“Which English translation of In Search of Lost Time should I read?”

No matter which English translation of Proust’s massive work you choose, reading the whole thing will be a challenge, simply in terms of length. It was published in French from 1913 to 1927 in seven volumes totaling over four thousand pages.

You could just read the first volume only, if you want, and then see whether you feel like reading the rest of it.

» What’s the best translation of Swann’s Way?

Clocking in at over 1.2 million words, A la recherche du temps perdu, originally translated into English as Remembrance of Things Past, holds the Guinness Book World Record for longest novel. Other long novels include The Dream of the Red Chamber, which is estimated to be almost 1 million words, The Tale of Genji, which is about 750,000 words; War and Peace and Journey to the West, both about 600,000 words; and the notoriously long and often abridged Les Misérables, at “only” 500,000 words.

New York Times: “Marcel Proust at 100” by William H. Gass

“When reading, one wonders first if the book will ever end, and then, in despair, if it will ever begin. In comparison, the Russian steppes, were they so vast? Or winters in upper Michigan prolonged?”

From the introduction by Adam Watt to the Nelson translation:

“A la recherche du temps perdu is a massive novel that invites its readers to take a big gamble: read me, it says, page after page, volume after volume, and see what return you might get on your investment. Will it be time well spent or time wasted?”

Why is In Search of Lost Time so long?

Bookforum: “Ruminations in an Emergency: A New Translation of Proust’s Late Masterpiece” by Rebecca Ariel Porte

“[It’s] a fictional reconstruction of a life and a world that moves from the idyll of Belle Époque France to the aftermath of World War I, touching on the Dreyfus affair, anti-Semitism, and French nationalism; winding through the salons and bedrooms of Parisian high society; and exploring arcane permutations of anxiety, jealousy, aggression, attachment, solipsism, possessiveness, loneliness, boredom, coercion, luxury, art, love, class, time, memory, madeleines with lime-blossom tisanes, and queer desire.”

So should I read In Search of Lost Time?

Lithub: “Really, Here’s Why You Should Read Proust” by William C. Carter

“I always tell anyone who might be intimidated by the many pages to be read that, although In Search of Lost Time is rich and complex and demands an attentive reader, the novel is never difficult…. Over the years, I have received unsolicited testimony from many such readers who say that Proust changed their lives by giving them a new and richer way of looking at the world…. In the closing pages, Proust urges each of us to comprehend, develop, and deploy our remarkable faculties. He intends his entire enterprise to persuade us that we are incredibly rich instruments, but that most often we let our gifts lie dormant or we squander them. The joy that so many readers feel at the conclusion of the book derives from the long-delayed triumph of the hero and the realization that we too can, by following his example, attempt to lead the true life. When the Narrator completes his quest, after many ups and downs and misunderstandings, the myriad themes—major and minor—beautifully orchestrated throughout, are gloriously resolved in the grand finale. This happy ending makes In Search of Lost Time a comedy of the highest order, one that amuses, delights, and frequently dazzles, as it instructs…. I urge anyone who loves books and who has not yet discovered Proust’s novel to pick up Swann’s Way and dive right in. I assure you that you will be richly rewarded.”

TL;DR: In Search of Lost Time: “Best” Translation in English

I found so much information on translations of In Search of Lost Time that I had to split this post into two. If you just want a quick-and-dirty recommendation on which translation to choose, jump to the Conclusion of Post 2.

In Search of Lost Time: Translations in English

There are only two complete translations: the original one by Scott Moncrieff, and a much more recent one by multiple translators organized by Penguin. But wait, there’s more…

Described Below (on this page)

These versions are still in print, except for Blossom’s Vol 7.

- 1922–1932 – C.K. Scott Moncrieff and Stephen Hudson or Frederick Blossom

- 1931 – Vol 7 = Time Regained, translated by Sydney Schiff writing as Stephen Hudson (UK)

- 1932 – Vol 7 = The Past Recaptured, translated by Frederick Blossom (US)

- 1981 – Scott Moncrieff and Andreas Mayor revised by Terence Kilmartin

- 1970 – Vol 7 = The Past Recaptured / Time Regained, translated by Andreas Mayor

- 1992 – Scott Moncrieff and Andreas Mayor revised by D.J. Enright

Described in Post 2 (separate page)

- 1995–2002 – multiple translators under Christopher Prendergast

- 2013–2025 – Scott Moncrieff revised by William C. Carter

- 2023–20?? – multiple translators under Brian Nelson and Adam Watt (ongoing)

In Search of Lost Time: Translation Comparison

Extracts have been included so you can see how the different translations sound.

Why does the novel have two titles?

Scott Moncrieff chose the title “Remembrance of Things Past.” The English title adopted in 1992, which is now generally considered more accurate and thus more appropriate, is “In Search of Lost Time.”

Bookforum: “Review of Swann Songs: A new biography of translator C. K. Scott Moncrieff” by Eric Banks

“That phrase from Shakespeare’s ‘Sonnet 30,’ while lovely, ‘cannot possibly mean what you say,’ Proust wrote, registering a complaint that would dog Scott Moncrieff’s translation in both letter and spirit for times to come.”

The titles he chose for the individual volumes are also controversial. In particular, the title of Volume 1 was supposed to match up with the title of Volume 7. Instead, Scott Moncrieff chose titles that would be familiar to English readers from poems.

