Which English translation of The Nine Cloud Dream should I read?

So, you want to read a classic Joseon Dynasty dream-journey “novel” set in a fictional version of Tang Dynasty China? A towering and influential masterpiece in Korea, it’s still relatively obscure in the West, although that may be changing: the 2019 Penguin Classics edition puts Kim Man-jung (surname Kim, pen name Sop’o) on the shelf with Dostoevsky and Cervantes.

It might remind you of the similarly framed Chinese classic, The Dream of the Red Chamber, the aristocratic Japanese Tale of Genji, or the enlightenment tale Siddhartha. Comparisons have also been made to the didactic journey Pilgrim’s Progress and the ironic adventure Don Quixote.

Supposedly the author wrote The Nine Cloud Dream during a period of political exile to entertain his mother. You, too, will be entertained. And perhaps enlightened as well.

TLDR?

If you just want a quick-and-dirty recommendation on which translation to choose, jump to the conclusion.

The Nine Cloud Dream: Translations in English

There have been three. One is out of print.

The Nine Cloud Dream: Other Translations

Fenkl’s introduction mentions an unpublished 1973 translation by The English Student Association of the Department of English Language and Literature at Ewha Women’s University under the supervision of Kathleen Crane titled The Nine Cloud Dream.

What’s the title? Kuunmong vs. The Cloud Dream of the Nine vs. A Nine Cloud Dream vs. The Nine Cloud Dream vs. A Dream of Nine Clouds

Kuunmong, literally meaning “nine cloud dream”, is the Korean title. Asian languages don’t have articles like ‘a’ and ‘the’, and in the three-words-no-spaces titles in Korean and Chinese, there’s no word like ‘of’ to indicate any relationship between the words. Translators thus have different ideas about how to best represent the title in English.

In his introduction to A Nine Cloud Dream, Rutt says “The cloud in the title is often understood to be an adjective describing the dream, but in view of the significance of the idea of the dream in novel titles of this genre, such an adjective would be otiose. On the other hand, the cloud as a symbol of the insignificance of human life is to be found in the Analects of Confucius, and in Buddhist usage the word ‘cloud’ can mean a devotee, especially a wandering monk. Since the ‘nine’ of the title unquestionably refers to the nine chief characters who transmigrate from the life of Buddhist devotees to the dream of worldly life, it seems best to take the word ‘cloud’ as a substantive and understand the title as ‘a dream of nine clouds’.”

What is The Nine Cloud Dream about?

Written in the late 17th century in literary Chinese by a Korean nobleman and set in 9th-century China, this novel contrasts the satisfactions of a material life well-lived with the rules and goals of Mahayana Seon/Chan/Zen Buddhism, although there are Confucian and Taoist elements as well. The plot follows a monk who is tempted by worldly delights and ‘punished’ by being sent (along with eight beautiful women, nine people in total) to experience enormous amounts of fantastic success and easily obtained pleasure in a dream that lasts a lifetime… or no time at all.

» I posted about the plot and message of The Nine Cloud Dream on Asian Books Blog.

Richard Rutt, in the introduction to Virtuous Women, says this about the book’s message: “Kim Man-jung does not say that because the life of man is painful and cruel, it is worthless and must be transcended. He says that even at its impossibly ideal best it would be no more than a dream.”

The novel has a historico-political meaning as well as a spiritual meaning: the unruffled friendship of the eight women in Kuunmong is meant as a contrast to the conflict and strife in the court of the author’s real-life ruler, King Sukjong. Professor Francisca Cho’s analysis of the book says that fiction, unlike poetry, “was a purely private enterprise, to be shared with close friends and family rather than created for public consumption…. The private nature of fiction hence made it the safest medium of political criticism, and the novels of seventeenth and eighteenth century Korea frequently voice the discontent of the socially dispossessed.”

Philosophy Blogger Thomas Foerster isn’t convinced that the story successfully upholds Buddhist themes: “The moral of the story seems to be the anti-Buddhist moral of The Picture of Dorian Grey: ‘The only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it.‘ ” He’s definitely not the only one scratching his head as to how the main character’s dream life is supposed to teach him a moral lesson.

Korean Studies: “The Structure of the Kuun mong” by Chang Sik Yun (PhD in comparative literature, Princeton University, 1972)

“The structural device of a dream vision employed in Kim Manjung’s (1637-1692) Kuun mong [A dream of nine clouds] is intended to embody the Buddhist tenet that earthly pleasures are as illusory as a dream…. By adopting the structural device of a dream vision Kim Manjung sets himself the artistically impossible task of creating a romance within the framework of an antiromance without molding these antithetical entities into an artistically viable whole…. Insofar as the content of the hero’s dream constitutes virtually the entire work, the content of the dream might be expected to manifest the philosophic precepts implicit in the dream-vision framework. In fact, this is hardly the case…. By way of contrast, we might consider Don Quixote, in which the two levels of mimesis, interacting as they do in ironic relationships, are unified in the terms of characters and events in the experiential world.”

