“I want to read the best English translation of the Dream of the Red Chamber!”

So you want to read the most modern of China’s Four Great Classical Novels, also known as The Story of the Stone and A Dream of Red Mansions, and you don’t read Chinese.

Beware! The old and widely available Joly translation doesn’t contain all the chapters of the original, even though it’s almost 1000 pages long!

(If what you want is a short version, check out the illustrated Real Reads version or the Wang abridgment.)

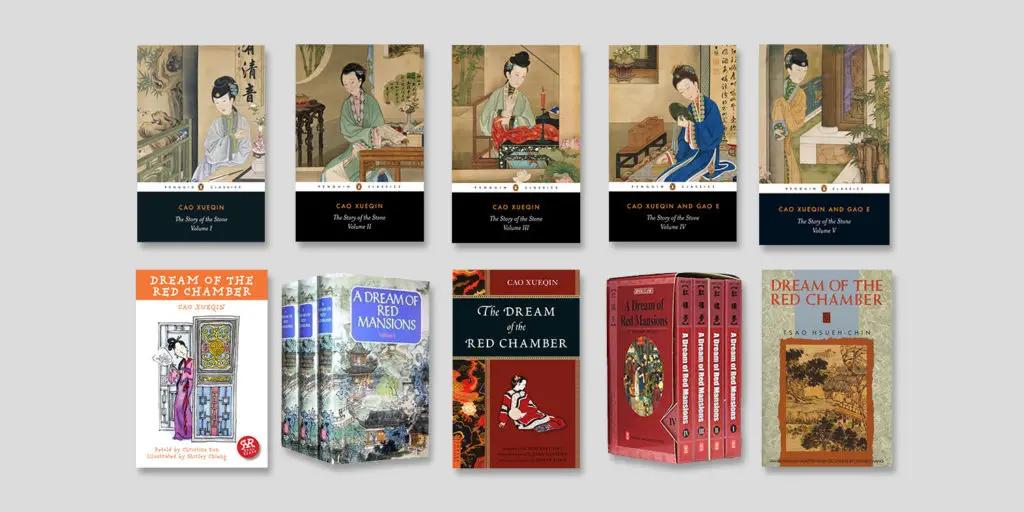

A complete translation was not available until the mid-1980s, but now you have two to choose from: the Hawkes & Minford translation published by Penguin and the Yang & Yang translation published by Foreign Languages Press.

Dream of the Red Chamber: Translations

These translations are all in print, but only two of them are complete.

- 1893 – H. Bencraft Joly (truncated)

- 1958 – Chi-Chen Wang (abridged)

- 1980 – Gladys and Hsien-Yi Yang (complete)

- 1986 – David Hawkes & Jon Minford (complete)

- 2013 – Christine Sun (adapted)

“Who wrote The Dream of the Red Chamber?”

The author of the first 80 chapters was Cao Xueqin. Scholars believe it is likely that Gao E, who worked on those chapters as editor and publisher, was the one who wrote the last 40 chapters. These are Chinese names with the family name shown first.

Sometimes the authors are listed as “Tsao Hsueh-Chin and Kao Ngo”. You may see them in the opposite order as well: “Hsueh-chin Tsao and Ngo Kao”. Those are just different spellings of the names of the authors, “Cao Xueqin and Gao E”.

“Why are there variations on the title?”

The transliteration of the Chinese title of the book is Hung Lou Meng, Heng Lou Meng, or Hong Lou Meng, which maybe literally means something like “red edifice dream”. People usually have no problem translating ‘red’ consistently. (The academic field of study devoted to examining this particular work of Chinese literature is in fact called ‘redology’.) The ‘lou’ has more than one possible interpretation, though, and Chinese does not explicitly mark nouns as singular or plural the way English does. Hence ‘mansion(s)’ and ‘chambers(s)’. Variations between ‘a’ and ‘the’ at the beginning of the title are due to the lack of any such articles in Chinese.