Grand Street: “Translating Proust” by Terence Kilmartin

“Scott Moncrieff’s strengths and weaknesses are neatly epitomized in the titles he chose for the novel as a whole and for the individual sections. They are stylish and ingenious, and at the same time slightly out of key.“

Proustonomics: “C.K. Scott Moncrieff, poet, spy & Proust’s translator: interview with Jean Findlay” by Nicolas Ragonneau

“Each title had to entice an English speaking audience as its first priority, and that audience would be a literary one, so a line from Shakespeare’s sonnet no 30 would be known as such ‘When to the sessions of sweet silent thought, I summon up remembrance of things past’. Charles’s translation was a work of art in itself, bearing in mind the audience of his day and how to sell to that audience. He was also a successful critic and literary figure and knew as Noel Coward advised ‘never bore your audience to death’. A faithful and clunking translation would alienate the readership.”

Public Domain Review: “Lost in Translation: Proust and Scott Moncrieff” by William C. Carter

On the meaning of Proust’s title: “Proust’s theory of memory rejects the notion that we can simply sit and quietly resurrect the past in its true vividness through what he called voluntary memory. When we attempt to do this, we find that it doesn’t work very well. We remember very little and often only in a haphazard and rather bland way. On the other hand, Proust’s title should be taken to suggest [that] the Narrator’s search… is an active, arduous quest in which the past must be rediscovered—largely through what Proust called involuntary memory, as demonstrated in the famous madeleine scene—then analyzed and understood, and finally, if your ambition is to preserve it in writing, transposed and recreated in a book.”

From the General Editor’s Preface by Christopher Prendergast to the Penguin translation:

“There will always be fans of Scott Moncrieff’s prettily Shakespearean Remembrance of Things Past. But we also know that Proust took vigorous exception to Scott Moncrieff’s title, and for good reason. It removes virtually everything expressed or implied by the original.”

How many volumes does In Search of Lost Time have?

Well, that depends. Probably three, four, six, or seven volumes.

It’s hypothetically only one volume if you only read the first volume, usually titled Swann’s Way. There’s a separate page comparing translations of Swann’s Way.

The complete novel is three volumes if you get the Scott Moncrieff and Kilmartin version from Vintage or the Scott Moncrieff version from Penguin Classics.

The complete novel is four volumes if you get the Scott Moncrieff and Enright hardcover boxed set from Everyman’s Library.

The complete novel is six volumes if you get the Scott Moncrieff and Enright set from Vintage Classics or Modern Library, or if you get the Penguin Modern Classics set, or the Yale set.

The complete novel is seven volumes if you get the Penguin Classics Deluxe set.

Originally, the novel was printed in even more volumes, like twelve.

What are the titles of the volumes of In Search of Lost Time?

| French | English |

| 1. Du côté de chez Swann | 1. Swann’s Way -or- The Way by Swann’s -or- The Swann Way |

| 2. À l’ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs | 2. Within a Budding Grove -or- In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower -or- In the Shadow of Girls in Blossom |

| 3. Le Côté de Guermantes | 3. The Guermantes Way |

| 4. Sodome et Gomorrhe | 4. Cities of the Plain -or- Sodom and Gomorrah |

| 5. La Prisonnière | 5. The Captive -or- The Prisoner |

| 6. Albertine disparue | 6. The Sweet Cheat Gone -or- The Fugitive |

| 7. Le Temps retrouvé | 7. Time Regained -or- The Past Recaptured -or- Finding Time Again |

Is there an English version of In Search of Lost Time in the public domain? (Can I get it for free?)

The complete original French text is in the public domain as of January 1, 2023. New translations can be published without any need to ask for permission or pay a fee for translation rights.

» Download original French text from Wikisource

Each English translation has its own copyright.

The volumes of Scott Moncrieff’s English translation were published in 1922, 1924, 1925, 1927, 1929, 1930, and 1931. The four volumes published before 1928 are definitely in the public domain. As of end-2023, the other three volumes are not in the public domain in the US. The other versions are also too recent to be in the public domain.

Are the writers who work on this novel “cursed”?

No. But many of them, including Proust himself, have left their work unfinished.

- When he died, Proust had not finished editing the last three volumes.

- Scott Moncrieff was unable to complete his translation of volume 7.

- Andreas Mayor (translator of volume 7) was to translate the other volumes as well.

- Terence Kilmartin developed a brain tumor (which he survived).

- Richard Howard began and abandoned a complete translation (he only shared a few pages).

- James Grieve only produced translations of volumes 1 and 2 before he died.

Letters Republic: “In Search of Penguin’s Proust” by Kevin Donovan

Proust and popular fantasy novelist Robert Jordan (and, someday, with increasing likelihood, George Martin) suffered from the so-called magnum opus death curse. “Like ascending the slopes of Everest, tackling Proust meant passing a number of the failed and dead along the way…. The book, it seemed, was too much for any one person to labor on alone and survive.”

World Press Review: “My Madeleine Is Rich” by Christophe Boltanski

“It seems to me [Prendergast] that the heroic era of literary translation by a single person is over…. So we felt we had to undertake it as a team.”

Where can I get more background info on Proust and In Search of Lost Time?

Jump to the Other Books section of Post 2 for a list of biographies and guides.

Who was C.K. Scott Moncrieff?

Charles Kenneth Scott Moncrieff, surname “Scott Moncrieff”, was a Scottish writer, translator, and poet. He knew Scots, English, French, Italian, German, Latin, and ancient Greek (!!!). He died at age 40 without having finished his translation of Proust’s novel.

