“Which translation of Noli Me Tangere should I read?”

So you want to read the national novel of the Philippines, often called The Noli, and you don’t read Spanish.

No problem. The work is more often read in English than in the original Spanish.

There are four common, complete English versions of José Pacienza Mercado y Rizal’s 1887 satirical, melodramatic political novel, Noli Me Tángere available from multiple sources. The novel has also been abridged, adapted, bowdlerized, and translated with several different titles, so there’s definitely some potential for confusion. Keep reading to learn how to choose an edition that’s right for you.

If you’re Filipino/a, you’re at least somewhat familiar with Noli Me Tangere because of the 1956 law mandating the study of Rizal’s works. You will have absorbed some information about the plot and characters of Noli Me Tangere, or possibly read the novel in its entirety, but you may not have had a choice about which version to read. If you thought it was boring, it’s well worth giving the novel another try.

From educational publisher Vibal:

With its scathing and humorous attacks on tyranny, hypocrisy and false religion, and its pioneering call to individual virtue and national unity, Noli Me Tangere transcends its political agenda to become a true work of art, thus securing its rightful place in the pantheon of great world literature. It remains as fresh, vivid, moving, and subversive as on the day it was first published.

Noli Me Tangere: Translations

There are four major, complete English translations of Noli Me Tangere, shown below in chronological order.

- 1912 – Charles Derbyshire – The Social Cancer

- 1961 – Leon M. Guerrero – The Lost Eden (Noli Me Tángere)

- 1996 – María Soledad Lacson-Locsin – Noli Me Tángere: A Novel

- 2006 – Harold Augenbraum – Noli Me Tángere (Touch Me Not)

In “The Afterlives of the Noli me tángere” in Philippine Studies vol. 59 no. 4 (2011): 495–527, Anna Melinda Testa-de Ocampo gives a more detailed translation history, listing the following additional editions.

- 1933 – Feliciano Basa and Francisco Benitez, translation with explanatory notes, assisted by Eduardo Montenegro and C. M. Mellen, illus. Juan Luna and Fernando Amorsolo, with an introduction by Manuel L. Quezon. School edition. Manila: Oriental Commercial Co. Inc., 632 pp.

- 1956 – Jorge Bocobo, translation from the original Spanish. Quezon City: R. Martinez and Sons. 488 pp.

- 1957 – Camilo Osias, translation from the Spanish of Dr. Jose Rizal, trans. Camilo Osias. [Manila]: Asian Foundation for Cultural Advancement. 568 pp. 24 cm.

- 1967 – Priscilla Valencia, illus. Adrian Amorsolo. Manila: Phil-Asian Book Co. 404 pp.

- 1989 – Jovita Ventura Castro, translation sponsored by the ASEAN Committee on Culture and Information. Manila: Nalandangan Inc. 388 pp.

Noli Me Tangere: Translation Comparison

Below are details about each of the four major English translations, including extracts for comparison. After that, I’ll share some information on some adaptations, including abridgments, comics, and a graphic novel.

“What is the English meaning of ‘Noli Me Tangere’? Why was this Latin phrase chosen as the title?”

“Noli me tangere” can be translated as “touch me not”. In other words, the meaning of “noli me tangere” in English is “don’t touch me”.

The phrase could have been meant to refer to a flower or a type of cancer, but Rizal said it was a quote from the Bible.

This article in the Manila Times points out that Rizal said that the quote was from the Gospel of Luke when it is actually from the Gospel of John, and elaborates on the connection to cancer.

The author’s dedication to his fatherland is reproduced in the Derbyshire translation, which is titled The Social Cancer. The dedication draws a comparison between the ills of society and the ills of a human body suffering from a particularly painful form of cancer:

Recorded in the history of human sufferings is a cancer of so malignant a character that the least touch irritates it and awakens in it the sharpest pains. Thus, how many times… hath thy dear image presented itself showing a social cancer like to that other!

From Charles Derbyshire’s introduction:

Noli Me Tangere (“Touch Me Not”) at the time the work was written had a peculiar fitness as a title. Not only was there an apt suggestion of a comparison with the common flower of that name, but the term is also applied in pathology to a malignant cancer which affects every bone and tissue in the body, and that this latter was in the author’s mind would appear from the dedication and from the summing-up of the Philippine situation in the final conversation between Ibarra and Elias. But in a letter written to a friend in Paris at the time, the author himself says that it was taken from the Gospel scene where the risen Savior appears to the Magdalene, to whom He addresses these words, a scene that has been the subject of several notable paintings.