Kurodahan Press: “Introduction to Kuunmong: The Cloud Dream of the Nine” by Susanna Fessler

“[A]lthough this is arguably a didactic novel, it is unlikely that the reader is meant to identify directly with either character [the monk or the successful man]. Much ink has been spilt on the unrealistic nature of these characters and the consequent poor value of the novel, but I believe the reader really need not concern himself with this. In the end this lack of verisimilitude is of little consequence; one can easily suspend disbelief and indulge in the adventure, as one does when watching a contemporary Hollywood film. In other words, the modern reader should not walk away from this novel in disbelief at the behavior of the characters, but rather should look beyond their surface behavior to the values that drive them. It is there that the message of the work lies. The entertaining flourishes are merely a sweet indulgence to help the more serious question take hold.”

Douglas Penick, in his article for The Buddhist Review: Tricycle, says that reading is like being temporarily reincarnated: “To read is to find oneself, at least partially, disembodied and reborn, to live not exactly in this world but in a different realm. In this altered dimension, the senses still function and the mind is engaged. But here we can move from place to place, time to time, being to being. In the domain of reading, we can explore what is unknown, what is frightening, what is desirable.”

Richard Rutt, in the introduction to Virtuous Women, says The Nine Cloud Dream was written about women for a woman. While men could lead successful lives according to the ideals of Confucianism, “For women, the comforts of Buddhism were of greater importance.… Women wanted to be modest, pure, obedient, ceremonious, and noble-minded. They were also jealous, ambitious, and clever. Some were ignorant, but many were accomplished and well-educated. The tension between the formal role expected of them by society and the spiritual forces within them combined to make women more interesting subjects for fiction than men were.”

How are the poems in The Nine Cloud Dream translated?

Translating prose is hard. Translating poetry is impossible! Nevertheless, we expect translators to put something onto the page for us. Here’s the Willow Song, the first poem in the novel:

Gale:

Willows hung like woven green,

Veiling all the view between,

Planted by some fairy free,

Sheltering her and calling me.Willows, greenest of the green,

Brushing by her silken screen,

Speak by every waving wand,

Of an unseen fairy hand.

Rutt:

The willows shimmer like green silk,

The long fronds brush the painted pavilion.

Why should you plant them so carefully?

The mere sight of such trees stirs the senses.Why are the willows so green?

The long fronds brush the silken pillars.

Why should you want to pluck them?

The mere sight of such trees stirs the heart.

Fenkl:

The green silky willow, its slender wands

veiling the bright pavilion—

Why have you planted it?

Was it your exquisite taste?The long willow drapes, their deep green hue

’round the radiant pillar—

Take care and do not break them,

for they are fragile and they move my heart.

Gale made the poems rhyme. Since Rutt and Fenkl both mention green, silk, pillar, pavilion, and heart, it would seem they stuck closer to the meaning of the original poem while using other poetic techniques to create an elegant effect.

Bonus! Translation apparently by Chang Sik Yun, from “The structure of the Kuun mong”:

Willows are green as silk,

Long boughs brush the painted pavilion.

Pray, plant them with care,

These trees are most graceful.Willows—how green and green,

Long boughs brush the beautiful pillars.

Pray, do not break them,

These trees are most affectionate.

Who was James Scarth Gale?

Born in Canada, James S. Gale was a missionary who lived in Korea for over thirty years. He translated the Bible and other Christian materials (including The Pilgrim’s Progress) into Korean. He also published Korean language reference materials in English and had a keen interest in Classical Chinese.

About the Gale translation of The Nine Cloud Dream

- This translation is in the public domain.

- The text is illustrated with 16 woodcut illustrations.

- There are some explanatory notes.

- The text is split up into 16 chapters.

- Gale’s poems rhyme in English.

- Gale’s character names are Korean.

- The introduction has spoilers (in section IV).

Kurodahan Press: “Introduction to Kuunmong: The Cloud Dream of the Nine” by Susanna Fessler

Gale’s translation is “relatively complete and accurate” with the exception of the poetry and transliteration of names. “Also, in the tradition of early translations from Asian literature, Gale omits certain short passages at his discretion. For example, when Kim Manjung quotes a short passage from the Diamond Sutra in the last scene, Gale omits it. In the end none of this much changes the content of the book. Gale’s translation is in the spirit of the original, and continues to bring this classic to a western audience.”