Jean Findlay, his great-great-niece, published a biography of him titled Chasing Lost Time: The Life of C. K. Scott Moncrieff: Soldier, Spy, and Translator and a volume of his writings titled ANT: Collected Short Stories, War Serials, and Selected Poems of C.K. Scott Moncrieff.

Who was Stephen Hudson (Sydney Schiff)?

Sydney Schiff was a British novelist and translator who wrote under the pseudonym ‘Stephen Hudson.’ He was friends with Proust.

Wikipedia: “Stephen Hudson”

“Schiff’s novels are now almost entirely forgotten; but his and his wife’s significance as key figures of early Modernism, both as friends and facilitators to several major artists and writers, has recently been reassessed by Stephen Klaidman in a joint biography of the couple, Sydney and Violet: Their Life with T.S. Eliot, Proust, Joyce and the Excruciatingly Irascible Wyndham Lewis (2013).”

Who was Frederick Blossom?

Frederick A. Blossom was the American professor, editor, author, translator, and activist who was commissioned by Random House to translate volume 7. His translation is out of print.

» More about Frederick Blossom from the University of Wisconsin Digital Archive

» NYT Obituary of Frederick Blossom

About the Scott Moncrieff translation of In Search of Lost Time (Remembrance of Things Past)

Scott Moncrieff started his translation before Proust had finished writing all seven volumes.

Volume titles:

- Swann’s Way

- Within a Budding Grove

- The Guermantes Way

- Cities of the Plain

- The Captive

- The Sweet Cheat Gone

- Time Regained

Bookforum: “Review of Swann Songs: A new biography of translator C. K. Scott Moncrieff” by Eric Banks

“[Moncrieff] carried on with his own private translation without any commitment from a publishing house to back it up…. [Faults in his translation include] his sometimes purple prose (which Lydia Davis has called “dressy”), his reliance on faulty source materials, and the downright muddled passages in which he, perhaps out of sheer fatigue with the project, lost track of the narrative…. But as Jean Findlay reminds us in her new biography Chasing Lost Time, the fact that the second (and only other) English translation of Proust relied on seven translators (including Davis)—it being considered ‘beyond the capability of one single person to translate Proust’—only underscores how superhuman was the devotion and drive of Scott Moncrieff.”

Public Domain Review: “Lost in Translation: Proust and Scott Moncrieff” by William C. Carter

“Scott Moncrieff died in 1930, at age forty, leaving untranslated the final volume Le Temps Retrouvé. His task would be completed by Sydney Schiff, writing as Stephen Hudson. Schiff dedicated his translation: ‘To the memory of my friend CHARLES SCOTT MONCRIEFF, Marcel Proust’s incomparable translator.’”

FSG Work in Progress: “Soldier, Spy, Translator: The Life of C.K. Scott Moncrieff” by Jean Findlay

“So inspired was his translation that some critics felt he was improving on the original. Joseph Conrad wrote to him in 1922: ‘I was much more interested and fascinated by your rendering than by Proust’s creation. One has revealed to me something and there is no revelation in the other… [You have] a supreme faculty akin to genius…’ The Scott Moncrieff translation is widely seen as a literary masterpiece in its own right, and he is considered one of the great translators into English of the twentieth century….. Conscious of his task of selling Proust to the English-speaking world, he did not make an exact literal translation but a poetic one—one he knew would appeal to the post-Edwardian public—and one that has been the subject of appreciation and controversy ever since.”

New York Times: “Proust Re-Englished” by Richard Howard

“The Scott Moncrieff translation, based on the muddled and incomplete text which was all he had to work from, is embalmed among us as – well, semi-classical. (One recalls E.M. Forster’s praise of it in ”Aspects of the Novel.”) I disagree with this widespread but careless approval, and would seek out any excuse to dislodge the thing from such status. The text is frequently erroneous, almost always at odds with the temper of Proust’s prose: Where the original is infallibly immediate and alive, Scott Moncrieff sounds, to me, stale and dated.”

The Guardian: “The perfect Proust translation – but not for purists” by Jean Findlay

“The first volumes of A la Recherche du Temps Perdu were printed with quantities of typesetter errors; Proust’s elliptical sentences were hard to follow and his handwritten annotations on top of the typescript indecipherable in places. Scott Moncrieff not only understood Proust on a personal and cultural level, he had also worked in a newspaper office and knew how typesetter errors occurred. Despite having no access to the original manuscript, Scott Moncrieff had to be both the translator and, in many cases, the interpreter, using guesswork and intuition to find the right word or probable meaning. Nor did Scott Moncrieff have the time for slavish dedication to accuracy. He took on an enormous workload, including translations of Stendhal, Abelard and Heloise, and Pirandello, so as to feed “nine hungry nephews and nieces”. With one brother dead and the other improvident, he provided for their education and medicine…. [I]f you want to read the Proust that Proust saw published, that influenced Virginia Woolf and James Joyce, that is all of one piece and interpreted by someone as close to Proust’s sensibilities, education and experience as you can get, then you must read the Scott Moncrieff translation.”

Grand Street: “Translating Proust” by Terence Kilmartin

Kilmartin says Scott Moncrieff’s work was hampered by several disadvantages. For one thing, the first volume of his English translation was published before the last volume was published in France. “The complexities of the opening pages of the novel are especially difficult to decipher without the hindsight provided by the later volumes.” Another disadvantage was the “faultiness” of the French texts Scott Moncrieff had to work with. But also: “Scott Moncrieff’s knowledge of French was far from perfect. There is evidence of this throughout the novel—signs of haziness and uncertainty that in a less ingenious and resourceful translator would have been crippling. Time and again he fails to recognize quite ordinary set expressions. One finds him translating literally when English equivalents could and should have been found. We have, for instance, the Duc de Guermantes telling Swann that he is ‘as strong as the Pont Neuf’ instead of ‘as sound as a bell.’ … [C]areless or ignorant misreadings can sometimes distort the meaning of a whole passage or even make Proust say the opposite of what he intends…. When all this is said, however, it is extraordinary how successful Scott Moncrieff was…. [he] tried as a rule to stay as close as possible to the French text.”