Why did Penguin choose to call the work The Story of the Stone, a different title altogether? Certainly it’s not an unprecedented title; it may be the one the author originally preferred, and it seems to be the one the work was originally known by. According to the introduction by David Hawkes, the original 80-chapter manuscripts (which literally were manuscripts written by hand, not printed) circulated with the title Red Inkstone’s Reannotated Story of the Stone. Red Inkstone was the nickname of an anonymous commentator who must have been close to the author. The author listed five possible titles in the text; the publisher of the expanded version of the novel chose to call it A Dream of Red Mansions. Since more people read the printed version, the work came to be known more widely by this second title.

Who was H. Bencraft Joly?

Henry Bencraft Joly studied Chinese in Beijing and started translating The Dream of the Red Chamber while serving as a representative of the British government in Macao. He died in Korea at the age of 41, leaving his literary work sadly incomplete.

About the Joly translation of The Dream of the Red Chamber

The Joly translation of The Dream of the Red Chamber contains only 56 of the 120 chapters of the original. It was originally published in two volumes in Hong Kong.

The introduction in the Tuttle edition characterizes the translation as ‘meticulous’.

“Joly did not use generalizations in translation to suit the level of Sinological knowledge of the average reader, at the expense of details in the original Chinese text. Neither did his use of the English language mask the intricacies of the use of language in the original Chinese.”

The weakness of the translation, according to Joly, was his poetry. According to Edwin H. Lowe, author of the Tuttle introduction, the weakness of the Joly translation is that a particular sentence was edited to suit Victorian sensibilities.”

Tuttle didn’t update the text much, except to correct errors and change the spelling system from Wade-Giles to Pinyin.

Extract from the Joly translation of The Dream of the Red Chamber

Get the Project Gutenberg Joly translation of The Dream of the Red Chamber (truncated)

The lovely abstract fuschia cover image is auto-generated by Project Gutenberg. To get all 56 chapters of the Joly translation, you will need to download Book I (chapters 1 to 24) and Book II (chapters 25 to 56).

Available as an ebook.

Get the Project Gutenberg Joly translation of The Dream of the Red Chamber (truncated)

The lovely abstract fuschia cover image is auto-generated by Project Gutenberg. To get all 56 chapters of the Joly translation, you will need to download Book I (chapters 1 to 24) and Book II (chapters 25 to 56).

Available as an ebook.

Get the Tuttle Joly translation of The Dream of the Red Chamber (truncated)

Truncated, only 56 chapters. Foreword by John Minford. Introduction by Edwin Lowe. Preface by H. Bencraft Joly.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780804840965, 992 pages).

Get the Tuttle Joly translation of The Dream of the Red Chamber (truncated)

Truncated, only 56 chapters. Foreword by John Minford. Introduction by Edwin Lowe. Preface by H. Bencraft Joly.

Available as an ebook (ISBN 9781462902477).

Who was Chi-Chen Wang?

He was a Chinese-American academic and writer. He was born in Shandong Province in China and attended university in the US. He translated many Chinese stories (including “The True Story of Ah Q” by Lu Xun) into English.

About the Wang translation of Dream of the Red Chamber

Wang published an abridgement in 1929. He published a 60-chapter expanded version in 1958. This version uses Wade-Giles Romanization.

Extract from the Wang translation of Dream of the Red Chamber

Get the Anchor Wang translation of Dream of the Red Chamber

Available as (ISBN 9780385093798, 329 pages).

Who were Gladys Yang and Hsien-yi Yang?

Gladys was the daughter of a British missionary living in Beijing. Hsien-yi (pinyin spelling: Xianyi) was born in Tianjin. They married after meeting at Oxford. They worked together as translators for the Foreign Languages Press in Beijing.

About the Yang & Yang translation of a Dream of Red Mansions

The translation is complete, with all 120 chapters of the original. There is an abridged version too (see below).