Asymptote: Review of The Nine Cloud Dream by Katherine Beaman

Gale’s translation strategy is influenced by his own background, and his perception of his audience. “James Scarth Gale did not expect his readers to have knowledge of Buddhist symbolism, the canon of Chinese poetry, or the relationship between The Nine Cloud Dream’s historical setting and its role as a political commentary. For instance, rather than directly referring to the Diamond Sutra by name, Gale attempts to summarize its philosophy for the reader. In other instances, direct allusions to such Chinese poets as Li Po are omitted outright…. Gale’s translation tends to suggest that one’s destiny is controlled by external forces, choosing wording that blames material temptations for characters’ sins…. It is easy to imagine that Gale, as a religious leader from a theological background that dictates that humans will inevitably succumb to sin and temptation, might feel a kinship with a young monk who falls short of the demands of his vows.”

Richard Rutt, in the introduction to A Nine Cloud Dream, says that “The extreme youthfulness of the hero at the time of his major exploits so disturbed Gale that he added a few years to the ages of all the characters.”

Extract from the Gale translation of The Nine Cloud Dream

Get the Kurodahan Press Gale translation of The Cloud Dream of the Nine

Original introduction by Elspet Keith Robertson Scott is included. Also included are aew introduction by Susanna Fessler and an interpretation by Francisca Cho, which can be read online at the book's page at Kurodahan Press.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9784902075038, 252 pages).

Get the Manybooks Gale translation of The Cloud Dream of the Nine

There are page numbers in brackets throughout the text, but apart from that very minor annoyance (and the egregious typo on the cover, shown here), this version is fine. Ebook is free to read online or download. Introduction by Elspet Keith Robertson Scott.

Available as an ebook.

Who was Richard Rutt?

Like James S. Gale, he was a scholar and missionary who lived in Korea for many years and studied and wrote about Korea’s language, culture, and history. He translated and published a book of Korean sijo poems. He also studied Classical Chinese and published a translation of The I Ching (Zhou Yi, The Book of Changes).

» Korea Times obituary of Richard Rutt

About the Rutt translation of The Nine Cloud Dream

- Rutt’s character names are Chinese.

- Rutt’s version has 7 chapters (not 16).

- This version re-uses the 16 woodcut illustrations from 1922.

- The introduction has spoilers.

From the translator’s preface:

“The text has not been annotated, because the book is intended for the general reader’s enjoyment. Explanatory phrases have been inserted into the translation where it seemed necessary to illuminate what would otherwise be merely mystifying allusions. The illustrations to Kuunmong are taken from Gale’s The Cloud Dream of the Nine (London 1922), which contains a picture for each of the sixteen chapters.”

Asymptote: Review of The Nine Cloud Dream by Katherine Beaman

Rutt’s introduction highlights the role of women in society, something the author clearly grappled with. “Many of the women in The Nine Cloud Dream have conversations about poetry and friendships which are unrelated to their relationship with Shao-Yu. They make vows not only to him, but also, and often in a way that takes precedence, to each other. Although these women cannot by any stretch of the imagination be said to be liberated, Kim is critical of the way in which their livelihoods are subjected to the whims of those who are above them hierarchically…. The women in the novel often express discontent with the ways in which societal demands contradict each other, such that they are not able to fulfill their duties, yet they do not seek to subvert the structures that govern their place in society.”

Extract from the Rutt translation of The Nine Cloud Dream

Get the Royal Asiatic Society Rutt translation of A Nine Cloud Dream

This book is out of print. You may be able to find a second-hand copy using the links.

Available as a hardcover (ISBN 8995442433, 333 pages).

Who is Heinz Insu Fenkl?

He is a Korean-German professor, writer, and translator.

Penguin says: ” Heinz Insu Fenkl is a writer, editor, translator, and folklorist. His first novel, Memories of My Ghost Brother, was a PEN/Hemingway finalist. He is an associate professor of English at SUNY New Paltz. He also serves on the editorial board of Azalea: Journal of Korean Literature and Culture, and is a consulting editor for Words Without Borders. His fiction has been published in The New Yorker, and his story collection, Skull Water, is forthcoming from Graywolf Press.”

Fenkl, in the Acknowledgments section of his translation, says: “I unwittingly began my career as a translator when I tried to write down stories [my Korean maternal uncles] had told me in Korean in my seventh-grade English notebook in Germany.”

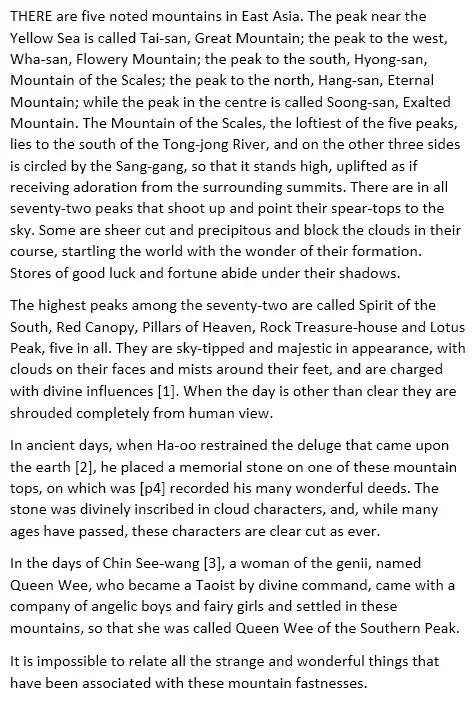

About the Fenkl translation of The Nine Cloud Dream

- Fenkl’s character names are Chinese.