Oxford University Press Blog: “Translating Proust Again” by Brian Nelson

“This translation was monumental in its scale and in many ways admirable in its realization. Moncrieff had a fine ear for the cadences of Proust’s prose, and a considerable talent for elegant phrasing. But his language dated over time, especially in dialogue, and from the beginning he was prone to tamper with the text, through embellishment or the heightening of language. The reservation most commonly voiced about his translation, indeed, is that it changed Proust’s tone. He tended to make Proust sound precious and flowery, whereas Proust’s style is not in the least affected or ornate. His prose is precise, rigorous, exact.”

Translation and Literature: “Scott Moncrieff s First Translation” by Peter France

“Charles Kenneth Scott Moncrieff (1889-1930) is one of the most visible of English-language translators. His virtually single-handed translation of Marcel Proust’s A la recherche du temps perdu, done in a mere eight years from 1921 to 1929, probably had almost as great an impact on English-speaking culture as Constance Garnetťs work on the Russian novel. It has been criticized (as inaccurate, too flowery, dated, etc.) and twice revised, but it survives to compete effectively with the more recent six-handed Penguin version.”

Boston Review: “Style over Substance: On Translating Proust” by Leland de la Durantaye

“There is always a tension in translation between the spirit and the letter, between conveying things we might call tone, mood, feel, or music, and being as literally faithful to the original as possible. Moncrieff excelled at both. He created a rich and recognizable style that became, for English readers, Proust. Because the translation was the only one in existence for so very long, it naturally became closely intertwined with the fate of the work in the English-speaking world…. Moncrieff gave the book’s opening section the heading ‘Overture.’ If we turn to the other translations we find no such heading…. This is not a sign that Moncrieff was a poor translator, but it is a sign that he was a very free one, ready and willing to depart from Proust’s text where he deemed it desirable.”

New York Times: “The Shape of Time” by Peter Brooks

“Scott Moncrieff may be pardoned for thinking of the early parts of the novel as a kind of series of tone poems, along with some purplish passages, which were his forte. What he couldn’t know was the rigorous architecture of the novel as a whole.”

The New York Review: “Kilmartin’s Way” by Roger Shattuck

“[T]he ‘old’ translation (unretouched Moncrieff followed by either Blossom or Mayor) works remarkably well. You need not throw away the edition in which you have read Proust, or still hope to read him, in the hope of obtaining the real thing that has been unavailable all these years. Moncrieff was a pro with staying power.”

The Common: “On Translation, Proust, and Advice for Young Poets: an Interview with Gregory Rabassa” by S. Tremaine Nelson

“SN: Did you read Proust in French originally? GR: Of course! SN: Which English translation do you recommend? GR: Moncrieff’s all right. He was criticized for the title. Moncrieff’s gesture was to throw ‘Remembrance of Things Past’ into the title. People who criticized him read too frivolously, people who hadn’t read Shakespeare’s 30th sonnet, ‘When to the sessions of sweet silent thought I summon up remembrance of things past.’ If you read the rest of the sonnet, it’s a pocket version of Proust’s novel, and Moncrieff saw that. Ramon and Proust. That was what switched me from being a chemistry and physics major to being a language major.”

From the Note on the Translation by Terence Kilmartin in the Scott Moncrieff / Kilmartin edition:

“A general criticism that might be levelled against Scott Moncrieff is that his prose tends to the purple and the precious—or that this is how he interpreted the tone of the original…. [I]n his efforts to reproduce the structure of those elaborate sentences with their spiralling subordinate clauses, not only does he sometimes lose the thread but he wrenches his syntax into oddly un-English shapes: a whiff of Gallicism clings to some of the longer periods, obscuring the sense and falsifying the tone. A corollary to this is a tendency to translate French idioms and turns of phrase literally, thus making them sound weirder, more outlandish, than they would to a French reader.”

From the Note by D. J. Enright on his revised translation:

“C. K. Scott Moncrieff excelled in description, notably of landscape and architecture, but he was less adroit in translating dialogue of an informal, idiomatic nature…. And some further intervention was prompted by Scott’ Moncrieff’s tendency to spell out things for the benefit of the English reader: an admirable intention (shared by Arthur Waley in his Tale of Genji), though the effect could be to clog Proust’s flow and make his drift harder to follow.”

From the General Editor’s Preface by Christopher Prendergast:

“There was indeed much to be corrected in Scott Moncrieff, on a scale from the trivial to the egregious.”

From the Translator’s Introduction by Lydia Davis to the Penguin translation:

“Much as one may argue with the specifics of Moncrieff’s decisions, however, his monumental work remains the standard by which all succeeding translations of Proust will be judged. Within the limitations of his approach, which was in part conditioned by his time and cultural milieu, Moncrieff’s ambition, to remain faithful to the shape of the Proustian sentence and the order in which it unfolded, and to create a rhythmic, coherent, eloquent text in English, was impressively fulfilled in Swann’s Way. His ear was for the most part sensitive, his handling of the language adroit, his mistakes in interpretation relatively few, given the sheer number of pages he translated.”