In this connection it is interesting to note what he himself thought of the work, and his frank statement of what he had tried to accomplish, made just as he was publishing it: “Noli Me Tangere, an expression taken from the Gospel of St. Luke, means touch me not. The book contains things of which no one up to the present time has spoken, for they are so sensitive that they have never suffered themselves to be touched by any one whomsoever.”

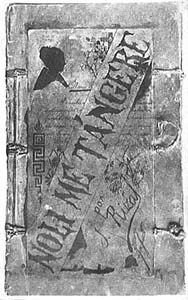

About the original cover of Noli Me Tangere

The original cover of Noli Me Tangere shows a variety of symbols: a silhouette of a woman, a cross, some plants, a torch,a pair of legs, a helmet, and instruments of punishment. In addition to the title and author’s name, there is a dedication which does not appear elsewhere, written by the author to his parents.

The original cover has been adapted or incorporated into the covers for the editions published by Guerrero, Dover, Bookmark, and Penguin.

“Who Was Charles E. Derbyshire?”

He was an American translator with a pro-American bias and an anti-clerical bias.

It suited him to translate a novel that was critical of the Spanish colonial government, as he was American, and when his translation was published, American rule over the Philippines had begun over a decade earlier, in 1898. According to Derbyshire, Spanish rule over the Philippines was initially beneficial to the local people, but had become corrupted to such an extent that its overthrow was inevitable.

Notwithstanding the “noble aims” of the friar orders, Derbyshire saw their entrenchment as a barrier not just to prosperity but also to moral and intellectual progress:

“[I]f there be any fact well established in human experience it is that with economic development the power of organized religion begins to wane—the rise of the merchant spells the decline of the priest. A sordid change, from masses and mysteries to sugar and shoes, this is often said to be, but it should be noted that the epochs of greatest economic activity have been those during which the generality of mankind have lived fuller and freer lives, and above all that in such eras the finest intellects and the grandest souls have been developed.” [emphasis added]

About the Derbyshire translation of Noli Me Tangere

- It is cheap or free because it is no longer under copyright.

- The text is considered a faithful translation in terms of style and content.

- It is missing the chapter, “Elias and Salome”, which was deleted from the draft by the author before the book’s initial publication for financial reasons.

- The reading may be rough going because the language is old-fashioned and the text contains untranslated Spanish and local words, quotations in other foreign languages, unexplained cultural practices, and literary references.

As far as I know, The Social Cancer is not printed and sold as a paperback by any major publisher. However, since its copyright has expired, you can get a legitimate ebook online for free. See below.

Extract from the Derbyshire translation of Noli Me Tangere

Get the Project Gutenberg Derbyshire translation of The Social Cancer

Includes a 50-page introduction by the translator; the author’s dedication; notes at the end of each chapter; a glossary.

Available as an ebook.

“Who was Leon Ma. Guerrero?”

A Filipino nationalist, lawyer, journalist and diplomat, he is also known as “Leon M. Guerrero III” or “León María Ignacio Agapito Guerrero y Francisco” or just LMG. He wrote the prizewinning biography of José Rizal, The First Filipino.

About the Guerrero translation of Noli Me Tangere

- It is a highly accessible modern paraphrase with explanations incorporated into the text. In fact, it was subtitled “A Completely New Translation for Contemporary Readers”.

- Paraphrase can be jarring. Guerrero used language that does not fit the time and place the book describes. For example, he tried to portray the difference in the styles of Spanish using anachronistic Filipino English and an Old South dialect of American English.

- Parts of the text are deliberately distorted. Guerrero’s version is said to be preferred by Catholic schools in the Philippines because he supposedly removed “objectionable” content. The late scholar Benedict Anderson, in his 1997 London Review of Books article about the Lacson-Locsin translation, says:

[The Guerrero translation is] fatally flawed by systematic bowdlerisation in the name of official nationalism. Sex, anticlericalism and any perceived relevance to the contemporary nation are all relentlessly excised, with the aim of turning Rizal into a boring, long-dead national saint.

It’s hard to imagine how a book written to expose abuses of power could be translated in such a way as to hide them, though, and I can’t find any specific examples. For example, in Chapter 25 of both the Derbyshire and Guerrero versions, Padre Salvi is a peeping Tom.

Extract from the Guerrero translation of Noli Me Tangere

Get the Dover Guerrero translation of The Lost Eden

This is a republication of the work published by Indiana University Press in 1961. Includes a new introductory note specially prepared for this edition. Includes an introduction by the translator.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780486834429, 384 pages).

