-Dame de Paris (1891) contains a number of variations from the original sense, though they are generally justified in a clear rendering which keeps the spirit of the source.”

Extract from the Alger translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

Get the Alger translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

This translation is in the public domain. Scans are freely available online at Archive.org.

Get the Dover Alger translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

"This Dover edition, first published in 2006, is an unabridged one-volume republication of Notre Dame de Paris, published in two volumes by H.M. Caldwell Co., New York and Boston, 1888." Copyright notice says translated by A.L. Alger.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780486452425, 448 pages).

Get the Dover Alger translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

"This Dover edition, first published in 2006, is an unabridged one-volume republication of Notre Dame de Paris, published in two volumes by H.M. Caldwell Co., New York and Boston, 1888." Copyright notice says translated by A.L. Alger.

Available as an ebook (ISBN 9780486114507).

Get the Barnes & Noble Alger translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

Contains quotes from the novel, an author bio, extra material on the author and novel, the author's note added to the definitive edition, an introduction by Isabel Roche, endnotes, a list of works inspired by the novel, comments and questions, and suggestions for further reading. It says "Translated anonymously" but the text seems to match the Alger translation.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9781593081409, 544 pages).

Get the Barnes & Noble Alger translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

Contains quotes from the novel, an author bio, extra material on the author and novel, the author's note added to the definitive edition, an introduction by Isabel Roche, endnotes, a list of works inspired by the novel, comments and questions, and suggestions for further reading. It says "Translated anonymously" but the text seems to match the Alger translation.

Available as an ebook (ISBN 9781411432352).

Who was Isabel F. Hapgood?

She was an American writer and translator. She was strongly religious, and worked on uniting different Christian denominations. She translated works by Tolstoy, Chekhov, and Dostoevsky, among others. She translated not only Notre-Dame de Paris by Victor Hugo, but also Les Miserables and Toilers of the Sea.

About the Hapgood translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

The title of this translation was originally Notre-Dame de Paris.

The Oxford Guide to Literature in English Translation edited by Peter France on page 278 says “All of [these 19th-c. translations], especially Hapgood’s sometimes inaccurate rendering, show their age; none has the intense vitality which characterizes Hugo’s prose at best.”

Extract from the Hapgood translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

Get the Hapgood translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

This translation is in the public domain. Digital ebooks are freely available online (see below).

Get the Thomas Nelson Hapgood translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

A fine exclusive edition of one of literature’s most beloved stories. Featuring a laser-cut jacket on a textured book with foil stamping, all titles in this series will be first editions. No more than 10,000 copies will be printed, and each will be individually numbered from 1 to 10,000. Hapgood is credited on the title page.

Available as a hardcover (ISBN 9780785239772, 640 pages).

Get the Word Cloud Classics Hapgood translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

Hapgood is credited on the title page. Word Cloud Classics have a flexible plastic/vinyl cover. They're not exactly hardcovers, but they're a step up from paperbacks in terms of esthetics and durability.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9781645171782, 624 pages).

Get the AmazonClassics Hapgood translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

Hapgood is credited on the title page. Possibly free. Definitely free if you subscribe to Kindle Unlimited.

Available as an ebook.

Get the Project Gutenberg Hapgood translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

Free! Available in html, epub, Kindle, and plain text formats.

Available as an ebook.

Get the Standard Ebooks Hapgood translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

Free! Available in epub, Kindle, Kobo, and Advanced epub formats. Standard Ebooks are professionally edited, professionally designed versions of the Project Gutenberg texts.

Available as an ebook.

About the Anonymous (Little, Brown, & Co.) translation of The Hunchback of Notre Dame

I dug this translation up from the shadowy depths of the internet myself. It doesn’t exactly match any of the other translations. It could be a new translation, or possibly an updated edition of the 1882 Alger translation, its most recent predecessor; to me the wording looks similar. In any case, there are many differences from other editions, as the publishers state in the preface:

The present edition of Notre-Dame will be found more complete than any which has hitherto been printed in English. It contains a special translation of Book V., embracing the chapter entitled “Abbas Beati Martini,” and the important chapter on Architecture and Printing; also the author’s long note added to the edition of 1832, and not included in any other translation. The English edition has been carefully examined and a number of errors have been corrected.

Boston, June 6, 1888

Extract from the Anonymous (Little, Brown, & Co.) translation of The Hunchback of Notre Dame

Get the Anonymous (Little, Brown, & Co.) translation of The Hunchback of Notre Dame

This translation is in the public domain. Scans are freely available from Hathi Trust, Archive.org, and Google Books. There are multiple copies; here are some representative links.

Who was J. Carroll Beckwith?

Strangely, as far as Wikipedia is concerned, James Carroll Beckwith was a portrait and landscape painter, not a translator, yet someone named J. Carroll Beckwith is definitely responsible for a translation of Notre-Dame of Paris. It’s possible there are two people with similar names who have become conflated, but Worldcat attributes the Beckwith translation and the Beckwith art to the same person, a man who was born in 1852 and died in 1917. Perhaps he didn’t translate anything else, and his paintings were just more memorable than his writing.

This book tells the real-live story of a police detective who believes he was the painter Carroll Beckwith in a past life.

About the Beckwith translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

The title of this translation was originally Notre-Dame of Paris.

The Oxford Guide to Literature in English Translation edited by Peter France says Beckwith’s translation “reads quite fluently, adding brief glosses as it goes, treating Hugo’s syntax rather freely and sometimes failing to catch the meaning of the dialogue” (page 278).

In Encyclopedia of Literary Translation into English edited by Olive Classe, (Volume 1, page 673), John R. Whittaker says, “Beckwith’s The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (1899, 1953) combines respect for the original with a competence that has justified a number of reprints in more recent times.”

Beckwith’s note on the translation in the 1892 edition says:

“If translated too literally, the English becomes harsh, disconnected; if rendered into modern, well-rounded phrases, the virility the peculiar historical accent, disappear…. [I]t behooves the translator to consider his quantities even more carefully, if possible, than did the author himself,—working as he does in an alien tongue as well as an alien time.”

Extract from the Beckwith translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

Get the Beckwith translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

This translation is in the public domain. Scans are freely available online at Archive.org.

Get the Wordsworth Beckwith translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

With an Introduction and Notes by Keith Wren. Beckwith is credited on the Wordsworth Classics UK website.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9781853260681, 480 pages).

Get the Collector's Library Beckwith translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

Includes an afterword by John Grant. I couldn't find any translator credit, but the text seems to match the Beckwith translation.

Available as a hardcover (ISBN 9781909621619, 664 pages).

Get the Collector's Library Beckwith translation of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

Includes an afterword by John Grant. I couldn't find any translator credit, but the text seems to match the Beckwith translation.

Available as an ebook (ISBN 9781509826841).

What’s in Part 2?

- translations by Haynes, Modern Library (1941 edition and 2002 edition revised by Catherine Liu), Bair, Cobb, Sturrock, and Krailsheimer.

- other information and resources (study guides, the original French text, and biographies of Hugo and the cathedral itself).

If you just want a quick-and-dirty recommendation on which translation to choose, jump to the conclusion of Part 2.