From the introduction by William C. Carter to his revision of the Scott Moncrieff translation:

“Part of the reason for the book’s success is Charles Kenneth Scott Moncrieff’s extraordinarily fine English translation of the first six parts, generally regarded as the best rendering of any foreign work into the English language…. Harold Bloom observes that Scott Moncrieff made it possible for In Search of Lost Time to become ‘widely recognized as the major novel of the twentieth century.’”

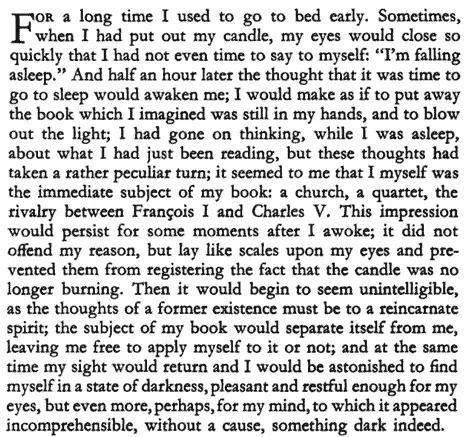

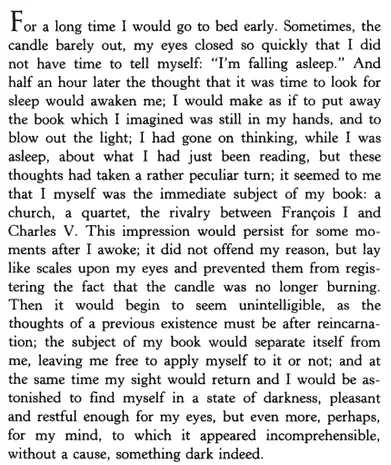

Extract from the Scott Moncrieff translation of In Search of Lost Time (Remembrance of Things Past)

Get the Penguin Classics Scott Moncrieff translation of Remembrance of Things Past

Volume 1. Contains "Swann's Way" and "Within a Budding Grove". The translations are from 1922 and 1924, respectively.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780241610510, 1072 pages).

Get the Penguin Classics Scott Moncrieff translation of Remembrance of Things Past

Volume 2. Contains "The Guermantes Way" and "Cities of the Plain". The translations are from 1925 and 1927-9, respectively.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780241610527, 1200 pages).

Get the Penguin Classics Scott Moncrieff translation of Remembrance of Things Past

Volume 3. Contains "The Captive", "The Sweet Cheat Gone" and "Time Regained". The translations are from 1929, 1930, and 1931, respectively. "Time Regained" was translated by Stephen Hudson.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780241610534, 1072 pages).

Get the Penguin Classics Scott Moncrieff translation of Remembrance of Things Past

Volume 1. Contains "Swann's Way" and "Within a Budding Grove". The translations are from 1922 and 1924, respectively.

Available as an ebook (ISBN 9780241205938).

Get the Penguin Classics Scott Moncrieff translation of Remembrance of Things Past

Volume 2. Contains "The Guermantes Way" and "Cities of the Plain". The translations are from 1925 and 1927-9, respectively.

Available as an ebook (ISBN 9780241205952).

Get the Penguin Classics Scott Moncrieff translation of Remembrance of Things Past

Volume 3. Contains "The Captive", "The Sweet Cheat Gone" and "Time Regained". The translations are from 1929, 1930, and 1931, respectively. "Time Regained" was translated by Stephen Hudson.

Available as an ebook (ISBN 9780241205976).

Who was Terence Kilmartin?

Terrence ‘Terry’ Kevin Kilmartin was a translator and the literary editor of The Observer. He was born in Ireland and moved to England as a child. In addition to reworking Remembrance of Things Past, he compiled A Guide to Proust (originally published in 1983, now out of print but included in some versions of the novel—see below).

» An address read at the memorial service for Terence Kilmartin

About the Kilmartin version of Remembrance of Things Past

Kilmartin’s version is an edit of Scott Moncrieff’s existing English translation, except that Volume 7 was translated from French by Andreas Mayor in 1970.

Grand Street: “Translating Proust” by Terence Kilmartin

“Roger Shattuck…rebuked me very severely for failing to change the overall title…. I was indeed in favor of such a change, but allowed myself to be overruled by the publishers. I do not find it quite such a crucial issue as Shattuck and others do. Still, on balance I would have preferred to re-christen the novel In Search of Lost Time, even though the English phrase lacks the specific gravity of the French and misses the double meaning of temps perdu: time “wasted,” as well as “lost.”

This version includes a note on the translation, explanatory endnotes in each volume, addenda, and synopses.

Volume titles:

- Swann’s Way

- Within a Budding Grove

- The Guermantes Way

- Cities of the Plain

- The Captive

- The Fugitive

- Time Regained

From the “Note on the Translation” by Kilmartin:

He says that the French edition Scott Moncrieff was using was “notoriously imperfect” as a result of “Proust’s methods of composition,” which were chaotic and resulted in published books plagued by “errors, misreadings and omissions.” In 1954, the painstakingly revised and “virtually impeccable” Pleiade edition was published (in French). The differences are “sometimes considerable.” His version thus updates Moncrieff’s text to match the revised French source. He includes volume 7 as translated by Andreas Mayor, who was working with the revised French source. Kilmartin also corrects some mistakes in Scott Moncrieff’s translation, even making “extensive alterations”, but avoiding “officious tinkering.”