Get the Dover Guerrero translation of The Lost Eden

This is a republication of the work published by Indiana University Press in 1961. Includes a new introductory note specially prepared for this edition. Includes an introduction by the translator.

Available as an ebook.

Get the Anvil Guerrero translation of The Lost Eden

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9789712735035, 368 pages).

“Who was María Soledad Lacson-Locsin?”

María Soledad Lacson (viuda de Locsín) was a Filipina educated in both Spanish and English who came from a family of writers and publishers. Her son Raul L. Lacson edited her translation after her death.

About the Lacson-Locsin translation of Noli Me Tangere

It was the first to be retranslated from “from facsimile editions of the manuscripts and to restore significant sections of the original text,” which, according to the publisher, made it “the most authoritative and faithful English translation to date.”

It contains the deleted/restored chapter “Elias and Salome”, which is slotted in as Chapter 25.

Extract from the Lacson-Locsin translation of Noli Me Tangere

Get the University of Hawaii Lacson-Locsin translation of Noli Me Tangere

Edited by Raul L. Locsin. Part of the SHAPS Library of Translations series. Contains endnotes.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780824819170, 472 pages).

“Who is Harold Augenbraum?”

He is an American writer, editor, and translator. As of 2019, he is the associate director of the Yale Translation Initiative. He first heard of Rizal when reading the work of an author he assumed was Latino but who was actually Filipino.

Noli Me Tangere was the first Filipino work to be published by Penguin Classics. Augenbraum’s translation of the sequel, El Filibusterismo, was published subsequently when The Noli encountered encouraging success. There are now five Filipino Penguin Classics. Filipina Elda Rotor wants to add more to the list for the benefit of both the general reader and students in university literature courses.

About the Augenbraum translation of Noli Me Tangere

The introduction helps place the novel in its historical context by describing the life and fate of the author and explaining his place in the history of Spanish colonialism in Asia as the “historical ‘guiding saint’ of the Philippine revolution”. Don’t read the introduction before you read the novel, though. The introduction gives away the novel’s ending!

This edition contains the deleted / restored chapter “Elias and Salome” as an appendix.

Extract from the Augenbraum translation of Noli Me Tangere

Get the Penguin Classics Augenbraum translation of Noli Me Tangere / Touch Me Not

Includes an introduction and endnotes by Harold Augenbraum. Includes an author bio, a note on the translation, and suggestions for further reading.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9780143039693, 484 pages).

Get the Penguin Classics Augenbraum translation of Noli Me Tangere / Touch Me Not

Includes an introduction and endnotes by Harold Augenbraum. Includes an author bio, a note on the translation, and suggestions for further reading.

Available as an ebook (ISBN 9781440649370).

Guides for Noli Me Tangere

LitCharts literature guide for Noli Me Tangere

GradeSaver study guide for Noli Me Tangere

Penguin Reader’s Guide for Noli Me Tangere

Get An Eagle Flight (adaptation of Noli Me Tangere from 1900) by José Rizal

The first English translation of The Noli is said to be based on the French translation published in the previous year. The unidentified translator seems to have changed the title in order to praise Rizal’s purity of purpose by likening him to an eagle who was flying, in the words of Shakespeare, “bold and forth on”. The eagle may also have been chosen to appeal to the translation’s American target audience. Some chapters were omitted and the rest were shortened.

Available as an ebook.

Get Friars and Filipinos (abridged translation of Noli Me Tangere from 1902) by José Rizal

Frank Ernest Gannet translated The Noli while serving as the secretary to the head of a group sent to the Philippines gather information for the US government to use to decide how to govern the colony. The purpose of the translation was to highlight problems caused by corrupt friars. He omitted sixteen of the original sixty-four chapters.

Available as an ebook.

Get The Graphic Novel adaptation of Noli Me Tangere (2016) by Leo Miranda and D.G. Dumaraos

Illustrated by Ibarra Cruz Crisostomo and Leonardo Giron.

Available as a paperback (ISBN 9786214200610, 52 pages).

Get The Graphic Novel adaptation of Noli Me Tangere (2016) by Leo Miranda and D.G. Dumaraos

Illustrated by Ibarra Cruz Crisostomo and Leonardo Giron.

Available as an ebook (ISBN 9786214201310).

Noli Me Tangere: Best Translation

Created for a global audience, the Penguin Augenbraum translation of Noli Me Tangere strikes a good balance between accuracy and accessibility.