For names, Yang and Yang used spellings which I assume correspond to the Wade-Giles Romanization system. It’s possible that later editions of their translation switched to Pinyin, but that is pure speculation, so I assume the spellings you see in the extract below are the ones you will see in recent copies as well.

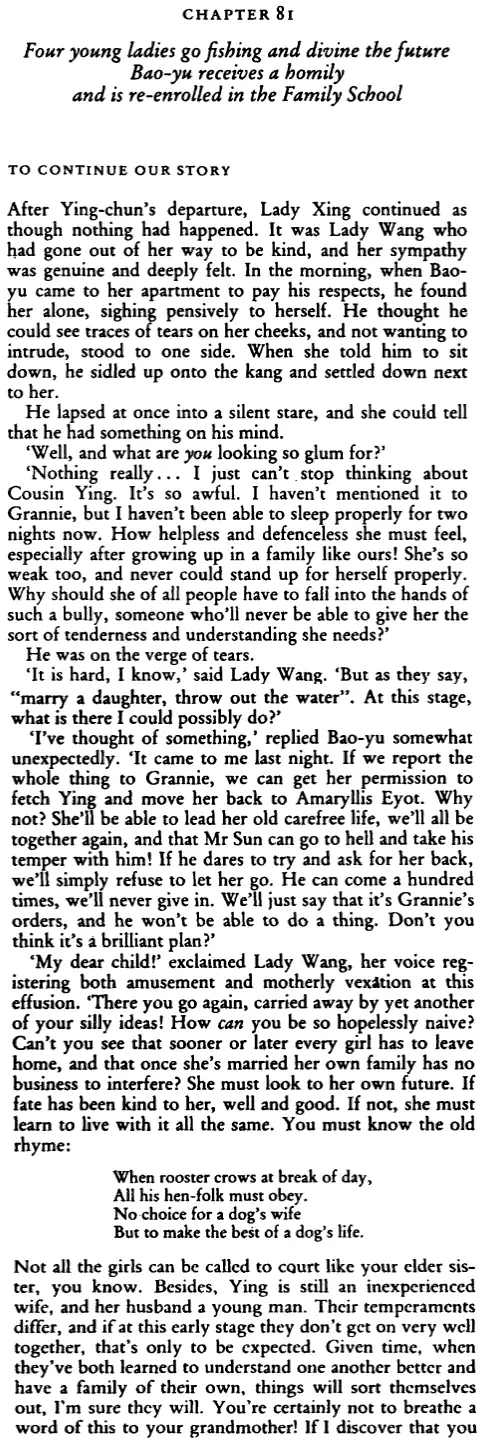

Extract from the Yang and Yang translation of a Dream of Red Mansions

Get the Foreign Languages Press Yang and Yang translation of A Dream of Red Mansions

Available as a set of four paperbacks (ISBN 9787119006437).

Get the Foreign Languages Press Yang and Yang translation of A Dream of Red Mansions

Available as a set of three hardcovers (ISBN 9787119016436).

Get the Foreign Languages Press Yang and Yang translation of A Dream of Red Mansions

A Dream of Red Mansions: Volume 1 (out of print)

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9781589635227, 644 pages).

Get the Foreign Languages Press Yang and Yang translation of A Dream of Red Mansions

A Dream of Red Mansions: Volume 2 (out of print)

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9781589635326, 736 pages).

Get the Foreign Languages Press Yang and Yang translation of A Dream of Red Mansions

A Dream of Red Mansions: Volume 3 (out of print)

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9781589635739, 620 pages).

Get the Foreign Languages Press Yang and Yang translation of A Dream of Red Mansions

A Dream of Red Mansions (abridged)

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780887271786, 499 pages).

Who are David Hawkes and John Minford?

The late Hawkes was a British translator who studied Chinese in England and China. John Minford is a British translator who has studied Chinese in England and Australia and taught in China. Hawkes was his teacher at Oxford.