The Guardian: “The perfect Proust translation – but not for purists” by Jean Findlay

“After Proust died his brother Robert, a medical doctor, who himself died 13 years later, and Proust’s publishers, Gallimard, began work on a new version. It brought together all the notes they had found among the manuscripts. Proust would insert pieces of paper by way of revisions, and these gummed-on “paperoles” would often fall off. Gallimard and Robert Proust painstakingly reinserted these bits of sentences where they thought they ought to be. The result was an even longer novel: they added 300,000 words to the original 12 volumes. This “definitive version” was published by Gallimard in the 1950s, and reworked into Scott Moncrieff’s translation in the 1980s by Terence Kilmartin.”

From the General Editor’s Preface by Christopher Prendergast:

“Readers of Proust in English translation have been well served, above all by two truly heroic figures: first, C. K. Scott Moncrieff, and subsequently, Terrence Kilmartin. In relation to his own predecessor, Kilmartin… modestly billed his own effort as a ‘revision’ of Scott Moncrieff’s majestic, if in certain respects flawed, production…. [In terms of style,] Kilmartin’s description of his project as a ‘revision’ was excessively modest. It is in fact in very many ways a rewriting based on a quite different conception of the language and style of the novel as a whole.” Prendergast says Kilmartin’s goal was not to foreignize but to naturalize the language of the translation “to create for the reader the sense that he or she is reading a text as if it had been ‘originally’ written in the guest language.”

New York Times: “Proust Re-Englished” by Richard Howard

“Within the limits of his corrective enterprise, Mr. Kilmartin has done a conscientious and illuminating job. I can barely imagine the skills – beyond the dreams of dentistry – which such a labor of reconstruction must have demanded…. Major and minor, Mr. Kilmartin’s revisions occur almost sentence by sentence, always with great pertinacity…. He also offers at the end of each huge volume a valuable thematic synopsis, as well as a limited but extremely useful series of notes to explain literary and historical references -and inconsistencies – which occur throughout the text. Thirty notes for each thousand pages of a work published half a century ago is a modest enough apparatus, but an immediately helpful one, and I believe all new readers of Proust in English are in an inestimably advantageous position compared with their predecessors.”

The New York Review: “Kilmartin’s Way” by Roger Shattuck

“Definitive it is not. Vastly improved, yes. I take my hat off to Kilmartin for accepting the thankless task of cleaning up after a great translator, knowing that he would have to take the blame for all remaining weaknesses and would receive little credit for his contributions.”

Grand Street: “Translating Proust” by Terence Kilmartin

“[I]t was only the impending expiry of the Scott Moncrieff copyright that persuaded the publishers to initiate a revision of the entire text. I approached the task with some trepidation. On the one hand, I was warned that my tinkering would be regarded as lese-majeste if not sacrilege. On the other, I knew there were extremists who considered that nothing less than a complete re-translation could ever do proper justice to Proust…. As I worked my way through [Scott Moncrieff’s] text, I found myself alternating between delighted admiration of his elegant fluency and exasperation with his clumsy fallibility, his bowdlerising, archaising, prettifying.”

The New York Review: “Kilmartin’s Way” by Roger Shattuck

“Kilmartin’s ‘fix’ of Moncrieff has not caused deterioration or breakdown…. He was wise enough not to tinker idly and to keep repairs to a minimum. Kilmartin peered at or listened to every line of The Search. Small readjustments turn up everywhere, not just in sudden clusters.”

On the Translation of Volume 7 (Time Regained) by Andreas Mayor:

The Paris Review: “I have I Have Gone to Bed Early: Translating Proust” By Dan Piepenbring

Richard Howard said, regarding Mayor’s volume 7: “It was so good that there were plans to commission Mayor to do all the preceding parts, but then he died too.”

The New York Review: “Kilmartin’s Way” by Roger Shattuck

“Mayor, having displaced his rivals, also prepared notes for the revision of all Moncrieff’s version. He died before he could do the work. Using Mayor’s notes as well as comments garnered from critics who had discussed the translation, Kilmartin revised everything except Mayor’s version of the last volume…. Since its appearance a decade ago, Andreas Mayor’s translation of Time Regained has been judged the only one of the three to match Moncrieff’s sustained performance.

Reading Proust: Finding by Stephen Fall

“Random House commisioned [sic] a new version by Frederick Blossom under the title of The Past Recaptured. It was Prof. Blossom’s version that I read and reread many years ago, and I wouldn’t wish it upon anyone. Sydney Schiff’s translation apparently wasn’t highly regarded, either, for an entirely new translation by Andreas Mayor was commissioned and published in 1970. It is basically Mayor’s prose that appears in the Modern Library edition today, lightly edited by Kilmartin and Enright. There are wildly varying opinions of Mayor’s Time Regained, whether he restored Proust from Schiff’s depredations, or whether his work was a depredation in its own right.”

Bookforum: “Ruminations in an Emergency: A New Translation of Proust’s Late Masterpiece” by Rebecca Ariel Porte

To solve the conundrum of Time Regained, the Modern Library editors chose to use the work of Andreas Mayor, which was based on the 1954 Pléiade edition of the novel and often colored by Mayor’s heavy editorial hand, which tended to omit in places and, like Moncrieff’s translation, elaborate on or simplify Proust’s work according to its own standards.

Extract from the Kilmartin version of Remembrance of Things Past

Get the Vintage Scott Moncrieff and Kilmartin translation of Remembrance of Things Past

Volume I: Contains "Swann's Way" and "Within a Budding Grove". Contains a note on the translation, notes, addenda, and a synopsis.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780394711829, 1056 pages).