- Fenkl’s version has 16 chapters.

- This version re-uses the 16 woodcut illustrations from 1922.

- The introduction has spoilers (especially in the section called “The Novel”).

From Fenkl’s introduction: To try to understand the ‘numerous challenges’ of translating this work, “imagine if a Russian novelist of the nineteenth century had written a heroic fantasy novel set in the France of the Middle Ages and furthermore wrote it in the French of that time, alluding, throughout the work, to even earlier French literature.”

Asymptote: Review of The Nine Cloud Dream by Katherine Beaman

Beaman praises Fenkl’s poetic sensibilities, which shine through even in his prose: “Fenkl’s is a novel one touches, inhales, and hears; Gale’s is a novel one observes.”

The Korea Society: Podcast episode with Heinz Insu Fenkl about translating The Nine Cloud Dream

Aired 20 February, 2019. 46 minutes.

Asian Review of Books: “Review of The Nine Cloud Dream” by John Butler

“Professor Fenkl has produced a fluent, lively and indeed elegant translation of this work, which does its author justice and skilfully navigates between avoiding self-conscious archaism (this is a 17th-century work, after all) in the tone of the book whilst at the same time using language which has not been made to sound anachronistic or too ‘modern’.”

Columbia Journal: Review of the Nine Cloud Dream by Laura Head

“Despite the difficulties, Fenkl surely succeeds. The archaisms of his language and syntax create the familiar aura of fairytale and romance perfectly suited to the story, which so marvelously mixes myth and legend….. The translator’s introduction and notes not only provide historical background for the novel but explain its complexity and increase the reader’s appreciation for it. The strength of the new translation lies not only in its supplementary material but in Fenkl’s appreciation both for his sources and his audience…. his unique approach and archaic style have resulted in a translation that evokes the awe and delight we felt as children when we first encountered a classic fairy tale. We do not just enjoy the story, we revere it.”

Tony’s Reading List: Review of The Nine Cloud Dream

“[Fenkl’s introduction] explains how he modelled the language of his text on old stories and legends, with the attention to detail extending to his choice of the Wade-Giles system of Romanisation for its more old-fashioned feel. It definitely works, as the story reads very nicely indeed, and the experience is only enhanced by his comments, copious endnotes and the informative introduction…. [The appendix] provides a brief example to show how even the Chinese characters used in the original text contain more layers of allusions, with visual clues helping contemporary readers to unearth more hidden meanings.”

Extract from the Fenkl translation of The Nine Cloud Dream

Get the Penguin Classics Fenkl translation of The Nine Cloud Dream

Introduction and notes by Heinz Insu Fenkl.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780143131274, 288 pages).

Get the Penguin Classics Fenkl translation of The Nine Cloud Dream

Introduction and notes by Heinz Insu Fenkl.

Available as an ebook (ISBN 9781524705022).

Get the Tantor Audio Fenkl translation of The Nine Cloud Dream

Running time: 8 hours. Narrated by David Shih. Visit Amazon to listen to sample.

Available as an unabridged audio CD.

Video Game Adaptation

Dream9 is a gender-flipped visual novel based on “The Cloud Dream of the Nine”. It has one female character and nine male characters. “As you proceed with the story, you encounter many hardships and you get to make many choices. The fate of the target is determined by what choice you make at the key points that will lead to different endings.”

Buddhist Literary Analysis

Get Embracing Illusion: Truth and Fiction in The Dream of the Nine Clouds by Francisca Cho Bantly

Hardcover and paperback copies seem to be out of print but are perhaps still available from the publisher.

Available as a hardcover (ISBN 9780791429693, 262 pages).

Get Embracing Illusion: Truth and Fiction in The Dream of the Nine Clouds by Francisca Cho Bantly

Available as an ebook.

What’s the best The Nine Cloud Dream translation?

All three have their advantages.

If you’re looking for a free ebook, you can read the Gale translation. Gale distorted the text to cater to its audience, but you can still get a pretty good sense of the work from reading his version.

If you want to read some commentary on women in Korea, or you’re interested in reading the other two books in the anthology, hunt down an out-of-print copy of Rutt’s Virtuous Women.

If you want a recent translation done to modern standards, go with the Penguin Classics version translated by Fenkl, which you can get as a paperback or ebook.

Already have a favorite? Let us know which one and why in the comments!