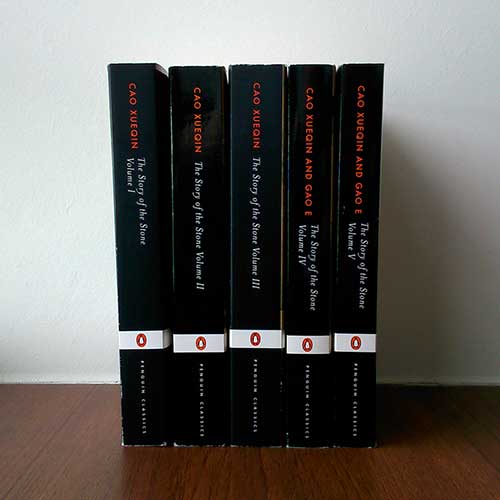

About the Hawkes and Minford translation of The Story of the Stone

The translation is complete, with all 120 chapters of the original.

For names, Hawkes & Minford used Pinyin Romanization, which is the current dominant system in China and internationally.

Extract from the Hawkes and Minford translation of The Story of the Stone

The five volumes of the Hawkes & Minford translation are titled:

- Volume 1: The Golden Days

- Volume 2: The Crab-Flower Club

- Volume 3: The Warning Voice

- Volume 4: The Debt of Tears

- Volume 5: The Dreamer Wakes

They’re all available in paperback and as ebooks (see below).

Get the Penguin Classics Hawkes and Minford translation of The Story of the Stone

The Story of the Stone: Or, The Dream of the Red Chamber, Volume I: The Golden Days

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780140442939, 540 pages).

Get the Penguin Classics Hawkes and Minford translation of The Story of the Stone

The Story of the Stone: Or, The Dream of the Red Chamber, Volume I: The Golden Days

Available as an ebook.

Get the Penguin Classics Hawkes and Minford translation of The Story of the Stone

The Story of the Stone: Or, The Dream of the Red Chamber, Volume II: The Crab-Flower Club

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780140443264, 608 pages).

Get the Penguin Classics Hawkes and Minford translation of The Story of the Stone

The Story of the Stone: Or, The Dream of the Red Chamber, Volume II: The Crab-Flower Club

Available as an ebook.

Get the Penguin Classics Hawkes and Minford translation of The Story of the Stone

The Story of the Stone: Or, The Dream of the Red Chamber, Volume III: The Warning Voice

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780140443707, 640 pages).

Get the Penguin Classics Hawkes and Minford translation of The Story of the Stone

The Story of the Stone: Or, The Dream of the Red Chamber, Volume III: The Warning Voice

Available as an ebook.

Get the Penguin Classics Hawkes and Minford translation of The Story of the Stone

The Story of the Stone: Or, The Dream of the Red Chamber, Volume IV: The Debt of Tears

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780140443714, 400 pages).

Get the Penguin Classics Hawkes and Minford translation of The Story of the Stone

The Story of the Stone: Or, The Dream of the Red Chamber, Volume IV: The Debt of Tears

Available as an ebook.

Get the Penguin Classics Hawkes and Minford translation of The Story of the Stone

The Story of the Stone: Or, The Dream of the Red Chamber, Volume V: The Dreamer Wakes

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780140443721, 384 pages).

Get the Penguin Classics Hawkes and Minford translation of The Story of the Stone

The Story of the Stone: Or, The Dream of the Red Chamber, Volume V: The Dreamer Wakes

Available as an ebook.

Get the Penguin Classics Hawkes and Minford translation of The Story of the Stone

This small, thin, extract was published in 1996. It was one of a series published to celebrate Penguin’s 60th anniversary.This book is out of print. You may be able to find a used copy for sale online using the links below.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780146001765, 60 pages).

Who is Christine Sun?

Christine Yunn-Yu Sun is a Taiwanese-Australian writer.

» Learn more about Christine Sun on her blog

Sun adapted the other three Classic Chinese novels (The Water Margin, Journey to the West, The Three Kingdoms) for the British company called Real Reads.