Get the Vintage Scott Moncrieff and Kilmartin translation of Remembrance of Things Past

Volume II: Contains "The Guermantes Way" and "Cities of the Plain". Includes notes, addenda, and a synopsis.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780394711836, 1216 pages).

Get the Vintage Scott Moncrieff and Kilmartin translation of Remembrance of Things Past

Volume III: Contains "The Captive", "The Fugitive", and "Time Regained". Time regained translated by Andreas Mayor. Includes notes, addenda, and a synopsis.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780394711843, 1152 pages).

Get the Vintage Scott Moncrieff and Kilmartin translation of Remembrance of Things Past

Three-volume paperback box set. Out of print, but you may be able to find a copy using the links below.

Available as a paperback box set (ISBN 9780394712437, 3365 pages).

Who was D.J. Enright?

Dennis Joseph Enright was a British “Man of Letters.”

» More about DJ Enright at the British Council

About the Enright version of In Search of Lost Time

Enright’s version is an edit of Kilmartin’s version of Scott Moncrieff’s existing English translation (not a new translation from French). The title page of the current Modern Library edition says “Translated by C.K. Scott Moncrieff and Terence Kilmartin, revised by D. J. Enright.”

The title was updated to In Search of Lost Time for the first time.

Volume titles:

- Swann’s Way

- Within a Budding Grove

- The Guermantes Way

- Sodom and Gomorrah

- The Captive and The Fugitive

- Time Regained + A Guide to Proust

The introduction by Richard Howard in volume 1 introduces new readers to Proust and Proust to his new readers, addressing both, in turn, as ‘you’. (I find this a bit strange.)

Volume 6 contains “A Guide to Proust” compiled by Terence Kilmartin and revised by Joanna Kilmartin. The guide contains a foreword and indexes of characters, persons, places, and themes. This guide was also previously published in 1983 as “A Reader’s Guide to the Remembrance of Things Past.”

Each volume contains a biographical note, notes on the translation, a synopsis, and endnotes. Sometimes there are textual addenda.

From the “Note on the Translation” by Terence Kilmartin:

He says that the French edition Scott Moncrieff was using was “notoriously imperfect” as a result of “Proust’s methods of composition,” which were chaotic and resulted in published books plagued by “errors, misreadings and omissions.” In 1954, the painstakingly revised and “virtually impeccable” Pleiade edition was published (in French). The differences are “sometimes considerable.” His version thus updates Moncrieff’s text to match the revised French source. He includes volume 7 as translated by Andreas Mayor, who was working with the revised French source. Kilmartin also corrects some mistakes in Scott Moncrieff’s translation, even making “extensive alterations”, but avoiding “officious tinkering.”

From the Note by D. J. Enright on the Revised Translation:

“The present revision or re-revision has taken into account the second Pleiade edition…. [which] clears up some long-standing misreadings.”

From the General Editor’s Preface by Christopher Prendergast to the Penguin translation:

“Kilmartin had the advantage of working from the far more reliable 1954 Pleiade edition…. [The] 1987 Pleiade edition… formed the basis of a further projected revision by Kilmartin, which, owing to ill-health, he passed on to D.J. Enright (Enright calls it a ‘re-revision’).”

Blurb by Richard Howard

“[T]his ultimate revision of the primary version affords the surest sled over the ice fields as well as the most sinuous surfboard over the breakers of Proustian prose, an invaluable and inescapable text.”

The Guardian: “Reviving the dread deity” by Paul Davis

“[T]he only previous translation of the novel into English, by CK Scott Moncrieff, showered Proust’s text in “cascades of Edwardian purple prose”, some but not all of them staunched by Terence Kilmartin and DJ Enright in the “fully revised” version now reissued by Vintage to compete with [the Penguin translation]…. For those without French considering setting out on the Proustian journey, the Moncrieff/ Kilmartin/Enright translation, remains, in my view, the best available reading text.”

Independent: “Forever in search of lost truth: Gabriel Josipovici on the problems of translating Proust, and the new revision by D J Enright”

“Enright’s hand has wisely been extremely light, for Kilmartin had, by and large, done an excellent job. He had corrected most of Moncrieff’s blunders… and had generally tried to make the tone as colloquial as that of the originals…. There are places, though, where Kilmartin has failed to spot a lapse by Scott Moncrieff and Enright has not acted either…. There are also places where Kilmartin seems to have gone more wrong than his predecessor, and where Enright has still let things stand…. It is of course easy for a reviewer to carp. Enright has had a go at the well-nigh impossible closing sentence of the novel and has not, to my mind, done any better with it than his predecessors; on the other hand, there are here and there many tiny touches where, like Kilmartin before him, he has helped make the translation more colloquial, flexible and in tune with the great original.”

The Yale Review: “Loaf or Hot-Water Bottle: Closely Translating Proust” by Lydia Davis

“[N]either Kilmartin nor Enright – as far as I can see from a number of close comparisons along the way – was as good a stylist as Moncrieff, so that although the latest version is undoubtedly more correct than Moncrieff’s, the newly rendered passages are not always up to the standard of the original translation. The text throughout could also be brought much closer to the French. There is still a great deal of “padding” in the revised versions. Not all the archaicisms have been eradicated – you will still come upon such expressions as “I bethought myself” – and not all the mistakes have been corrected.”

Extract from the Enright version of In Search of Lost Time

Get the Everyman's Library Scott Moncrieff and Enright translation of In Search of Lost Time

Volume 1: Contains "Swann's Way" and "Within a Budding Grove (Part One)".

Available as a hardcover (ISBN 9781841598963, 700 pages).

Get the Everyman's Library Scott Moncrieff and Enright translation of In Search of Lost Time

Volume 2: Contains "Within a Budding Grove (Part Two)" and "The Guermantes Way".

Available as a hardcover (ISBN 9781841598970, 900 pages).

Get the Everyman's Library Scott Moncrieff and Enright translation of In Search of Lost Time

Volume 3: Contains" Sodom and Gomorrah" and "The Captive".

Available as a hardcover (ISBN 9781841598987, 900 pages).

Get the Everyman's Library Scott Moncrieff and Enright translation of In Search of Lost Time

Volume 4: Contains "The Fugitive" and "Time Regained".

Available as a hardcover (ISBN 9781841598994, 700 pages).

Get the Everyman's Library Scott Moncrieff and Enright translation of In Search of Lost Time

Four-volume hardcover boxed set.

Available as a hardcover box set (ISBN 9781857152500, 3152 pages).

Get the Vintage Classics Scott Moncrieff and Enright translation of In Search of Lost Time

Volume 1: "Swann's Way". UK version. Includes a biographical note, a note by Terence Kilmartin on the translation, a note by D.J. Enright on the translation, endnotes, and a synopsis.

Available as a paperback (ebook also available) (ISBN 9780099362210, 544 pages).

Get the Vintage Classics Scott Moncrieff and Enright translation of In Search of Lost Time

Volume 2: "Within a Budding Grove". UK version. Includes endnotes, addenda, and a synopsis.

Available as a paperback (ebook also available) (ISBN 9780099362319, 656 pages).

Get the Vintage Classics Scott Moncrieff and Enright translation of In Search of Lost Time

Volume 3: "The Guermantes Way". UK version. Includes endnotes, addenda, and a synopsis.

Available as a paperback (ebook also available) (ISBN 9780099362418, 720 pages).

Get the Vintage Classics Scott Moncrieff and Enright translation of In Search of Lost Time

Volume 4: "Sodom and Gomorrah". UK version. Includes endnotes, addenda, and a synopsis.

Available as a paperback (ebook also available) (ISBN 9780099362517, 656 pages).

Get the Vintage Classics Scott Moncrieff and Enright translation of In Search of Lost Time

Volume 5: "The Captive" and "The Fugitive". UK version. Includes endnotes, addenda, and a synopsis.

Available as a paperback (ebook also available) (ISBN 9780099362616, 832 pages).

Get the Vintage Classics Scott Moncrieff and Enright translation of In Search of Lost Time

Volume 6: "Time Regained" and "A Guide to Proust". UK version. Includes endnotes and a synopsis.

Available as a paperback (ebook also available) (ISBN 9780099362715, 704 pages).

Get the Modern Library Scott Moncrieff and Enright translation of In Search of Lost Time

Volume I: "Swann's Way". Introduction by Richard Howard. Includes a biographical note, a note by Terence Kilmartin on the translation, a note by D.J. Enright on the translation, endnotes, and a synopsis.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780375751547, 656 pages).

Get the Modern Library Scott Moncrieff and Enright translation of In Search of Lost Time

Volume II: "Within a Budding Grove". Contains a biographical note, a note by Terence Kilmartin on the translation, a note by D.J. Enright on the translation, endnotes, addenda (maybe), and a synopsis.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780375752193, 784 pages).

Get the Modern Library Scott Moncrieff and Enright translation of In Search of Lost Time

Volume III: "The Guermantes Way". Contains a biographical note, a note by Terence Kilmartin on the translation, a note by D.J. Enright on the translation, endnotes, addenda, and a synopsis.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780375752339, 864 pages).

Get the Modern Library Scott Moncrieff and Enright translation of In Search of Lost Time

Volume IV: "Sodom and Gomorrah". Contains a biographical note, a note by Terence Kilmartin on the translation, a note by D.J. Enright on the translation, endnotes, addenda, and a synopsis.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780375753107, 784 pages).

Get the Modern Library Scott Moncrieff and Enright translation of In Search of Lost Time

Volume V: "The Captive" and "The Fugitive". Contains a biographical note, a note by Terence Kilmartin on the translation, a note by D.J. Enright on the translation, endnotes, addenda, and a synopsis.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780375753114, 992 pages).

Get the Modern Library Scott Moncrieff and Enright translation of In Search of Lost Time

Volume VI: "Time Regained" and "A Guide to Proust". Contains a biographical note, a note by Terence Kilmartin on the translation, a note by D.J. Enright on the translation, endnotes, and a synopsis.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780375753121, 784 pages).

Get the Modern Library Scott Moncrieff and Enright translation of In Search of Lost Time

Six-volume paperback boxed set.

Available as a paperback box set (ISBN 9780812969641, 4864 pages).

Get the Modern Library Scott Moncrieff and Enright translation of In Search of Lost Time

Complete and unabridged ebook bundle.

Available as a combined ebook (ISBN 9780679645689).

What’s in Post 2?

- Translations by the Penguin team, a revision of the Scott Moncrieff translation by William C. Carter, and a new translation by Brian Nelson edited by Adam Watt.

- Other information and resources (guides and biographies).

If you just want a quick-and-dirty recommendation on which translation to choose, jump to the Conclusion of Post 2.

What do you think of the Scott Moncrieff translation? Unparalleled classic, or time to move on? Let us know in the comments!