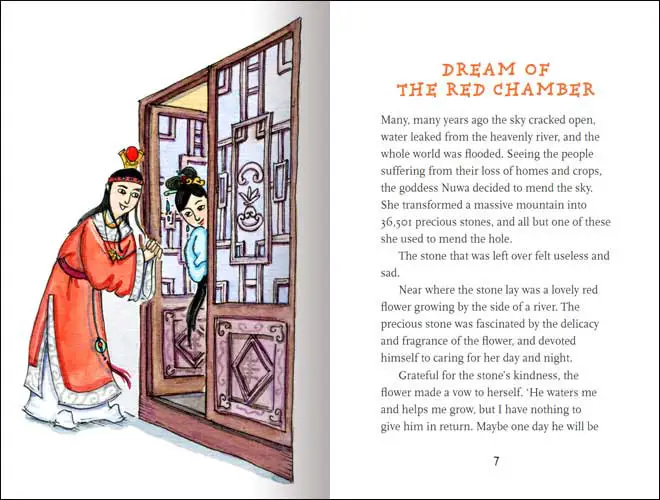

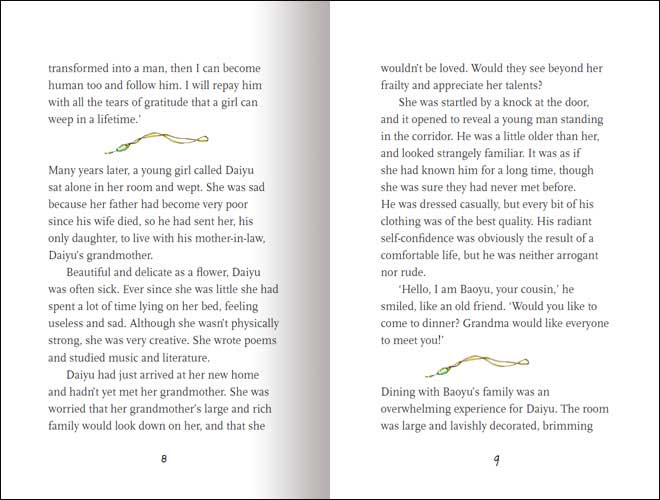

About the Sun adaptation of Dream of the Red Chamber

The illustrations are by Shirley Chiang.

» Learn more about Shirley’s illustrations on her site

There is a teacher’s guide (Scheme of Work) available for download from the publisher.

Extract from the Sun adaptation of Dream of the Red Chamber

Get the Real Reads Sun translation of Dream of the Red Chamber

This short retelling was illustrated by Shirley Chiang.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9781906230364, 64 pages).

Get the Hawkes & Minford translation of The Story of the Stone

Although scholars continue to debate the relative merits of the two complete translations, from what I’ve read, the five-volume Penguin translation is probably the best bet for non-specialists in terms of readability.

Here again are links to Volume 1 of the series to get you started. Enjoy!

Thank you so much for this invaluable study of the relative merits of the various translations. I started with no knowledge whatever and was unaware that most of the books I’d been looking at, sometimes just about to buy, were abridgements or extracts.

I’ve now managed to order the 5 volumes of the Hawkes and Minford translation in used copies for a reasonable price. I totally see the point about possible errors in the exact meaning in this translation. I’ve come across this in translations of other languages, where the translators occasionally fall down in their understanding of subtle meanings in the original. But the extracts you give above made the difference for me. The Hawkes and Minford section was so well put (as an English reading experience) and gave me the impression that deep and rich thought had been put into it. Though the Yang version came across as very good as well, and simpler.

If not for your webpage I probably would have made an idiotic mistake. 🙂

Thanks, KM! I’m so glad to hear the site was useful for you!

In terms of accuracy, Mr. and Mrs. Yangs’ version is far superior.

For example: 想着走入,看时只有一个龙钟老僧在那里煮粥。[雨村见了,便不在意。]及至问他两句话,那老僧既聋且昏,齿落舌钝,所答非所问。

Hawkes & Minford translation: But when he went inside and looked around, he saw only an ancient, wizened monk cooking some gruel [who paid no attention whatsoever to his greetings] and who proved, when Yu-cun went up to him and asked him a few questions, to be both deaf and partially blind. His toothless replies were all but unintelligible, and in any case bore no relation to the questions. : The translators made a mistake here:

The person who paid no attention is not the monk but Yu-cun. 雨村 is the subject of the sentence, not the object. Mr. and Mrs. Yangs’ translation accurately renders this into: Not very impressed, Yutsun casually asked him a few questions.

This is just one example.

Hello! I’d like to start this novel and I’m hesitated about which translated version to read as I’ve read different opinions about which is better. You said that Mr. and Mrs. Yangs’ version is more accurate, so do you suggest that I should read their translation? Thank you!

Have you read the Yangs’ translation? It appears to translate honorifics and titles, and thus represent the subtleties of interpersonal relationships, with far greater precision and nuance than the Hawkes-Minford translation which often ignores or overlooks them. The Dream is all about interpersonal relationships so it’s hard to see how a translation that glosses over the fine aspects of these does the work justic.

Not yet! However, I have bought both the paperback and hardcover versions of the Yangs’ translation and am intending to read it at some point.

I tend to think that different translation choices benefit readers in different contexts, so in that sense there is more than one way to do a text justice.

My experience with the Tyler translation of Tale of Genji was that the authentic details used to convey the characters’ identities were so confusing that they got in the way of me understanding who the characters were. Some simplification improved the clarity in that case.

There is a similar issue in Russian translations… characters are referred to in multiple ways according to their relationships with others, but unless you’re already familiar with the characters or with Russian naming conventions in general, it can be overwhelming.

Do you think the Yangs’ use of honorifics and titles would be confusing to a beginning reader of Chinese classics, or is the wording pretty straightforward?

The vast majority of Western reader who have decided to tackle something so niche as Cao Xueqin are probably aware of the use of honorifics and titles, along with other forms of expressing hierarchical norms, in China. So that’s not really a concern, is it?

As it is, a reader loses much meaning and context of the works themselves if a translator omits the reality of something so important to the culture itself. We can’t really understand why a character becomes so enraged about someone of an inferior status addressing him (or her) in an insulting manner if we don’t understand how the inferior person was supposed to address them in the first place.

As for readability in general for this particular work, I flipped through the Yang and the Hawkes at random points of each, and found that not only do the Yangs address the titles & etc appropriately, but also their samples proved flat-out more readable compared to the Hawkes, which felt too dry and stuffy. Of course, this could be personal preference, but that’s how the readability factors came across to me.

Also, the cheaper alternative, *by far*, is the Yangs translation. Amazon currently has the entire saga as one eBook at $7.99, whereas the Hawkes is five separate ebooks that add up to $70.95. Even as paperbacks, the Yangs version is cheaper than the Hawkes/Penguin.

This is a no-brainer for serious aficionados of East Asian literature, especially those who aren’t swimming in money: Go with the Yangs.

I hear what you’re saying about the honorifics and titles. Thanks for doing a readability comparison and sharing your thoughts!

The ebook you mention that contains the entire saga translated by the Yangs looks… highly suspicious. I doubt it’s produced by a real publisher who has the rights to the translation. If it’s pirated, that would explain not only the low price but also the terrible formatting. Personally, I wouldn’t pay $7.99 for it even if it were legitimate! Since I don’t want to promote a product I’m so unsure about, I’ve left that ebook out of my listing here. I wish the situation were otherwise.

For readers who aren’t swimming in money… Unfortunately the only public domain (legitimately free) translation is the incomplete Joly translation. However, it may be possible to borrow the complete series through a public library system, either in person as physical copies or as ebooks (via an app like Libby).